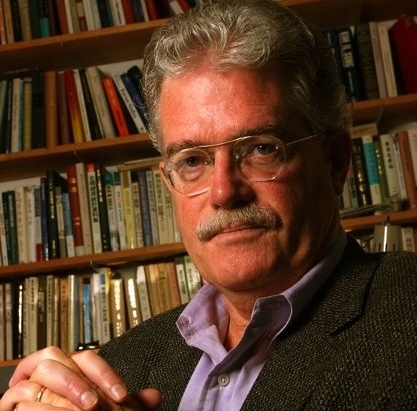

한국전쟁, 한반도 근대사의 세계적 권위자로 손꼽히는 브루스 커밍스 시카고대 역사학과 교수는 북한 핵문제를 다루는데 있어서 외교와 화해가 유일한 길이라고 주장했다. 최근 코리아헤럴드와의 단독 인터뷰에서, 그는 또한 부시 전대통령의 강경정책이 지금 북핵 위협으로 발생한 안보 딜레마의 주요원인이라고 꼬집었다.

그는 “북한은 어떤 이웃국가도 패배시킬 수 없다. 하지만 어떤 (외국) 군대도 엄청난 인명손실과 무서운 결과를 초래하지 않고 북한을 무찌르고, 정령하고, 통치하기 어려울 것이다”라고 말했다.

커밍스 교수는 이른 바 “수정주의” 역사가로 평가 받으며, 한국 보수주의자들에게 오랫동안 비난의 대상 이었다. 그는 전쟁 발발 원인을 북한의 남침 뿐만 아니라 당시 한국 내의 심화된 내전적 갈등 요소, 한국 분단에 있어서의 미국의 역할 등 기타 요인을 지적하면서 기존의 전통주의적 해석을 반박했기 때문이다.

그는 “전두환 정권의 지지자들은 내가 한국이 전쟁을 일으켰다고 주장한다고 저의 글을 폄하하고 다녔다. 이와 같은 이야기를 수없이 들었고, 일부는 사과까지 요구했다”면서 “하지 않은 말에 대해 사과하기 힘들다”라고 말했다.

다음은 커밍스 교수와의 질의응답

Q: 올해로 한국 전쟁 휴전 이후 60주년이 되었다. 휴전 협정의 의미와 특성, 역할과 과제에 대해 설명한다면?

A: 가장 특이한 정전협정이라 할 수 있다. 제1차세계대전 등과 같이 교전이 끝나고 평화회담이나 평화조약으로 이어지지 않았기 때문이다. 따라서, 이 협정은 지난 60년간 적대국 (남북한) 간의 “평화도 전쟁도 아닌” 기묘한 상태를 법적으로 보증하는 유일한 기제이었다. 또한 적대국 중 한 쪽, 즉 남한이 협정에 서명한 적이 없다는 점에서도 특이하다.

그 이외에 1954년에 제네바에서 열렸던 평화 (표면적으로는) 회담이다. 이 회의에서 공산주의 국가들과 비공산국가들이 베트남을 정치적으로 분할한 제1차 인도차이나 전쟁에 대해 유의미한 합의를 하였다. 하지만 한국관련 평화 조약에서는 결론을 내지 못했다.

나는 당시 미국이 제네바에서 아무것도 일어나지 않을 것이라고 예견했다는 사실을 미 국무부 기록을 통해 알게 되었는데, 이는 미국이 공산주의자들이 한국전에서 얻지 못한 것을 제네바 회담에서 달성하려고 시도할 것이라 예상했기 때문이기도 했다.

나는 당시 미국측 대표단의 일원이었던 U. 알렉시스 존슨에게 나는 “아무 일도 일어나지 않을 예정인 회담을 어떻게 준비하느냐”고 질문했다.

“아” 그는 일단 운을 띄운다음, “일단 연설문을 만든 다음 한국의 변 (영태) 외교부 장관이 자리를 확실히 잡고 무엇을 할지 확실히 알고 있다는 점을 확인한 다음에…이승만 대통령이 훼방(sabotage)을 놓지 않게 하는 거죠”라고 답했다.

이 때는 누구도 60년이 지난 지금까지 이 휴전 협정이 한국에서 평화를 보증하는 역할을 하리라고는 생각치 못했을 것이다. 그러나 최종적인 평화조약이나 합의 없는 이 협정의 힘은 여전히 미약하다.

리언 파네타 전 미국 국방 장관이 2012년 봄에 우리(미국)가 몇 주, 몇 달동안 북한과 전쟁으로 부터 “고작 몇 인치 정도의 거리만을 두고 있다”고 말할 수 있는데, 이는 미국이 정책상 거대한 실패를 한 것을 인정하는 것과 동시에, 휴전협정의 근본적인 약점이 있다는 것을 인정하는 것과 다름없다.

협정은 열전을 멈추었지만, 전쟁이 확실히 종결된 것은 아니다.

Q: 냉전과 관련해 한국 전쟁의 의미, 그리고 이 전쟁이 한국 사회 전반에 미친 영향에 대해 어떻게 생각하는가? 어떻게 손을 써볼 정도로 없이 심화된 이념적 대립은 한국 전쟁이 남긴 유산 중 하나로 보인다.

A: 최소한 1998년에서 2008년까지 김대중, 노무현 정부 하에서는 한국인들이 이념적 갈등을 극복하는데 상당한 성과 를 냈다고 본다. 60세 이하의 국민들은 1945년에서 1953년 사이 한국인들을 서로 갈라놓았던 끔찍한 투쟁들을 경험할 수 없었을 것이고, 이 단순한 사실이 비무장 지대(DMZ) 양쪽에 있는 강경파와 주전파들에게 있어서는 문제점으로 다가오고 있다.

젊은이들은 한국을 그동안 갈라놓았던, 사람들의 깊숙한 내면에 있는 분노와 원한들을 갖고 있지 않기 때문에 이들은 국가적인 갈등을 극복하는데 있어 가장 큰 희망인 것이다.

한국전쟁 관련 주목 받지 못한 부분은 한국전 이후 어떻게 남북한 간의 치열한 개발 경쟁이 발생했냐는 것이다. 북한은 휴전 이후 25년간 개발경쟁에서 앞서나갔으며, 그 이후로는 남한이 계속 앞서고 있다.

양측 모두 냉전 도중 초강대국의 지원을 받았으며, 남한이 받은 원조의 규모가 더 크긴 하지만 양국 모두 어마어마한 양의 해외 원조를 받았다. 또한 양국 모두 제3세계 국가 개발의 ‘분신(avatar)’이 되었는데, 북한은 60년대, 남한은 7, 80년대에 이러한 성향이 강하게 보였다.

북한경제가 현대적 토대에 걸맞도록 재건된다면, 그리고 남북한이 통일된다면, 하나의 진정한 경제강국이 탄생할 것이다.

Q: 북한은 핵실험을 세차례 강행하였고, 스스로를 핵보유국이라 주장하고 있다. 또한 북한은 미국이 ‘핵위협’을 그치지 않는다면 계속해서 실험을 지속할 것이라고 밝혔다. 북한이 핵보유에 대한 야심을 버릴 것이라고 생각하는가?

A: 북한의 핵포기는 미국이 북한을 핵무기로 위협하지 않는다는 매우 철저한 보장 하에, 그리고 북한의 핵개발 프로그램을 되돌리지 않는다는 보장 하에 가능할 것이다.

미국과 남한이 포용정책을 바꾸는 등 최근 일어난 일들을 돌이켜 보면, 북한 군핵심세력들은 핵무기를 몇 기나 보유하고 있는지, 그리고 이들을 중/장거리 미사일의 위력이 얼마나 되는지에 대해 전략적으로 모호한 태도를 유지하고 싶어할 것으로 인다.

협상을 통해 북한은 핵무기에 대해 모호성을 유지할 필요가 없는 지점에 도달 할 수 도 있을 것이다. 그것은 그들이 자신의 안보를 담보할 수 있는 핵무기를 몇 기 보유하게 될때이고 이것은 결코 외부세계가 알지 못하는 방식이 될 것이다. 그러나 이러한 핵무기는 북한이 홀로코스트를 맞을 각오를 하지 않으면 타국가를 공격하는데 실제로 사용할 수 없을 것이다. 다른 관련 국들은 북한이 추가로 플로토늄, 고농축 우라늄 그리고 장거리 미사일을 생산하지 못하도록 상한 선을 둘 수 는 있을 것이다.

2002년 이후 상황이 어떻게 변화했는지를 고려하면, 미국이 자국의 핵무기에 대해 “선(先) 사용 금지” 정책을 약속하고, 현재 보유 중인 수천개의 핵무기를 줄이려는 진지한 노력을 보이지 않는 이상 이와 같은 상황이 일어나기는 힘들어 보인다.

하지만 북한의 핵 프로그램에 상한선을 두는 것이 버락 오바마 미국 대통령의 “전략적 인내” 보다는 훨씬 나아 보인다. 실상 “전략적 안내”라는 것은 전력이 아니라 북한이 사용 가능한 핵 병기고를 만드는 걸 보고, 이에 수반되는 결과를 지켜만 볼 정도로 인내하는 것일 뿐이다.

<관련 영문 기사>

‘Diplomacy, reconciliation, only way to handle N. Korea’

By Song Sang-ho

Bruce Cumings, a leading U.S. scholar on Korea’s modern history, said diplomacy and reconciliation was the “only answer” to how to handle North Korea’s nuclear adventurism.

During an interview with The Korea Herald, the historian at the University of Chicago also criticized former President George W. Bush’s hard-line policy as the “major cause” of the current security dilemma posed by Pyongyang’s nuclear armament.

“It (the North) cannot defeat any of its near neighbors, but at the same time, it is still very hard to see how any invading army could defeat the North and occupy and govern it, without tremendous loss of life and fearsome consequences,” he said.

“So the only answer is diplomacy, reconciliation and avoiding specious and premature triumphalism.”

Labeled a “revisionist” historian, Cumings has been attacked by South Korean conservatives for challenging the traditional view of the Korean War: communists were to blame for the 1950-53 conflict.

He expressed frustration, denying that he ever said the South started the conflict.

“Supporters of the (Chun Doo-hwan) regime in and outside the government were running around trying to discredit my work by saying ‘Cumings says the South started the war!’ I don’t know how may times I heard this including demands that I apologize for saying it,” he said.

“But it is hard to apologize for something one never said.”

Following are excerpts of the interview with Cumings. The full transcript is available on the Korea Herald website.

Korea Herald: This year marks the 60th anniversary of the armistice agreement. Can you comment on the armistice agreement -- its meaning, traits, role and past, current and future challenges?

Cumings: This was a most unusual armistice agreement because unlike, say, the end of the fighting in World War I, it was not followed by a peace conference and treaty. Thus it has been the sole legal guarantor of the curious state of no war and no peace between the belligerents for the past six decades. That one of the belligerents never signed it (the Republic of Korea) also made it an unusual way to call a halt to the fighting.

Also strange was the ostensible peace conference, held in Geneva in 1954, where the communist and non-communist sides came to important agreements that ended the first Indochina war (and divided Vietnam politically), but got nowhere on a peace treaty for Korea. After learning in the State Department archives that the U.S. expected nothing to happen at Geneva (in part because the Americans thought the communists would try to get at the diplomatic table what they could not get on the battlefield), in an interview I asked U. Alexis Johnson, who was on the U.S. delegation, how one prepares for a conference where nothing is going to happen. “Oh,” he responded, “you make your speeches and you also try to make sure that Korean Foreign Minister P’yon is well established and knows what he’s supposed to do and ... you don’t let Syngman Rhee sabotage it.”

I doubt that anyone at the time thought the armistice would still be the main guarantor of peace in Korea some 60 years later, but without a final peace treaty or agreement it is still a weak reed. When former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta can say, as he did in the spring of 2012, that we have been “within an inch of war” with North Korea for weeks and months, that is both an admission of a colossal failure in American policy, and of the fundamental weakness of the armistice. It halted a hot war, but certainly did not end it.

KH: Your analysis of the cause of the Korean War has triggered much controversy. Can you again explain your understanding of the cause and characteristics of the war for our readers?

Cumings: The human problem is that people do not read deeply researched books, which mostly appeal to professional scholars, but nonetheless they like to run around acting as if they did -- and gossiping about what they think is contained in such books. I did not write about the opening of conventional war in June 1950 until 1990, when the second volume of my Origins of the Korean War appeared. Yet by the mid-1980s, after the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship had banned my first volume (which appeared in 1981), supporters of that despicable regime, in and outside the government, were running around trying to discredit my work by saying “Cumings says the South started the war!” I don’t know how many times I heard this -- including demands that I apologize for saying it.

I wrote 33 chapters on the origins of this war, and only one was titled “Who Started the Korean War?” There I presented several scenarios for how the war might have started, based on the existing documentation at the time, with the whole point of the chapter being to deconstruct the idea that the war “started” in June 1950. The theme of both my volumes was that the essential conflict began in the 1930s, between Korean forces resisting the Japanese and Korean forces serving the Japanese, between people who supported a very oppressive land system and those who did not, etc., a conflict that was vastly accelerated by events that occurred from 1945 to 1950.

By 1949, the militants who knew how to use the weapons of war were arrayed on either side of the 38th parallel, with the U.S. having put in place and supported former Japanese army officers like Kim Sok-won (who commanded the parallel during the summer and early fall of 1949), and the Russians and Chinese backing militants who had fought the Japanese going back at least to 1932. Here was a perfect recipe for civil war.

To understand June 1950 one needs to understand the border fighting along the parallel that was begun by South Korean forces in May 1949, and which continued until December 1949 -- the North Koreans initiated much fighting, of course, but according to secret reports by the U.S. commander on the scene, Gen. Roberts, the majority of the fighting was started by the southern side. A real crisis came in August 1949, when the North attacked a hilltop emplacement north of the 38th parallel that was occupied by southern troops, and quickly routed them -- to the point that the Ongjin Peninsula, south of Haeju, seemed about to fall to northern forces. Syngman Rhee wanted to counter that by attacking Cheorwon, north of the parallel. U.S. Ambassador (John J.) Muccio restrained him, worried that a war would break out; at virtually the same time, Kim Il-sung was restrained by the Soviet ambassador from widening the conflict into what the ambassador called a civil war.

KH: What do you think about the implications of the Korean War? Ideological division that seems to be insurmountable could be one example of its impact on Korean society.

Cumings: Well, in the post-Cold War era Koreans made great progress at overcoming the ideological divisions, at least from 1998 to 2008 under Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. Any person under 60 cannot have experienced the terrible struggles that divided Koreans from 1945 to 1953, and this simple human fact is a problem for all the hard-liners and warmongers on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone. Young people do not have -- and really cannot have -- the visceral hatreds and grudges that kept Korea divided for so long, and so they are the greatest hope for finally overcoming the national division.

A little-noted aspect of the Korean War is the way in which it set up a sharp competition for development between the South and the North. The North won this race for about 25 years after the armistice, and the South has won it ever since. With firm big-power backing during the Cold War, both sides were recipients of huge amounts of foreign aid (although the South got much more than the North), and both became avatars of Third World development — the North primarily in the ’60s, and the South in the ’70s and ’80s. Once the North Korean economy is rebuilt on a more contemporary basis, and if the two Koreas can ever be reunited, a real economic powerhouse will be in place.

KH: North Korea has conducted nuclear tests three times and it claims that it is already a nuclear-armed state. Do you think Pyongyang will ever renounce its nuclear ambitions?

Cumings: This renunciation would happen only under very tight guarantees that the U.S. would not threaten it with nuclear weapons, and only if others do not try to roll back the clock on the North’s nuclear programs. After what has transpired in recent years, with both the U.S. and the South dramatically reversing their stances of engagement toward the North, I think any general in Pyongyang would want to maintain ambiguity about how many nuclear weapons they might possess, and how effective their medium- and long-range missiles might be. Through negotiations the North can probably be brought to a point of “useless ambiguity,” that is, they get to keep a few nukes to make them feel secure (outsiders could never find them all anyway), but which cannot be used against others without a holocaust descending on the North; meanwhile the other diplomatic parties would achieve a cap on further production of plutonium, highly-enriched uranium, and long-range missiles.

Given how far things have come since 2002, I don’t see how this can occur without the U.S. pledging a “no-first-use” policy on its own nukes, while making much more serious attempts to reduce the thousands of nuclear weapons in its own arsenal. Unfortunately, that seems about as likely as the North giving up its nukes. But a cap on the North’s programs is much better than President Obama’s policy of “strategic patience,” which isn’t a strategy but it is very patient -- patient enough to stand by and watch the North develop a fully-usable nuclear arsenal, with attendant consequences for the Northeast Asian region.

KH: There has been much talk about the possible collapse of the reclusive regime in Pyongyang. But there has not been much talk of reunification. What do you think about the possibility of reunification and what kinds of efforts do you think should be made in preparation for it?

Cumings: I have said and written since the Berlin Wall fell that whoever anticipates or expects or seeks to impose a collapse of the North will be likely to find themselves in the second Korean War. But to the contrary, we have had almost a quarter-century of drivel on “the coming collapse of North Korea.” This even became the policy of the Clinton administration in the mid-1990s, until William Perry and others, with much help from Kim Dae-jung, came to understand that the North was not going to collapse, so it had to be dealt with “as it is, not as we would like it to be.” At the time this phrase struck me as a bolt out of the blue, a sudden glimmer of American sobriety amid a host of ignorant, failed and useless assumptions about the North going back to 1945. This was the peculiar, unexpected, enhanced clarity at the basis of the 2000 missile agreement and the engagement toward normalized relations that should have succeeded it.

The problem in understanding the North and grasping its behavior is hardly ever at the level of facts or daily events or episodes that come and go -- or about which Kim runs the country. It is at the level of scraping our own assumptions to the bone, to try and figure out a place that one may hate and revile, but that specializes in difference from beliefs that we hold dear, that will not do what we want them to do, and that persists no matter how many times we huff and we puff and try to blow their house down.

As to preparations for unification... my own view is that no unification will occur in the next few decades without prolonged efforts at engaging the northern leadership, pursuing sincere reconciliation, treating northerners fairly, and respecting their human dignity and their history.

KH: What frustrates Koreans is the stark reality that reunification is not something Koreans can realize alone given that it is an international issue. What do you think?

Cumings: At the risk of harping on the events of 2000, U.S. support for the missile deal and for President Kim’s efforts at reconciliation, the June summit, etc., was predicated on the U.S. being the guarantor and the facilitator of reconciliation and eventual reunification. Kim Jong-il agreed at the summit that American troops could remain in the South for the foreseeable future, so long as they stayed in the South. He was fearful of Korea’s geostrategic position, with China and Japan both being strong at the same time, for the first time in modern history. The U.S. would thus emerge as the closest ally of a unified Korea, able thereby to balance Japan, China and Russia while maintaining its commitments to Korea and the security architecture that it had built in the region since 1945. This was a matter of bringing the North into that system, as a neutral or innocuous party for some time to come.

This plan would not place South Korean or American troops on the Chinese border after reunification, something Beijing fears, and Korean reconciliation would not come at the expense of any of its neighbors. As a Korean strategy, this idea can be seen as early as the 1880s: to remain friendly with Korea’s neighbors, but to ally with the U.S., which has the virtue of being across the vast Pacific -- and thus less attentive.

China is much stronger in 2013 than it was in 2000, and may demand to be a central part of any Korean reunification. As for Japan, it will do what the U.S. tells it to do, as it has since 1945 (when dealing with major issues). Russia is not strong enough in the region to oppose such an outcome.

Ultimately, Korea is for the Koreans. It always has been, until the past century -- for millennia, Koreans have been the well recognized people who live on the peninsula below the Yalu and Tumen rivers. Since 1953 Koreans have imposed upon themselves (with much foreign help) a division system that, as Dr. Paik Nak-chung has shown in his work, systematically works against unification. I think the record of the past 100 years shows that if Koreans don’t care about their own interests, we can be sure no one else will. If their interest is truly unification, they can surely accomplish it with their own hands.

(sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

‘Diplomacy, reconciliation, only way to handle N. Korea’

By Song Sang-ho

Bruce Cumings, a leading U.S. scholar on Korea’s modern history, said diplomacy and reconciliation was the “only answer” to how to handle North Korea’s nuclear adventurism.

During an interview with The Korea Herald, the historian at the University of Chicago also criticized former President George W. Bush’s hard-line policy as the “major cause” of the current security dilemma posed by Pyongyang’s nuclear armament.

“It (the North) cannot defeat any of its near neighbors, but at the same time, it is still very hard to see how any invading army could defeat the North and occupy and govern it, without tremendous loss of life and fearsome consequences,” he said.

“So the only answer is diplomacy, reconciliation and avoiding specious and premature triumphalism.”

Labeled a “revisionist” historian, Cumings has been attacked by South Korean conservatives for challenging the traditional view of the Korean War: communists were to blame for the 1950-53 conflict.

He expressed frustration, denying that he ever said the South started the conflict.

“Supporters of the (Chun Doo-hwan) regime in and outside the government were running around trying to discredit my work by saying ‘Cumings says the South started the war!’ I don’t know how may times I heard this including demands that I apologize for saying it,” he said.

“But it is hard to apologize for something one never said.”

Following are excerpts of the interview with Cumings. The full transcript is available on the Korea Herald website.

Korea Herald: This year marks the 60th anniversary of the armistice agreement. Can you comment on the armistice agreement -- its meaning, traits, role and past, current and future challenges?

Cumings: This was a most unusual armistice agreement because unlike, say, the end of the fighting in World War I, it was not followed by a peace conference and treaty. Thus it has been the sole legal guarantor of the curious state of no war and no peace between the belligerents for the past six decades. That one of the belligerents never signed it (the Republic of Korea) also made it an unusual way to call a halt to the fighting.

Also strange was the ostensible peace conference, held in Geneva in 1954, where the communist and non-communist sides came to important agreements that ended the first Indochina war (and divided Vietnam politically), but got nowhere on a peace treaty for Korea. After learning in the State Department archives that the U.S. expected nothing to happen at Geneva (in part because the Americans thought the communists would try to get at the diplomatic table what they could not get on the battlefield), in an interview I asked U. Alexis Johnson, who was on the U.S. delegation, how one prepares for a conference where nothing is going to happen. “Oh,” he responded, “you make your speeches and you also try to make sure that Korean Foreign Minister P’yon is well established and knows what he’s supposed to do and ... you don’t let Syngman Rhee sabotage it.”

I doubt that anyone at the time thought the armistice would still be the main guarantor of peace in Korea some 60 years later, but without a final peace treaty or agreement it is still a weak reed. When former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta can say, as he did in the spring of 2012, that we have been “within an inch of war” with North Korea for weeks and months, that is both an admission of a colossal failure in American policy, and of the fundamental weakness of the armistice. It halted a hot war, but certainly did not end it.

KH: Your analysis of the cause of the Korean War has triggered much controversy. Can you again explain your understanding of the cause and characteristics of the war for our readers?

Cumings: The human problem is that people do not read deeply researched books, which mostly appeal to professional scholars, but nonetheless they like to run around acting as if they did -- and gossiping about what they think is contained in such books. I did not write about the opening of conventional war in June 1950 until 1990, when the second volume of my Origins of the Korean War appeared. Yet by the mid-1980s, after the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship had banned my first volume (which appeared in 1981), supporters of that despicable regime, in and outside the government, were running around trying to discredit my work by saying “Cumings says the South started the war!” I don’t know how many times I heard this -- including demands that I apologize for saying it.

I wrote 33 chapters on the origins of this war, and only one was titled “Who Started the Korean War?” There I presented several scenarios for how the war might have started, based on the existing documentation at the time, with the whole point of the chapter being to deconstruct the idea that the war “started” in June 1950. The theme of both my volumes was that the essential conflict began in the 1930s, between Korean forces resisting the Japanese and Korean forces serving the Japanese, between people who supported a very oppressive land system and those who did not, etc., a conflict that was vastly accelerated by events that occurred from 1945 to 1950.

By 1949, the militants who knew how to use the weapons of war were arrayed on either side of the 38th parallel, with the U.S. having put in place and supported former Japanese army officers like Kim Sok-won (who commanded the parallel during the summer and early fall of 1949), and the Russians and Chinese backing militants who had fought the Japanese going back at least to 1932. Here was a perfect recipe for civil war.

To understand June 1950 one needs to understand the border fighting along the parallel that was begun by South Korean forces in May 1949, and which continued until December 1949 -- the North Koreans initiated much fighting, of course, but according to secret reports by the U.S. commander on the scene, Gen. Roberts, the majority of the fighting was started by the southern side. A real crisis came in August 1949, when the North attacked a hilltop emplacement north of the 38th parallel that was occupied by southern troops, and quickly routed them -- to the point that the Ongjin Peninsula, south of Haeju, seemed about to fall to northern forces. Syngman Rhee wanted to counter that by attacking Cheorwon, north of the parallel. U.S. Ambassador (John J.) Muccio restrained him, worried that a war would break out; at virtually the same time, Kim Il-sung was restrained by the Soviet ambassador from widening the conflict into what the ambassador called a civil war.

KH: What do you think about the implications of the Korean War? Ideological division that seems to be insurmountable could be one example of its impact on Korean society.

Cumings: Well, in the post-Cold War era Koreans made great progress at overcoming the ideological divisions, at least from 1998 to 2008 under Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. Any person under 60 cannot have experienced the terrible struggles that divided Koreans from 1945 to 1953, and this simple human fact is a problem for all the hard-liners and warmongers on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone. Young people do not have -- and really cannot have -- the visceral hatreds and grudges that kept Korea divided for so long, and so they are the greatest hope for finally overcoming the national division.

A little-noted aspect of the Korean War is the way in which it set up a sharp competition for development between the South and the North. The North won this race for about 25 years after the armistice, and the South has won it ever since. With firm big-power backing during the Cold War, both sides were recipients of huge amounts of foreign aid (although the South got much more than the North), and both became avatars of Third World development — the North primarily in the ’60s, and the South in the ’70s and ’80s. Once the North Korean economy is rebuilt on a more contemporary basis, and if the two Koreas can ever be reunited, a real economic powerhouse will be in place.

KH: North Korea has conducted nuclear tests three times and it claims that it is already a nuclear-armed state. Do you think Pyongyang will ever renounce its nuclear ambitions?

Cumings: This renunciation would happen only under very tight guarantees that the U.S. would not threaten it with nuclear weapons, and only if others do not try to roll back the clock on the North’s nuclear programs. After what has transpired in recent years, with both the U.S. and the South dramatically reversing their stances of engagement toward the North, I think any general in Pyongyang would want to maintain ambiguity about how many nuclear weapons they might possess, and how effective their medium- and long-range missiles might be. Through negotiations the North can probably be brought to a point of “useless ambiguity,” that is, they get to keep a few nukes to make them feel secure (outsiders could never find them all anyway), but which cannot be used against others without a holocaust descending on the North; meanwhile the other diplomatic parties would achieve a cap on further production of plutonium, highly-enriched uranium, and long-range missiles.

Given how far things have come since 2002, I don’t see how this can occur without the U.S. pledging a “no-first-use” policy on its own nukes, while making much more serious attempts to reduce the thousands of nuclear weapons in its own arsenal. Unfortunately, that seems about as likely as the North giving up its nukes. But a cap on the North’s programs is much better than President Obama’s policy of “strategic patience,” which isn’t a strategy but it is very patient -- patient enough to stand by and watch the North develop a fully-usable nuclear arsenal, with attendant consequences for the Northeast Asian region.

KH: There has been much talk about the possible collapse of the reclusive regime in Pyongyang. But there has not been much talk of reunification. What do you think about the possibility of reunification and what kinds of efforts do you think should be made in preparation for it?

Cumings: I have said and written since the Berlin Wall fell that whoever anticipates or expects or seeks to impose a collapse of the North will be likely to find themselves in the second Korean War. But to the contrary, we have had almost a quarter-century of drivel on “the coming collapse of North Korea.” This even became the policy of the Clinton administration in the mid-1990s, until William Perry and others, with much help from Kim Dae-jung, came to understand that the North was not going to collapse, so it had to be dealt with “as it is, not as we would like it to be.” At the time this phrase struck me as a bolt out of the blue, a sudden glimmer of American sobriety amid a host of ignorant, failed and useless assumptions about the North going back to 1945. This was the peculiar, unexpected, enhanced clarity at the basis of the 2000 missile agreement and the engagement toward normalized relations that should have succeeded it.

The problem in understanding the North and grasping its behavior is hardly ever at the level of facts or daily events or episodes that come and go -- or about which Kim runs the country. It is at the level of scraping our own assumptions to the bone, to try and figure out a place that one may hate and revile, but that specializes in difference from beliefs that we hold dear, that will not do what we want them to do, and that persists no matter how many times we huff and we puff and try to blow their house down.

As to preparations for unification... my own view is that no unification will occur in the next few decades without prolonged efforts at engaging the northern leadership, pursuing sincere reconciliation, treating northerners fairly, and respecting their human dignity and their history.

KH: What frustrates Koreans is the stark reality that reunification is not something Koreans can realize alone given that it is an international issue. What do you think?

Cumings: At the risk of harping on the events of 2000, U.S. support for the missile deal and for President Kim’s efforts at reconciliation, the June summit, etc., was predicated on the U.S. being the guarantor and the facilitator of reconciliation and eventual reunification. Kim Jong-il agreed at the summit that American troops could remain in the South for the foreseeable future, so long as they stayed in the South. He was fearful of Korea’s geostrategic position, with China and Japan both being strong at the same time, for the first time in modern history. The U.S. would thus emerge as the closest ally of a unified Korea, able thereby to balance Japan, China and Russia while maintaining its commitments to Korea and the security architecture that it had built in the region since 1945. This was a matter of bringing the North into that system, as a neutral or innocuous party for some time to come.

This plan would not place South Korean or American troops on the Chinese border after reunification, something Beijing fears, and Korean reconciliation would not come at the expense of any of its neighbors. As a Korean strategy, this idea can be seen as early as the 1880s: to remain friendly with Korea’s neighbors, but to ally with the U.S., which has the virtue of being across the vast Pacific -- and thus less attentive.

China is much stronger in 2013 than it was in 2000, and may demand to be a central part of any Korean reunification. As for Japan, it will do what the U.S. tells it to do, as it has since 1945 (when dealing with major issues). Russia is not strong enough in the region to oppose such an outcome.

Ultimately, Korea is for the Koreans. It always has been, until the past century -- for millennia, Koreans have been the well recognized people who live on the peninsula below the Yalu and Tumen rivers. Since 1953 Koreans have imposed upon themselves (with much foreign help) a division system that, as Dr. Paik Nak-chung has shown in his work, systematically works against unification. I think the record of the past 100 years shows that if Koreans don’t care about their own interests, we can be sure no one else will. If their interest is truly unification, they can surely accomplish it with their own hands.

(sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[Weekender] Geeks have never been so chic in Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050845_0.jpg&u=)

![[News Focus] Mystery deepens after hundreds of cat deaths in S. Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/17/20240517050800_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Byun Yo-han's 'unlikable' character is result of calculated acting](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050855_0.jpg&u=)