Balancing globalization and reality in the lecture hall

Lectures conducted in English have become commonplace at Korean universities in the last few years. It has been reported that universities in Seoul conduct between 20 and 40 percent of their lectures in English. A desire to keep in step with globalization and bump up Korean universities’ place in world rankings have been cited as the rationale behind the push for more English lectures. But the move toward tuition through English has met with some resistance.

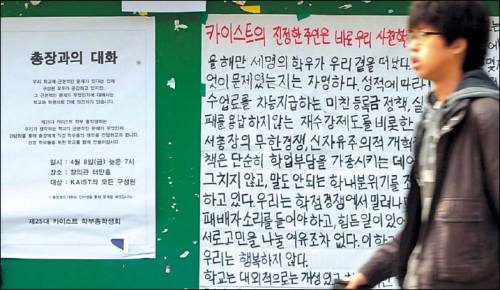

Critics say the practice puts undue pressure on students with limited English abilities and that some professors are not sufficiently competent in the language themselves. Others point to what they say is the absurdity of teaching a foreign language such as Japanese in English. Early this year, the issue was brought into sharp focus at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. A string of student suicides there was blamed on reforms introduced by its president, Suh Nam-pyo. Among the reforms was a mandate for English-only lectures. Suh later backtracked and said that alternatives to English would be provided for some subjects. For the time being, though, the move toward English lectures looks set to continue.

Yes : English is needed for future global leaders

By Daniel Suh

Before entering college, each student already has studied English for 10 years. Korea spends trillions a year on English education at private institutions, in addition to English courses at public schools.

After college, students enter the job market, where English proficiency is a major requirement particularly for Korean companies with businesses and tens of thousands of Korean employees overseas engaged in exporting, importing, and investment equivalent in size to the national GDP.

What would happen if Caltech or MIT set up a Korean branch and offered courses in English only, except for language-specific courses? I predict there would be cutthroat competition to study at the school.

No one really denies that English proficiency is crucial in the globally competitive market where English is the international language, beyond a mere foreign language.

Korean students are fairly good at listening to and reading English. Most of my POSTECH undergraduate and graduate students specifically express that they have no real difficulty in studying my economics and finance courses taught and tested entirely in English. Their outstanding test performance testifies to it.

But, Korean students’ written and spoken English is “terrible,” as my Austrian graduate student described it. A majority of my Korean students choose to write and speak Korean, while my Chinese students at POSTECH write assignments, answer exam questions, and speak excellent English.

Communication is a two-way street. You listen and read to understand the other party; you express yourself with written and spoken English. Without the latter effectively done, no communication is complete. A decade of English education in Korea still ill-equips our students for two-way communication, because students are trained primarily for college admissions with a focus on grammar and reading comprehension, but little on written and spoken English.

Now college must fill the crack and provide a bridge, moving college freshmen aspiring to become global leaders over to the globally competitive market. English lectures of college courses for aspiring students provide invaluable training, while students learn advanced academic knowledge. Such students with a decade of English study have the best education when they learn college courses in English, write English term papers and exam answers, and make English presentations. English lectures let students kill two birds with one stone.

It’s tough and painful for students and professors alike. No pain, no gain, however. It’s an intense, short-term pain at a young age, but it brings life-long gains. It also is an effective way to make up for a decade of lost opportunity of training for effective English communication and to equip our willing and capable students with an essential tool for their future global leadership and for the nation’s global competitiveness.

Why leave it to translation specialists to convert Korean documents and interpret Korean speeches? Anyone who has been seriously involved in translations and interpretations understands the tremendous value of English proficiency of the original writer or speaker for effective translation and interpretation. Any serious writer or speaker understands the inefficiency of relying on translators and interpreters often unfamiliar with terminologies and the context. The most effective English communication is made by the writer or the speaker, not translators or interpreters.

My teaching experience of economics and finance at POSTECH, has convinced me that a large number of college students are willing and capable enough to learn in English. Any college that professes to train global leaders should serve the interest of students and the nation with action, i.e., English lectures.

My answer to the debate question is a resounding affirmation for students motivated and capable enough to become future global leaders in academia, industry and government.

Daniel E. Suh is a professor of economics and finance at Pohang University of Science and Technology. ― Ed.

No : The quality of lectures is too low

By Moon Hee-jae

Korean Universities at the moment are making great efforts to have more lectures delivered in English. Some colleges are demanding “English-lecturing capability” when employing new professors. Well, let’s think about this: Is that truly good for us? Is that making the universities “globalized?” I just can’t get rid of the thought that this fashion has some problems.

First, I’m concerned about the quality of lectures in English. A plain fact is that the lecturers and the students are just not ready to have lectures in English. Yes, we learn English as the second language here, and we spend enormous time to learn it, but it doesn’t mean that Korean students are able to take lectures with that language.

Nobody can be sure about whether they can, especially when we are talking about taking major lectures. But as a college student, I can be sure about this: Even in Korean-language lectures, it is hard to understand the explanations of lecturers. What I want to say is that lectures through English would limit the information delivered and understood in the class.

The next problem is to do with the lecturers. As we know, ability to conduct research or to write an article is different from the ability to become a good teacher.

But Korean colleges don’t really care about teaching ability of professors ― this kind of ability doesn’t carry much weight in faculty evaluations, almost none. So it’s truly hard to be a good lecturer, even delivering lectures in Korean, under these circumstances.

The real problem is not here. A professor with good research ability isn’t necessarily a good teacher in their own language. In the same way, a professor with a good lecturing ability in Korean might not be a great teacher when they are lecturing in English.

So if we have English lectures without any inquiry or thought, it just makes our classes less and less efficient, reducing the lecturers’ ability to teach. I read an article saying that translating agencies are helping some professors having trouble with English lectures. Some professors needed to read from a sheet of paper!

It might not be a common thing, but still it’s unbelievable.

What I wrote were things brought up in the debate on English lectures today. But, I think we are missing the fundamental point. Before talking about the efficiency of lectures delivered in English, we must think about the necessity of English lectures. A college exists for scholarly activities, not to teach English to students!

If we need English to teach it, then we can’t help but deliver it in English, but we don’t need unnecessary work. In foreign colleges, they have English lectures in two cases: 1) if the course requires English to come across 2) If the lecturer is not able to speak the language of that country.

I don’t think the Korean universities are following these rules. And also many of these courses are not required to be in English, or at least are good when they are.

Korea’s colleges are just obsessed, obsessed about “globalization.” I can’t agree with the idea that the quantity of lectures delivered in English is an indicator of globalization. It would be if we set some standards on English lectures, thought about the fundamental necessity of that, and made college a place for scholarly activities again.

Moon Hee-jae is a senior at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies majoring in political science. ― Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)