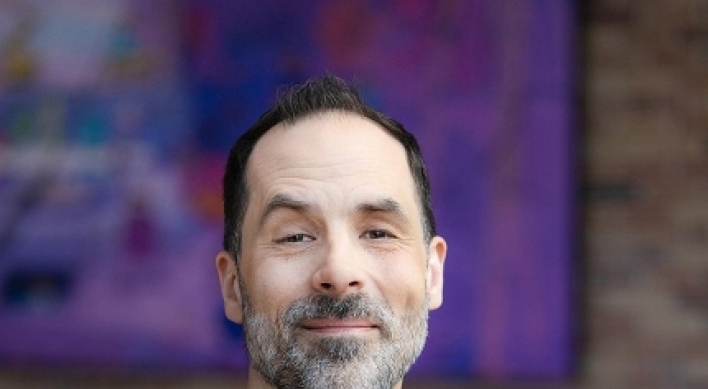

Cho Jung-goo interprets hanok in contemporary ways, while respecting tradition

The following is the final story in a series of articles on the contemporizing of Korean culture ― Ed.

The area nestled between Seoul’s Gyeongbokgung to the west and Changdeokgung to the east, known as Bukchon, is a little gem of a place where time seems to stand still.

The neighborhood where myriad alleys and “hanok,” or traditional Korean houses, have stood for nearly a century is an anomaly in a megapolis that is better known for haphazard urban redevelopment and its voracious appetite for landmark skyscrapers.

Indeed, had it not been for Seoul Metropolitan Government’s determined effort to conserve the hanok in Bukchon, this unique area may have been lost forever. The project to conserve hanok in Bukchon, which began with the designation of the area as a hanok conservation area in 1983, has, almost 30 years later, brought new life to the largely residential neighborhood: Today the area is teeming with curious tourists and casual visitors who are attracted by the unique shops, restaurants and cafes that have sprouted up in the area.

Yet there are those who question the decision to preserve hanok in Bukchon ― particularly those who favor redevelopment of the area to make way for high-rise apartment buildings ― and argue that there is little aesthetic value to the type of hanok in the area.

The hanok in Bukchon, popularly known as urban hanok, were built during the Japanese colonial era to accommodate the swelling urban population. They are houses that are more focused on function, rather than aesthetics. Here, there are no grand 99-kan hanok of the yangban ruling class. Rather, these are humble homes with two to three rooms and an enclosed madang, or courtyard.

“Architecturally, urban hanok may lack in traditional aesthetics. However, in terms of urban aesthetics, urban hanok is valuable,” says Cho Jung-goo, head of Guga Urban Architects, in defense of urban hanok.

Cho, a leading architect well-known for renovating and designing hanok in contemporized form, has been involved in updating or building more than 40 urban hanok in Bukchon.

The following is the final story in a series of articles on the contemporizing of Korean culture ― Ed.

The area nestled between Seoul’s Gyeongbokgung to the west and Changdeokgung to the east, known as Bukchon, is a little gem of a place where time seems to stand still.

The neighborhood where myriad alleys and “hanok,” or traditional Korean houses, have stood for nearly a century is an anomaly in a megapolis that is better known for haphazard urban redevelopment and its voracious appetite for landmark skyscrapers.

Indeed, had it not been for Seoul Metropolitan Government’s determined effort to conserve the hanok in Bukchon, this unique area may have been lost forever. The project to conserve hanok in Bukchon, which began with the designation of the area as a hanok conservation area in 1983, has, almost 30 years later, brought new life to the largely residential neighborhood: Today the area is teeming with curious tourists and casual visitors who are attracted by the unique shops, restaurants and cafes that have sprouted up in the area.

Yet there are those who question the decision to preserve hanok in Bukchon ― particularly those who favor redevelopment of the area to make way for high-rise apartment buildings ― and argue that there is little aesthetic value to the type of hanok in the area.

The hanok in Bukchon, popularly known as urban hanok, were built during the Japanese colonial era to accommodate the swelling urban population. They are houses that are more focused on function, rather than aesthetics. Here, there are no grand 99-kan hanok of the yangban ruling class. Rather, these are humble homes with two to three rooms and an enclosed madang, or courtyard.

“Architecturally, urban hanok may lack in traditional aesthetics. However, in terms of urban aesthetics, urban hanok is valuable,” says Cho Jung-goo, head of Guga Urban Architects, in defense of urban hanok.

Cho, a leading architect well-known for renovating and designing hanok in contemporized form, has been involved in updating or building more than 40 urban hanok in Bukchon.

“The value of urban hanok lies in the fact that it embodies the philosophy of traditional architecture while at the same time embracing the life of the people today,” Cho explains.

Cho, who has been living in an urban hanok in the Seodaemun area since 2003, knows first hand the advantages of hanok.

“It is a dwelling where you live feeling nature, the passage of time,” says Cho, explaining the significance of madang that brings nature to the very center of the house, to the center of life.

In fact, it was the need for an outdoor space after his first child was born that led him to move into hanok.

“Madang allows you to feel that you are part of nature.”

Hanok also does not force its occupants to view it in a certain way, or think of the space in a specific manner. “It is unassuming,” says Cho. In other words, it does not overwhelm the residents. “It is humane and comforting.”

The hanok dweller also knows intimately the drawbacks of traditional houses. “It is cold in winter, but this can be solved with money,” he says. Another inconvenience is the lack of storage space. “This is a problem that needs to solved,” says Cho.

Cho’s goal in designing urban hanok is to keep the mood and feel of hanok and, at the same time, allow the people living in the house to maintain their lifestyle. “Hanok is a living, expanding house,” says Cho, that can accommodate changing needs of the occupants.

Interestingly, the bulk of his clients are in their 30s and 40s, people who do not have prior experience of living in hanok. “No one has left their hanok yet,” says Cho.

Ra-gung, a hanok hotel in Gyeongju, completed in 2007, shot Cho to fame, winning him several design awards. The first-ever large-scale hanok hotel project was lauded for applying Korean tradition to a commercial space. Yet, it was several years before Cho, disappointed with the result of the developer’s hastily completed project, finally made peace with it.

“I did not like the completed work at first. The developer made changes to my design because he was in a rush. Now, my heart has softened toward it,” Cho says.

“In hindsight, it was an important project in that it showed the possibilities of hanok. It explored the possibility of combining modern function and modern language in hanok,” he says.

Ra-gung, in fact, now counts among his favorite works. Nuri, a restaurant in Insa-dong, is another favorite. “I worked freely on that project. There were no renovation codes as in Bukchon. I was able to actively interpret hanok. The project showed new possibilities,” Cho explains.

Cho is now working on large-scale hanok projects, such as a hanok village for an urban redevelopment area and hanok as commercial and public spaces. “There is a plan to build a village of hanok in Seongbuk 2-dong as part of urban renewal plan. It is at a stage now where the residents need to approve it,” he said.

“Such projects are important because getting a cluster of hanok is important. Only when there is a grouping of hanok, it becomes a stable residential area,” Cho explains.

A unique feature of hanok is the coexistence of rooms and “maru,” or an open wooden floor space, between the two main rooms of the house. Rooms are used primarily in the winter time while maru is the multipurpose space enjoyed in the summer.

Madang is distinctive in that it is not a piece of nature for viewing, but a versatile space that is actively used. “It is for everyday usage as well as for festive occasions,” Cho says.

As for the possibilities of promoting some of the unique elements of hanok, Cho points out that U.S. architect Frank Lloyd Wright, impressed with “ondol,” or floor heating system, while visiting a Japanese home whose owner had imported it from Korea., had “radiant floor heating” installed in his house. Describing it as the ideal heating system, he took out a patent on ondol and incorporated it into many of his projects. In fact, floor heating is not uncommon in the West today where it is used mainly in tiled bathrooms and kitchens.

Currently, there are about 12,000 hanok in Seoul. Cho believes it is time to explore building diverse forms of housing ― hanok, low-rise multi-unit buildings, Western-style houses ― rather than just building row after row of apartment buildings.

“Hanok is not a difficult place to live in. It is just that we have a poor understanding of our cultural assets. We also need to incorporate new ideas and technologies to hanok,” says Cho.

By Kim Hoo-ran, Culture editor (khooran@heraldcorp.com)

![[Music in drama] Rekindle a love that slipped through your fingers](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/01/20240501050484_0.jpg&u=20240501151646)

![[New faces of Assembly] Architect behind ‘audacious initiative’ believes in denuclearized North Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/01/20240501050627_0.jpg&u=20240502093000)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids go gold in US with ‘Maniac’](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/05/02/20240502050771_0.jpg&u=)