[Kim Myong-sik] Small opening in North Korean aid blockage

By Korea HeraldPublished : April 15, 2015 - 19:41

“I often felt that we were in some kind of ‘collusion’ with them,” said the Korean-American medical doctor who works for the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology in the North Korean capital. “We” in his remarks are he and other expatriate faculty members at the institute established with donations mainly from South Korea, and “them” are the young North Korean students at PUST.

Dr. Moses Kang was speaking at a seminar on helping the North in the area of public health held at Seoul’s Somang Presbyterian Church earlier this month. The quarterly event hosted by the One Peninsula Medical Union was attended by PUST president Kim Jin-kyung and other faculty members visiting Seoul, refugees from the North in the medical profession and people “with compassion for the North Korean people.”

Dr. Moses Kang was speaking at a seminar on helping the North in the area of public health held at Seoul’s Somang Presbyterian Church earlier this month. The quarterly event hosted by the One Peninsula Medical Union was attended by PUST president Kim Jin-kyung and other faculty members visiting Seoul, refugees from the North in the medical profession and people “with compassion for the North Korean people.”

Kang used the Korean word “gongmo,” which is best translated as collusion in English, but what he actually meant was “tacit understanding.” He tried to explain how the students and their teachers from outside the country have built trust in each other through years of interactions that eventually opened their hearts. Sitting at the seminar as a plain observer, I envisioned emotional chemistry being fomented between them in classrooms and laboratories where only English is spoken.

PUST is a unique institute, to say the least. It opened undergraduate and graduate courses in 2010 after nearly 10 years of bumpy preparations with financial contributions from Christian churches in South Korea and the United States. Four hundred students have been recruited from the elite society of the North and first MAs were produced in May last year and first BAs in October. Five medical departments are planned to be added to PUST, according to its president.

The idea of creating a research university in the North Korean capital with South Korean money met sharply divided reactions when it was conceived during the years of Kim Dae-jung’s liberal rule here. Its key promoters, Kim Jin-kyung, an immigrant to the U.S. with academic and business backgrounds, and Rev. Kwak Sun-hee, the founding pastor of the Somang Church, were praised by many Christians as crusaders for North Korean evangelization while skeptics warned of squandering money in vain hope.

Yet, the project progressed notwithstanding the sliding of ties between the two Koreas with the North’s nuclear and rocket tests and the sinking of the patrol craft Cheonan. As actual teaching began on the campus in Pyongyang suburbs by more than 200 instructors from South Korea, the U.S. and Canada, conservative activists here protested that the institute for advanced technologies was serving as a major training facility for hackers targeting South Korea.

Students exposed to the capitalist method of teaching by those “foreign” instructors are accommodated in dormitories almost entirely provided with capitalist supplies. So, it is not hard to imagine the inevitable “detox” process in that indoctrinated society. Under these circumstances, the relations between the givers and receivers of knowledge at PUST should be different from those at other places of education.

The medical professor from Pyongyang produced slides of his students in their first, second and third years and upon graduation. Those sitting in the freshman class, all wearing white shirts and colored ties, diffused an air of rigidity in their expressions and postures. Pictures taken in the following years showed increasing signs of relaxation, and those of the graduating class were laughing mischievously just as their counterparts here in the South do, except for the uniforms and absence of girls. Kim Jin-kyung said 10 female students were admitted this year for the first time.

The seminar went on to discuss the dire public health situation in the North that calls for immediate shipment of medicine and medical equipment, aside from the long-term program of supporting PUST, the only private educational institute in the DPRK. One strongly recommended aid item, according to the doctors from Pyongyang, was solar power generator kits to be installed at North Korean hospitals.

Dr. Kang asked the audience to imagine a power outage during an abdominal operation, which is not unusual in the North. Lee Hye-gyeong, who took refuge in the South in 2002 after serving as a pharmacist in Pyongyang, gave the vivid description of the worsening medical supplies situation while she was in the North. “They used to deliver medicine to my hospital with a 2.5-ton truck. During the ‘arduous march’ (in the 1990s), this was reduced to a 25 kg sack each time,” she said.

Lee is a strong woman who passed the exam for a pharmacist’s license while living here with her two children. It was shocking to hear that she had supplemented her income by selling her blood to patients at the North Korean hospital and that other staffers were doing the same. Only those who could afford to obtain medicine from the unofficial market and buy blood from whichever donors they could find received treatment at her hospital. “Others who could not do so remain home and die in the socialist state guaranteeing totally free medical services,” she said.

Three million died during the “arduous march,” one half from starvation and the other half from diseases caused by malnutrition. Prevalent were tuberculosis (with 140,000 sufferers or 6 percent of the total population), cholera, typhoid fever and venereal disease. Since the authorities ordered hospitals not to turn away patients without treatment, they could only provide the traditional “Koryo medicine,” which did not require Western drugs. This information was, of course, not new, but it was appalling to hear it from one who lived through the severity.

The four-hour seminar in a basement hall at my church in that afternoon was an eye-opening experience. Even one of the presenters surprisingly argued that providing the North with consumer medicines could rather aggravate what he called the “polarization” of public health because they just end up in the hands of the rich and powerful. The doctors agreed on the need for the supply of durable, advanced equipment such as celioscopes, which could save many lives.

Five years after the Cheonan incident, the subsequent May 24, 2010, measures are still in force with a general embargo on material aid to the North. The sight of the obese young North Korean leader swaggering through attack military units on TV is a strong discourager of assistance to the North. Yet, the little seminar reconfirmed that humanitarianism should go beyond that.

By Kim Myong-sik

Kim Myong-sik is a former editorial writer for The Korea Herald. ― Ed.

Dr. Moses Kang was speaking at a seminar on helping the North in the area of public health held at Seoul’s Somang Presbyterian Church earlier this month. The quarterly event hosted by the One Peninsula Medical Union was attended by PUST president Kim Jin-kyung and other faculty members visiting Seoul, refugees from the North in the medical profession and people “with compassion for the North Korean people.”

Dr. Moses Kang was speaking at a seminar on helping the North in the area of public health held at Seoul’s Somang Presbyterian Church earlier this month. The quarterly event hosted by the One Peninsula Medical Union was attended by PUST president Kim Jin-kyung and other faculty members visiting Seoul, refugees from the North in the medical profession and people “with compassion for the North Korean people.” Kang used the Korean word “gongmo,” which is best translated as collusion in English, but what he actually meant was “tacit understanding.” He tried to explain how the students and their teachers from outside the country have built trust in each other through years of interactions that eventually opened their hearts. Sitting at the seminar as a plain observer, I envisioned emotional chemistry being fomented between them in classrooms and laboratories where only English is spoken.

PUST is a unique institute, to say the least. It opened undergraduate and graduate courses in 2010 after nearly 10 years of bumpy preparations with financial contributions from Christian churches in South Korea and the United States. Four hundred students have been recruited from the elite society of the North and first MAs were produced in May last year and first BAs in October. Five medical departments are planned to be added to PUST, according to its president.

The idea of creating a research university in the North Korean capital with South Korean money met sharply divided reactions when it was conceived during the years of Kim Dae-jung’s liberal rule here. Its key promoters, Kim Jin-kyung, an immigrant to the U.S. with academic and business backgrounds, and Rev. Kwak Sun-hee, the founding pastor of the Somang Church, were praised by many Christians as crusaders for North Korean evangelization while skeptics warned of squandering money in vain hope.

Yet, the project progressed notwithstanding the sliding of ties between the two Koreas with the North’s nuclear and rocket tests and the sinking of the patrol craft Cheonan. As actual teaching began on the campus in Pyongyang suburbs by more than 200 instructors from South Korea, the U.S. and Canada, conservative activists here protested that the institute for advanced technologies was serving as a major training facility for hackers targeting South Korea.

Students exposed to the capitalist method of teaching by those “foreign” instructors are accommodated in dormitories almost entirely provided with capitalist supplies. So, it is not hard to imagine the inevitable “detox” process in that indoctrinated society. Under these circumstances, the relations between the givers and receivers of knowledge at PUST should be different from those at other places of education.

The medical professor from Pyongyang produced slides of his students in their first, second and third years and upon graduation. Those sitting in the freshman class, all wearing white shirts and colored ties, diffused an air of rigidity in their expressions and postures. Pictures taken in the following years showed increasing signs of relaxation, and those of the graduating class were laughing mischievously just as their counterparts here in the South do, except for the uniforms and absence of girls. Kim Jin-kyung said 10 female students were admitted this year for the first time.

The seminar went on to discuss the dire public health situation in the North that calls for immediate shipment of medicine and medical equipment, aside from the long-term program of supporting PUST, the only private educational institute in the DPRK. One strongly recommended aid item, according to the doctors from Pyongyang, was solar power generator kits to be installed at North Korean hospitals.

Dr. Kang asked the audience to imagine a power outage during an abdominal operation, which is not unusual in the North. Lee Hye-gyeong, who took refuge in the South in 2002 after serving as a pharmacist in Pyongyang, gave the vivid description of the worsening medical supplies situation while she was in the North. “They used to deliver medicine to my hospital with a 2.5-ton truck. During the ‘arduous march’ (in the 1990s), this was reduced to a 25 kg sack each time,” she said.

Lee is a strong woman who passed the exam for a pharmacist’s license while living here with her two children. It was shocking to hear that she had supplemented her income by selling her blood to patients at the North Korean hospital and that other staffers were doing the same. Only those who could afford to obtain medicine from the unofficial market and buy blood from whichever donors they could find received treatment at her hospital. “Others who could not do so remain home and die in the socialist state guaranteeing totally free medical services,” she said.

Three million died during the “arduous march,” one half from starvation and the other half from diseases caused by malnutrition. Prevalent were tuberculosis (with 140,000 sufferers or 6 percent of the total population), cholera, typhoid fever and venereal disease. Since the authorities ordered hospitals not to turn away patients without treatment, they could only provide the traditional “Koryo medicine,” which did not require Western drugs. This information was, of course, not new, but it was appalling to hear it from one who lived through the severity.

The four-hour seminar in a basement hall at my church in that afternoon was an eye-opening experience. Even one of the presenters surprisingly argued that providing the North with consumer medicines could rather aggravate what he called the “polarization” of public health because they just end up in the hands of the rich and powerful. The doctors agreed on the need for the supply of durable, advanced equipment such as celioscopes, which could save many lives.

Five years after the Cheonan incident, the subsequent May 24, 2010, measures are still in force with a general embargo on material aid to the North. The sight of the obese young North Korean leader swaggering through attack military units on TV is a strong discourager of assistance to the North. Yet, the little seminar reconfirmed that humanitarianism should go beyond that.

By Kim Myong-sik

Kim Myong-sik is a former editorial writer for The Korea Herald. ― Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Grace Kao] Hybe vs. Ador: Inspiration, imitation and plagiarism](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050220_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Mom’s Touch seeks to replicate success in Japan](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050568_0.jpg&u=)

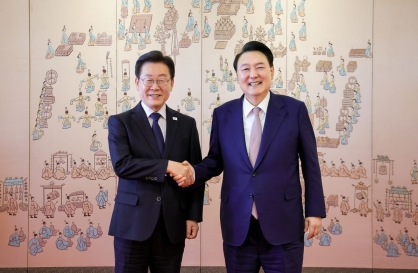

![[News Focus] Lee tells Yoon that he has governed without political dialogue](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050696_0.jpg&u=20240429210658)

![[Today’s K-pop] Seventeen sets sales record with best-of album](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/30/20240430050818_0.jpg&u=)