[Herald Review] Jeju director’s film features 1948 Jeju Massacre

By Claire LeePublished : Oct. 10, 2012 - 19:37

O Muel’s ‘Jiseul’ portrays tragic historical event in exquisite black-and-white cinematography

BUSAN -- Director O Muel occupies a rare place in Korean cinema, being one of the very few filmmakers creating works about Jeju Island. All of his previous films were shot on his native Jeju, in Jeju dialect, featuring the lives of people living on the island.

Two previous films, “Pong Ddol” (2010) and “Nostalgia” (2009) were rather humorous accounts of ordinary Jeju residents, from a flakey filmmaker to a middle-aged man who wants to learn how to play guitar. The films depict the unique community culture of the people of Jeju, as well as their distinctive folk customs.

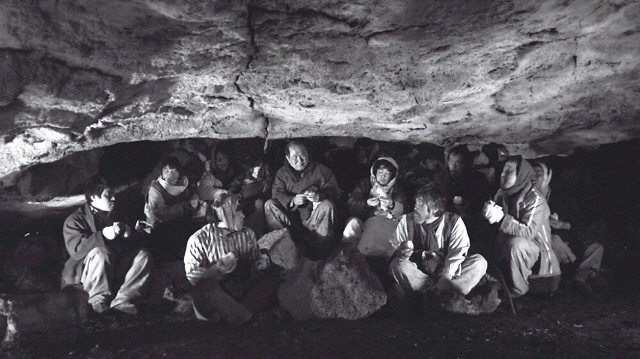

O’s latest film “Jiseul,” however, is an artful, grim piece about a horrific historical event on the island. Unveiled to the press on Sunday as part of the Busan International Film Festival, it tells the story of a group of some 120 villagers who hid from soldiers in a cave during the 1948 Jeju Massacre. The historical event resulted in the death of some 30,000 islanders as the government sought to quell an uprising led by a small group of communist insurgents.

BUSAN -- Director O Muel occupies a rare place in Korean cinema, being one of the very few filmmakers creating works about Jeju Island. All of his previous films were shot on his native Jeju, in Jeju dialect, featuring the lives of people living on the island.

Two previous films, “Pong Ddol” (2010) and “Nostalgia” (2009) were rather humorous accounts of ordinary Jeju residents, from a flakey filmmaker to a middle-aged man who wants to learn how to play guitar. The films depict the unique community culture of the people of Jeju, as well as their distinctive folk customs.

O’s latest film “Jiseul,” however, is an artful, grim piece about a horrific historical event on the island. Unveiled to the press on Sunday as part of the Busan International Film Festival, it tells the story of a group of some 120 villagers who hid from soldiers in a cave during the 1948 Jeju Massacre. The historical event resulted in the death of some 30,000 islanders as the government sought to quell an uprising led by a small group of communist insurgents.

O, who was born and grew up on Jeju, majored in Korean painting at Cheju National University and later worked in Jeju’s performing arts scene by founding a local theater troupe. His background in fine art, as well as his Jeju upbringing, is evident throughout the film. Filmed in black and white, every single shot is exquisitely framed and precisely envisioned. All of the Jeju villagers in the film speak in their native dialect, which is translated in subtitles provided in standard Korean.

The film is divided into four parts: sinwi, sinmyo, eumbok and soji. The terms come from Korea’s ancestral rites. Sinwi means to invite the spirits. Sinmyo refers to a place where the invited spirits stay during the ceremony, while eumbok means to share the ritual food. Soji, finally, is the burning of paper envelopes on which the names of the spirits are written. In the end, the film is O’s own memorial service for the victims, in the form of cinema.

Almost 80 percent of the film dwells on how the villagers spend their time in and out of the cave, in their efforts to escape the soldiers -- who were ordered by Seoul to kill everyone living beyond 5 km from the coast.

They are simple, mostly good-hearted people, who don’t have a real grasp of what’s going on. One of them worries about his pigs left behind at home, insisting he must go back to his town to feed them. Some of the people are hopelessly optimistic, saying they’d be out of their cage in the next week or two.

As they spend their nights together in their dark sanctuary, the villagers, all in their Jeju dialect, talk about random things, make fun of each other, share limited food, and eventually go to sleep. Young men talk about the women they like, while older men talk about mating their pigs.

In O’s film, the soldiers are also portrayed as victims. The young men don’t understand their mission and are extremely afraid to kill the innocent. Their sense of guilt, as well as their brutal violence, is shown with powerful images of bodies of dead pigs, as well as a young woman raped and murdered. O overlaps the contour of her naked body with Jeju’s oreums -- volcanic cones that look like small mountains or hills -- which create an intense, poetic imagery, connecting the horrific historical event with Jeju’s nature.

The film’s title “Jiseul” refers to potatoes in Jeju dialect. They are the only food the villagers have to eat in the film. While the dead pigs symbolize violence, the potatoes reflect hope and solidarity. The villagers never get into food fights while living in the cave. They are grateful for the potatoes, and many give them up for others to have more.

After the screen goes black, what one remembers the most is the rather silly conversation of the simple villagers and their friendships, in spite of their tragic end that they never foresaw or understood.

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)