[Visual History of Korea] 'Sehando,' painting by a literati

By Korea HeraldPublished : Sept. 17, 2022 - 16:01

Evergreen, pine and cypress trees symbolize unyielding principles and faithful devotion in Korean culture.

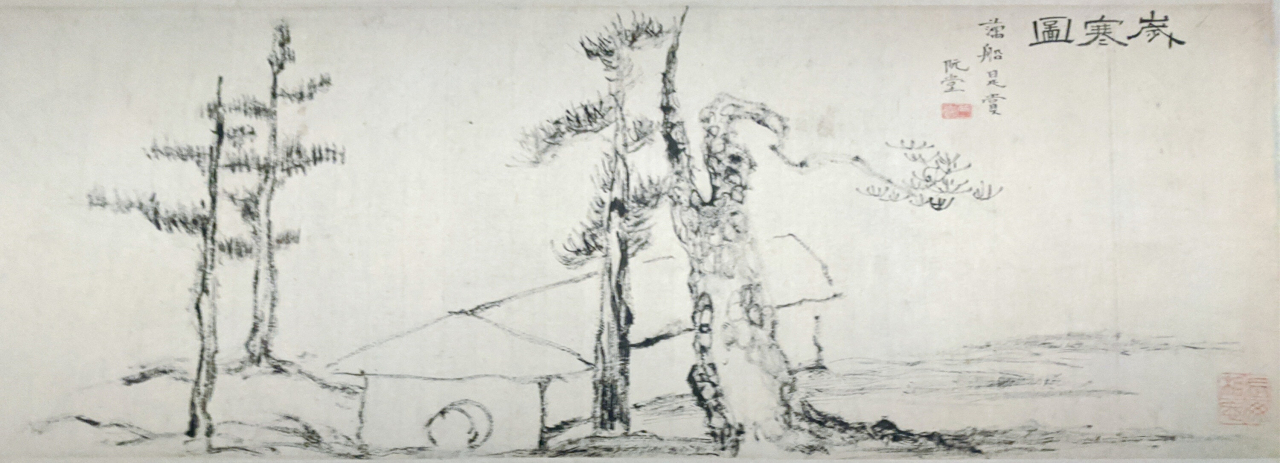

Korea's most famous painting of pine and cypress trees is named Sehando, which literally means "Age old freeze painting." It is designated as Korea's National Treasure No. 180.

Ironically Sehando was painted not by a painter but rather by a seonbi named Kim Jeonng-hui (1786 - 1856) during the Joseon Kingdom period. Seonbi were the intellectual elite of Korea.

Kim Jeonng-hui, who is better known by his pen name Chusa, was born in the shadows of Korea's royal family. Chusa's maternal grandfather was an in-law of King Yeongjo of Joseon (1694 - 1776).

Chusa was born with a silver spoon in his mouth and lived a life of luxury and wealth most of his life.

At 23, Chusa traveled to the Qing dynasty's capital city, the modern day city of Beijing, and was exposed to what was the international culture of the times.

The early 1800s was a time of great change for East Asia with western missionaries bringing new thoughts and scientific analytical approaches in academia.

Chusa espoused practical science in his twenties while mingling with elites in the Qing dynasty. His relationships with Qing elites became enduring, even when he was sent in exile behind a thorny fence in Jeju island later in his 50's.

It is said that "imitation is the greatest form of flattery."

The fundamentals of East Asian learning have always been expressed in being able to do what your teacher does.

The norm for 19th-century Korean calligraphy was not to deviate too much from predictable and precise-looking brush writings of Hanja characters.

In fact, ancient learning was mostly about memorizing the knowledge of one's teachers and learning to replicate brush strokes of your teachers.

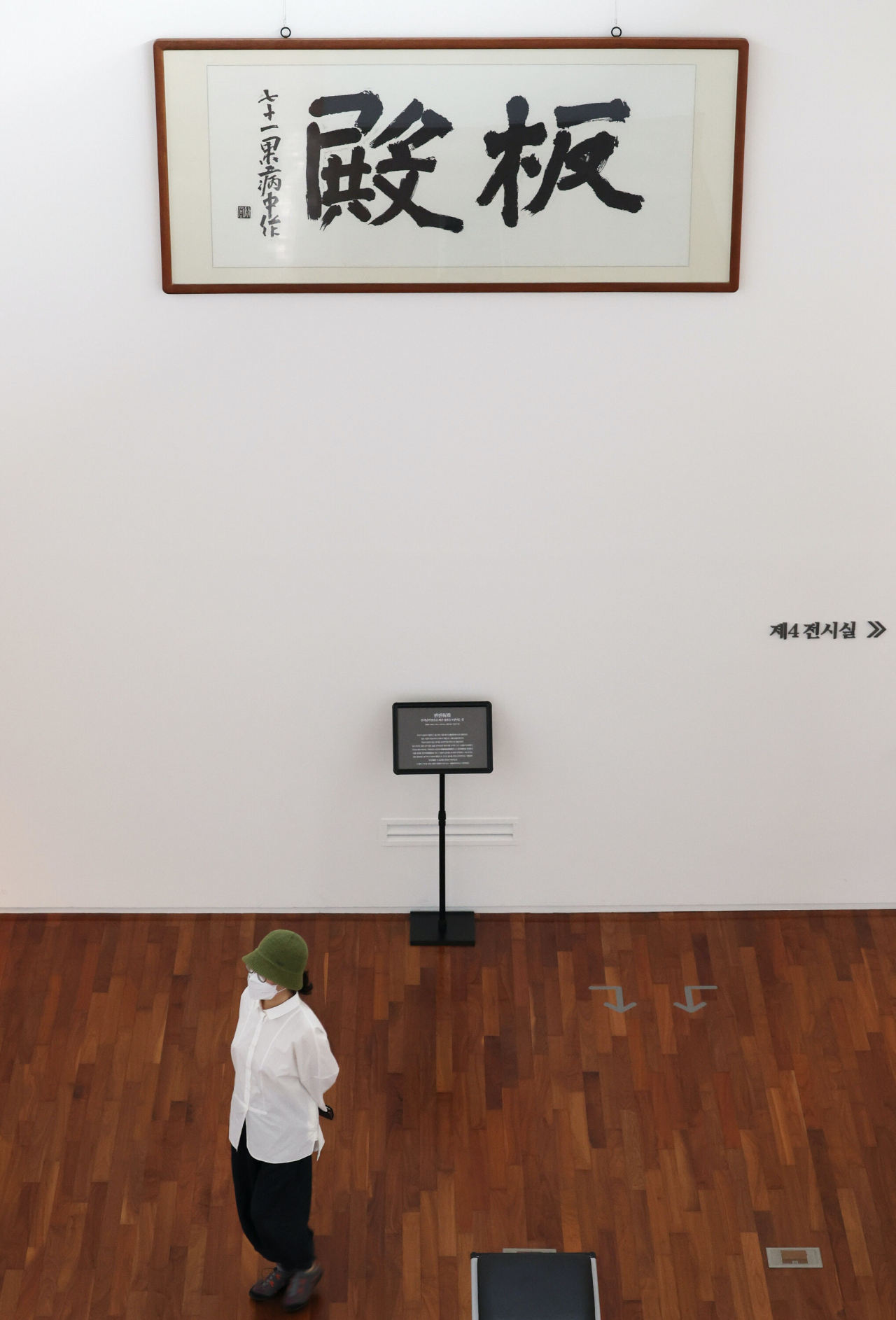

Chusa Kim Jeonng-hui created what we now call Chusa-che, the Chusa fonts.

Chusa-che boldly explores other ways to express the ideogram of the Hanja character which it symbolically represents.

For example in one of the masterpieces of Chusa's calligraphy 'Da San Cho Dang'

다산초당 (茶山艸堂) which means, 'Tea Mountain Plant House' the mountain character 'San 山' and the plant character 'Cho 艸' appear as if they are dancing. The other character 'Tea 茶' and 'Dang 堂" character look profoundly stable.

Starting at age 33, Chusa held various government posts, eventually being promoted to vice minister of the national military service. Life of a relative of the royal family meant a smooth ascent to the ruling elite class.

Political foes often accused their opponents of wrongdoings and ill intentions, as it happened often in Joseon kingdom politics.

Chusa's birth father Kim No-gyeong (1766 - 1837) was first sent in exile in 1830. He was adopted early in his life to inherit family wealth which put him on the top of the food chain in the Joseon’s upper ruling class.

In 1840 at age 55, Chusa was first severely tortured, caned and sent in exile to the island of Jeju, the most remote location from the capital city Seoul.

The journey to his exile was a long one month over treacherous mountains and crossing the waters. Chusa was placed under house arrest behind a thorny citrus fence surrounding his residence for almost 9 years.

Chusa did not stop his calligraphy and kept up with new publications in Beijing through one of his students Yi Sang-jok who brought him rare books, several carts full of books from some dozen trips to Beijing.

In appreciation for bringing him news and books, Chusa gave Yi a painting of pine and cypress trees next to a modest sizes house and named it Sehando.

"Only after it gets really cold, we can at last see that pine trees don't wither. I appreciate your steadfast friendship regardless of my house arrest." wrote Chusa on the painting.

In the 1844 Sehando painting, which measures 23cm x 69.2cm, one of the pine trees looks really old and weathered with almost no pine needles left on the tree. The tree perhaps reflects what he thought of himself in such a bleak state of life with no prospect of freedom.

The area of Jeju island where Chusa was locked up in a house arrest has some of the harshest weather on the island. This is on an island known for its absolute tough and unforgiving climate.

After being freed in 1848, Chusa was again sent in exile to Bukcheong, Hamgyeong Province, in the northern end of Korea, in 1851 and was not freed until 1853.

Chusa's obituary even appears in the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

"Chusa completed the creation of a unique Chusache font. Based on the theory of literary painting, he left many outstanding poetry and calligraphy works, and he had a high understanding of Buddhism. He spent 11 years in exile in Jeju Island and Bukcheong, Hamgyeong Province." read the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

--

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Weekender] How DDP emerged as an icon of Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050915_0.jpg&u=)

![[Music in drama] An ode to childhood trauma](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050929_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Mistakes turn into blessings in street performance, director says](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050150_0.jpg&u=20240428174656)