Access to foreign news, entertainment seen changing people’s views, challenging regime

Before crossing North Korea’s border with China in 1999, Joseph Park could never have imagined seeing a South Korean soap opera.

When he visited the North about a decade later, he saw a booming black market in films, dramas and music produced in the democratic, affluent South.

Sophisticated but low-cost gadgets are being sneaked into border towns, where food and daily goods had been clandestinely dealt in since a devestating famine in the 1990s. Among the hottest items are USB-equipped MP4 players and even smartphones with an ultra-small media card, the 32-year-old university student told The Korea Herald.

“A two-gigabyte micro SD memory card with a reader is versatile. You can pop it into DVD or MP4 players and watch it on the go. The smaller, the better ― because you can hide it more nimbly.”

Before crossing North Korea’s border with China in 1999, Joseph Park could never have imagined seeing a South Korean soap opera.

When he visited the North about a decade later, he saw a booming black market in films, dramas and music produced in the democratic, affluent South.

Sophisticated but low-cost gadgets are being sneaked into border towns, where food and daily goods had been clandestinely dealt in since a devestating famine in the 1990s. Among the hottest items are USB-equipped MP4 players and even smartphones with an ultra-small media card, the 32-year-old university student told The Korea Herald.

“A two-gigabyte micro SD memory card with a reader is versatile. You can pop it into DVD or MP4 players and watch it on the go. The smaller, the better ― because you can hide it more nimbly.”

Information influx

The communist North is notorious for a complete lack of independent media, with all TVs preset to receive only state-run channels that trumpet its propaganda.

But recent surveys of defectors and visitors showed increasing exposure of its populace to outside news and entertainment, which experts hope could sow seeds of change in the totalitarian society in the long term.

In the latest analysis commissioned by the U.S. Department of State, many North Koreans were found to have become a regular audience of foreign radio as elites tune in to outside news and others seek music and cultural programs.

The study, titled “A Quiet Opening: North Koreans in a Changing Media Environment,” is based on research and interviews with 650 defectors, refugees and travelers from 2010-11.

Almost half of them said they had watched a foreign DVD and about a quarter had listened to foreign radio news by adjusting signals, according to the study conducted by InterMedia, a Washington-based consulting firm.

In its sample survey of 250 people, DVD viewership showed the sharpest rise ― from 20 percent in 2008 to 48 percent in 2010. Sales of DVD players are not illegal there.

More North Koreans are risking years of imprisonment, hard labor and torture to share the prohibited content, the study noted. As fewer citizens appear to be reporting on each other, penalties have also been enforced less in recent years.

“While the changes in the information environment documented in this report remain very small by international standards and there is little hope of any significant pushback against the regime from the ground up in the short term, they are illustrative of a potential long-term trajectory for change,” the study said.

A survey conducted early this month on 71 defectors by the state-run Korea Institute for Defense Analyses found that nearly 22 percent of respondents accessed overseas DVDs and CDs.

About 18 percent said they gained outside information via either TV or Chinese people, followed by radio with 15.5 percent, mobile phones with 6.3 percent and leaflets with 5.6 percent.

Twenty-two percent of the respondents picked South Korean news as their favorite content. Escape methods came next with 10 percent, music with 7 percent and information on Kim Jong-il with 6 percent.

Some ethnic Koreans in China are believed to be acting as intermediaries for North Koreans, delivering outside news and money from their relatives in the South.

Marcus Noland and Stephan Haggard, researchers with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, described a similar trend in their 2011 book, “Witness to Transformation: Refugee insights into North Korea.”

They found that the defectors with access to foreign media were increasingly sharing it with friends and family and had “somewhat more negative views” of the despotic government.

The shifting media environment is not only affecting the people but also the iron-fisted regime, according to Robert King, U.S. special envoy for North Korean human rights issues.

He pointed to Pyongyang’s unusual acknowledgment of failure of its April 13 rocket launch unlike its botched attempts in 2006 and 2009.

“The media environment in North Korea has changed and is changing, and with the availability of cellphones for internal communication, and greater availability of information internally, you can’t just say, ‘Let’s play patriotic songs’ so all can tune in,” King said last month in Washington.

Transition

New leader Kim Jong-un, who took power in December after the death of his father, Kim Jong-il, has shown no sign of easing the control on information.

During his 17-year rule, the late Kim tolerated the growth of underground markets after the rationing system crumbled in the 1990s, resulting in severe food shortages and the starvation of some 2 million North Koreans. But he reined them back in again for fear of an inflow of capitalism.

Still, the bustling markets have provided a forum for social communication and potentially political organizing, while catering to pressing material needs, said Noland, deputy director and a senior fellow at the Washington-based think tank.

“We found that the regime’s basic narrative ― that all the country’s problems are due to hostile foreign forces ― is increasingly disbelieved and that more and more people hold the regime accountable for their situation,” he told The Korea Herald via email.

For isolated North Koreans, South Korean media productions can trigger an awakening moment and stir their imagination of the outside world by highlighting a striking contrast between the two neighbors’ living standards, said Kang Chul-ho, a Christian minister who fled the country in 1992.

“It sort of plants a fantasy in their minds,” Kang said. “They get to know about South Korea while watching movies and dramas and realize how wrong the North’s policies were. Such experiences raise awareness and change their way of thinking.”

That stir, he said, could have helped increase the number of defectors in recent years.

More than 23,500 North Koreans have sought asylum in the South since the end of the 1950-53 Korean War, according to the Unification Ministry. The figure steadily rose each year from 1,383 in 2005 to 2,927 in 2009, although it slid to 2,376 in 2010 due to tighter border control.

“Obviously, greater understanding of the outside world, and of North Korea’s relative deprivation, would be expected to stimulate exit from the country,” Noland added.

“But the actual numbers of people leaving North Korea is influenced by many factors, most notably the rigor of policing on both sides of the border.”

China has been taking flak for repatriating defectors under a decades-old pact with the North, despite the torture, detention, forced labor or public executions they face back home.

Amnesty International estimated last month that about 200,000 people are held in six prison camps across the country by analyzing satellite imagery and refugee accounts.

The bulk of the detainees were incarcerated for violations like singing South Korean songs, according to South Korea’s National Human Rights Commission.

North Korea denies the existence of such gulags.

Implosion?

Abraham Kim, a North Korea expert and vice president at the Korea Economic Institute in Washington, said the people’s ever-growing information intake is eroding the pillar of the regime’s communist propaganda.

“We hear anecdotes of merchants and government and party officials being more involved in and the profiting of distributing these contrabands,” he said in an email interview.

“As a result, outside info is more available; those who are in charge of enforcing ideology are lax and uncommitted; and the regime loses increasing control of the periphery while resorting to greater draconian measures.”

The InterMedia survey found that a key consumer base in the North for South Korean media productions consists of the children of North Korea’s elite, who have the means to obtain and distribute the materials with relative impunity.

The study named elites and wealthy traders as the first groups to acquire new technology. The country’s elites in general rely on radio broadcasts for hard news and analysis and enjoy foreign entertainment such as movies and dramas, it said.

Given the potentially powerful influence of South Korean culture, observers forecast ― and perhaps hope for ― internal conflicts or an Arab Spring-style popular uprising.

Haggard, director of the Korea-Pacific Program at the University of California, San Diego, is skeptical of the possibility of any major revolt in the near future, citing the military-focused state’s use of a highly developed security apparatus and harsh punishment to “terrorize its population.”

“Authoritarian leaderships typically have privileged access to foreign goods and even culture; look at the Assad regime, and particularly Assad’s wife,” he said, referring to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad under fire for causing bloodshed amongst his people.

“Unfortunately, such regimes do not necessarily ‘soften’ simply because the leadership has access to abroad. However, there may be a long-term effect of exposure in the form of efforts to reform economic management.”

Kim Young-hui, a North Korean defector and specialist in the country’s economy at state-run Korea Finance Corp in Seoul, said that the information penetration is not fast enough to incite a sweeping transition in the reclusive society and the majority’s brainwashed, submissive mindset.

“The regime would have already collapsed if the impact were to spread quickly. It would take at least another decade or two,” she added.

The U.S. report also underlined the durability of Pyongyang’s political system and its lack of social cohesion and mobility for non-elites.

“Ultimately, greater change will require the sons and daughters of North Korea’s elites to do more than just copy South Korean dance moves or popular expressions; they will need to think like South Koreans and the rest of the world,” said Scott Snyder, a senior fellow for Korea Studies and director of the Council on Foreign Relations’ U.S.-Korea policy program.

“This is why we need to provide more opportunities for North Koreans to be educated abroad, so that they can truly absorb the information necessary to move North Korea toward reform,” he wrote on the think tank’s blog.

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] Mom’s Touch seeks to replicate success in Japan](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050568_0.jpg&u=)

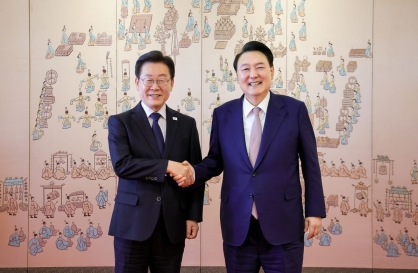

![[News Focus] Lee tells Yoon that he has governed without political dialogue](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050696_0.jpg&u=20240429210658)

![[Today’s K-pop] Seventeen sets sales record with best-of album](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/30/20240430050818_0.jpg&u=)