After 70 years of turbulent transition, South Korea’s democracy faces new challenges

By 옥현주Published : Aug. 16, 2015 - 18:38

In the chaotic decades that followed the 1945 liberation from Japan’s colonial rule, South Koreans had limited rights to pick their own leaders, express political beliefs, and participate in any form of policymaking.

They lived under the constant threat of oppressive, militant rulers who were desperate to remain in power in the name of economic development and fighting communism.

It was perhaps the state’s strong power that transformed South Korea into a powerful economy for the years to come, but it was the people who established the value of free democracy through decades of struggles and sacrifices.

Through this dramatic history of citizens’ unrelenting quest for freedom, the procedural democracy that guarantees the people’s equal right to pick their own leaders was fully established.

According to the annual democracy index released by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2014, South Korea is now considered a “full democracy,” along with only 24 other countries out of 167 nations.

They lived under the constant threat of oppressive, militant rulers who were desperate to remain in power in the name of economic development and fighting communism.

It was perhaps the state’s strong power that transformed South Korea into a powerful economy for the years to come, but it was the people who established the value of free democracy through decades of struggles and sacrifices.

Through this dramatic history of citizens’ unrelenting quest for freedom, the procedural democracy that guarantees the people’s equal right to pick their own leaders was fully established.

According to the annual democracy index released by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2014, South Korea is now considered a “full democracy,” along with only 24 other countries out of 167 nations.

However, the nation today has come to face a series of new challenges, with progressive critics and scholars voicing concerns that the country’s democracy is in retreat, as the country travels from the whirlwind era of democratic movements, through the progressive governments, and on to conservative leadership.

Questions are growing over the qualitative aspects of the nation’s democracy on how well the power delegated by the people is being exercised. Debate has also been going on for years over how to revise the Constitution to distribute Korea’s imperialistic presidential power and expand people’s participation in policy development.

The discussion began to accelerate upon the launch of the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration in 2008, over whether the government’s seemingly increasing social and political intervention was a regressing democracy or pursuit of order and defense against constant North Korean threats. Meanwhile, the country continued to struggle to find a balance on how much the state should intervene in the economy since the 1997 financial crisis.

Public angst over the administration grew during the nationwide candlelight vigils against reintroduction of U.S. beef imports in 2008, the Yongsan tragedy of 2009, where six people were killed in a clash between redevelopment protesters and riot police, and the passage of media law revision in 2009 that effectively gave broadcasting licenses to major conservative papers.

Other incidents followed in the next conservative Park Geun-hye administration including the National Intelligence Service’s alleged interference in the presidential campaign in 2012, and the unprecedented dissolution of the ultraleft Unified Progressive Party in 2014 for being pro-North and seeking to overthrow the government.

Most recently, the unresolved problems of South Korean democracy were laid bare when Rep. Yoo Seong-min, then floor leader of the ruling Saenuri Party was forced out of his party position after remarks by President Park, who accused him of betraying and hindering the government’s key policies. The NIS, the key organization behind the administration’s anti-North security, has again been placed in the political hot seat with civilian hacking allegations.

Fight for democracy

After liberation from Japan’s colonial rule in 1945, Korea went through national division, a fratricidal war and decades of dictatorship. People resisted, risking their lives and shedding their blood, to bring dictators to their knees.

To understand South Korea’s democracy movement, it’s important to look into the political context that motivated the authoritarian government, said Paul Chang, assistant professor of sociology at Harvard University.

“A fundamental characteristic of the repressive governments in the 1970s and 1980s was the reliance on the anti-communist ideology to justify the repression of civil and political dissent,” Chang said in an email interview.

“The democracy movement and the authoritarian government were locked in a contest to define what South Korean politics and society should be, all within the larger context of the Cold War that loomed over the country’s history since the division in 1948 and the civil war in 1950,” he said.

In 1960, students, teachers and intellectuals led a wave of protests to oust Syngman Rhee, the country’s first president, who stayed in power for nearly 12 years. Rhee sought constitutional amendment twice to stay in power indefinitely. Students took to the streets on April 19 to protest against him as he attempted to continue his grip on power through election fraud. Amid mounting public pressure, Rhee resigned and exiled himself to Hawaii, where he died five years later.

After Rhee, military elites seized power, through a coup d’etat. On May 16, 1961, Maj. Gen. Park Chung-hee established a military junta and tightened state control, using draconian emergency decrees. In 1972, he declared the Yushin Constitution that gave him a dictatorial power as he was able to extend his presidency without seeking reelection. Anti-Yushin campaigns continued throughout the 1970s despite the government’s harsh oppression of Park’s political opponents, student activists and other civilians suspected of opposing him. Until he was assassinated by his spy agency chief in late 1979, Park’s opponents were held without trial and tortured, with numerous cases of unexplained deaths.

After Park’s demise, hopes for democracy spread, but were soon quelled by another coup led by Army Gen. Chun Doo-hwan.

Then on May 18, 1980, Gwangju citizens rose up against him as he tried to consolidate his power by expanding martial law. More than 200 people died in the bloody crackdown by the military, but the incident was concealed by his government and its strong control of the media.

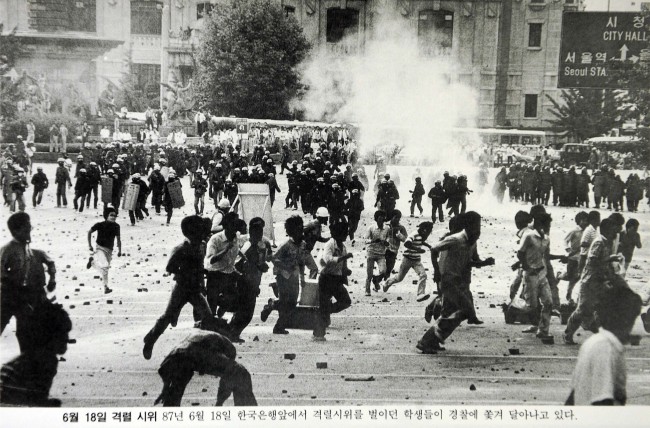

The Gwangju Popular Uprising, however, eventually led to another mass-democratization movement in 1987. A broader range of people, in cooperation with opposition leaders, held rallies, demanding a return to a direct election system. After several days of protest, the ruling camp, including Chun’s chosen heir Roh Tae-woo, promised that the government would accept popular presidential elections and restore political rights to Kim Dae-jung, the opposition politician, who later became the president a decade later.

Between 1987 and 2015, Korea went through five presidential elections, which included two sets of peaceful transition from the ruling party to the opposition.

“The 1987 constitutional revision normalized the constitutional system and thus arbitrary abuses of state powers were considerably reduced,” wrote Lee Myung-sik in his 2010 book titled “The History of Democratization Movement in Korea.”

The system brought stability in electoral democracy, but played a limited role in improving the quality of the lives and distribution of power, he said.

“Progress in political democracy has failed to spill over to socioeconomic democracy. Instead, wealth and privilege has become concentrated in a few upper echelons of society,” he said. “Inter-Korean tension and regional antagonism also remain unresolved.”

New challenges

Now, calls are growing to amend the 1987 political system to better reflect the changing situation, as society struggles with a polarization of views between the progressives and the conservatives.

“Probably the most significant impediment for further consolidating democracy is the polarization of South Korean society and politics. ... Through the crucible of state repression the ideology and identity of progressive forces became entrenched. And because of this, there is very little constructive dialogue between conservative and progressive forces in Korean society and politics,” pointed Chang of Harvard University.

“It’s easy to forget that a healthy democracy does not mean that we always get our way. Rather, a mature democracy can accept oppositional leadership and policies, even if we do not agree with them, as long as they reflect the majority will of the people and the rule of law,” he went on, saying that dialogue and mutual respect are necessary between progressives and conservatives.

Systematically, the political structure that has remained unchanged since 1987 requires change, other experts noted.

“The goal of the 1987 political system was to have the power watched by the people, prevent someone from seeking more than one-term and to establish procedural democracy,” said Kang Won-taek, political professor at Seoul National University, in an interview published by Shin DongA.

Kang suggested opening a discussion on constitutional amendments to change the presidential system to a parliamentary system to have the group of leaders more responsible politically.

A single-term presidency has resulted in discontinuity of major long-term policies, and the current system is insufficient to determine the political ability of candidates running for the presidency, he said.

On mounting calls for political reform, Yoon Seong-yi, a political professor at Kyung Hee University, focuses on a paradigm shift from a growth-driven industrial society to a digital era. It has made not only the people change their everyday behavior but also their political beliefs, he said.

Recent talk of open primaries reflects the people’s growing opposition to unilateral decisions made by leaders and also their desire to decentralize power.

“The people today no longer remains obedient to the state. They want to their voices heard and reflect their ideas on policymaking by directly communicating with their representatives through digital platforms,” he said.

Calls for political reform and fairer distribution of power also appear to be a global trend.

“About half of the major parties in established democracies now use primaries or some other representative method to give the rank-and-file more of a say in choosing their standard bearers,” wrote Moises Naim, scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in his book “The End of Power.”

Such a phenomenon is a reflection of power “decaying” and “slipping away.”

“From Chicago to Milan and New Delhi to Brasilia, the bosses of political machines will readily tell you that they have lost the ability to deliver the votes and decisions that their predecessors took for granted,” he wrote.

The Korean political parties are now weighing their options to channel reform as their main campaign platform in the lead up to the 2016 general election.

The ruling Saenuri Party leader has called for a simultaneous open primary while the main opposition New Politics Alliance for Democracy returned with a call for new proportional representative system.

Pundits said in one way or the other, the rival parties may find it difficult to keep the nomination system for the next general election as the public’s patience is thinning over worsening regional antagonism and corruption.

“If a lawmaker wins a nomination from his party and runs for a constituency that has strong and traditional support base for his party, he or she will win the election, 100 percent,” said Yoon Pyeong-joong, a political philosophy professor at Hanshin University.

“They may bow their heads in shows of respect during election campaigns, but they do not fear the people if they already have the nomination in the bag.”

By Cho Chung-un (christory@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)