Financial regulators and creditor banks here have been picking up the pace toward restructuring an increasing number of unprofitable companies saddled with heavy debts.

Earlier this month, the country’s financial watchdog announced a list of 175 small and medium enterprises to be subject to workout programs or closed down. About 200 underperforming large firms are now undergoing the final phase of credit risk assessments by their major lenders.

Government officials have prodded local banks and other financial institutions to hasten the work to sift through debt-ridden and unprofitable companies that should not be allowed to stay afloat. Behind their push is a sense of urgency that time is running short of preventing Korea’s economy from being jolted by the sudden collapse of failing companies, which might be prompted by increasingly unfavorable conditions at home and abroad.

“Many heavily indebted companies in the country may no longer manage to keep themselves afloat if borrowing costs get higher in parallel with U.S. interest rate hikes that are likely to start next month,” said an official at the Ministry of Strategy and Finance, asking not to be named.

In a recent meeting with other economic policymakers, Finance Minister Choi Kyung-hwan reiterated the need to expedite corporate restructuring. Emphasizing the importance of a “preemptive response,” he said all policy efforts should be made to push for restructuring work in a swift manner based on strict assessment.

The top economic officials decided to complete the credit risk assessment of large companies within the year and set up an interministerial consultative body to take over the work to overhaul shipbuilding, shipping, steelmaking and other sectors sensitive to business cycles from creditor banks. The country’s three big shipbuilders, which have been hit hard by order cancellations amid the slump in global trade, are forecast to record a combined operating loss of 7.8 trillion won ($6.8 billion) this year, marking the first time they have suffered losses on an annual basis.

Critics note the delay in corporate restructuring has inflated the problem involving failed businesses into a major risk factor for the Korean economy.

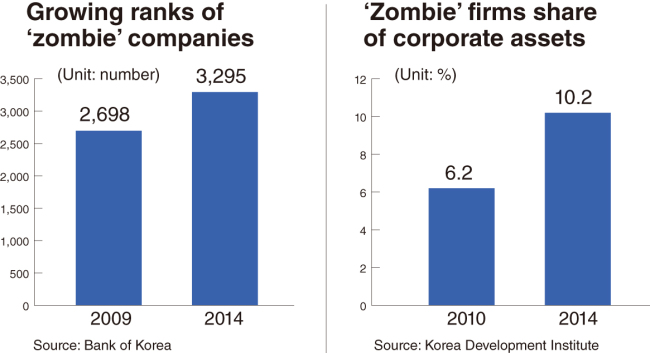

Of the 1,684 listed companies, 234 have failed to generate enough profits to pay interest on their debts for three consecutive years. If unlisted firms are included, the number of zombie companies exceeds 3,200, according to data released by the Bank of Korea early this month.

The Korea Development Institute, a state-funded think tank, indicated in its recent report that government-run banks, in particular, have been slower and less efficient in pushing for corporate restructuring.

“Most specialized banks were found to have increased loans to underperforming companies in severe financial distress, resulting in delaying the start of their workout programs,” said Nam Chang-woo, a researcher at the institute.

The KDI report showed the assets held by insolvent businesses accounted for 10.2 percent of the total corporate properties last year, up from 6.2 percent in 2010.

Some economists, however, caution that an overemphasis on the swift implementation of restructuring may spread fears that all industries are in a dangerous situation.

“The current economic team needs to take a more balanced and sophisticated approach to avoid sending unnecessarily negative signals to the market,” said Yoon Suk-heun, professor of finance at Soongsil University in Seoul.

Analysts also note the hasty restructuring process may force some companies that can become viable over the long term to be shut down. They say these companies should be given a minimum period of time to make self-help efforts.

Yoon warned of the possibility that what may be seen as an unfair approach to large and small firms will prompt resistance to the restructuring work as a whole, which he sees as essential for containing any fallout from worsening external and internal risks on the country’s economy and solidifying its growth potential.

In this regard, many economists say, corporate restructuring needs transparency and objectivity as well as swiftness, with sights set on restoring and improving the global competitiveness of local companies. It would be unwise to let the immediate need to improve corporate financial status hurt long-term efforts to develop new growth engines needed to buttress the Korean economy in the future, they argue.

Yoon said a persistent channel of dialogue needs to be maintained among government agencies, creditor banks and business circles to ensure that corporate restructuring will be implemented in a more efficient and relevant manner.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] No more 'Michael' at Kakao Games](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050183_0.jpg&u=20240428180321)