[Eye Interview] ‘Children have right to play’

Korean kids are too busy to play, while playgrounds are too safe, no fun, says playground designer Pyun

By Kim Da-solPublished : Jan. 13, 2017 - 16:37

ANDONG, North Gyeongsang Province -- Many say South Korea is a republic of convenience stores, describing the country’s some 30,000 24-hour retailers as being ubiquitous in almost every corner of Korean towns.

Yet few realize that this country of 50 million has over 60,000 playgrounds for children, twice the number of convenience stores.

Despite being in abundant supply, Korean playgrounds have major problems, according to playground designer Pyun Hae-moon. They are almost identical, risk-free to a degree that it is almost no fun and they are not as often used as they should be by their target audience -- kids.

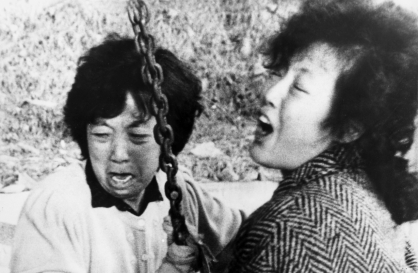

“Children not only have the right to learn. They also have right to play,” the 57-year-old play advocate stressed during an interview with The Korea Herald.

Yet few realize that this country of 50 million has over 60,000 playgrounds for children, twice the number of convenience stores.

Despite being in abundant supply, Korean playgrounds have major problems, according to playground designer Pyun Hae-moon. They are almost identical, risk-free to a degree that it is almost no fun and they are not as often used as they should be by their target audience -- kids.

“Children not only have the right to learn. They also have right to play,” the 57-year-old play advocate stressed during an interview with The Korea Herald.

Aside from the problems of playground design, Korean kids are too busy to play, spending more time being transported by yellow minibuses from one hagwon to another until their parents get home in the evening. They are also more interested in computer games and mobile phone chatting than outdoor play, Pyun lamented.

Korean kids do lead a busy life, a recent survey showed.

More than 83 percent of 5-year-olds and 36 percent of 2-year-olds in South Korea receive private education, either by going to a hagwon or home tutoring. In some cases, 5-year-olds receive up to four hours of extra classes a day after their regular kindergarten program, revealed data released earlier this week by the Korea Institute of Child Care.

A children’s book author and child education expert, Pyun has studied for the past 20 years the importance of play for children’s development and to create an ideal playground for them. To look for ideas, he traveled to many cities including Berlin, London and Tokyo.

In his opinion, a playground should be a place where children have fun, learn how to make friends and freely explore the world.

“Adults, specifically public officials, design and construct playgrounds in towns without a single chance of hearing children’s opinions. Isn’t it ironical that the main users of playgrounds are not ever heard?” Pyun asked.

He also pointed out the problem of playground standardization in Korea.

“Playgrounds should be for all children from kindergarten age to elementary school age. But as you can see, playgrounds in Korea look like they are just for kindergarten kids,” he said.

In May last year, he made the maiden step toward his long-held goal of presenting kids with an alternative playground.

His first “Miracle Playground,” in Suncheon, South Jeolla Province, bears no similarity to the ones already existing.

It has no swings, seesaws or slides. Instead of rubber turf, which has become almost a norm for Korean playgrounds, the ground is filled with sand or covered with grass. Tree trunks and stones resemble how they would look in the wild. Children can climb and jump on them, strip a bark off a tree or even just roll down a grassy hill.

Korean kids do lead a busy life, a recent survey showed.

More than 83 percent of 5-year-olds and 36 percent of 2-year-olds in South Korea receive private education, either by going to a hagwon or home tutoring. In some cases, 5-year-olds receive up to four hours of extra classes a day after their regular kindergarten program, revealed data released earlier this week by the Korea Institute of Child Care.

A children’s book author and child education expert, Pyun has studied for the past 20 years the importance of play for children’s development and to create an ideal playground for them. To look for ideas, he traveled to many cities including Berlin, London and Tokyo.

In his opinion, a playground should be a place where children have fun, learn how to make friends and freely explore the world.

“Adults, specifically public officials, design and construct playgrounds in towns without a single chance of hearing children’s opinions. Isn’t it ironical that the main users of playgrounds are not ever heard?” Pyun asked.

He also pointed out the problem of playground standardization in Korea.

“Playgrounds should be for all children from kindergarten age to elementary school age. But as you can see, playgrounds in Korea look like they are just for kindergarten kids,” he said.

In May last year, he made the maiden step toward his long-held goal of presenting kids with an alternative playground.

His first “Miracle Playground,” in Suncheon, South Jeolla Province, bears no similarity to the ones already existing.

It has no swings, seesaws or slides. Instead of rubber turf, which has become almost a norm for Korean playgrounds, the ground is filled with sand or covered with grass. Tree trunks and stones resemble how they would look in the wild. Children can climb and jump on them, strip a bark off a tree or even just roll down a grassy hill.

Since its opening, an average of 2,000 children and parents have visited the playground each week. In October, it was given an award for the country’s best public construction by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, for its creative and eco-friendly design.

“Miracle Playground serves to allow children to play creatively and nurture the spirit of adventure, unlike normal playgrounds which all look the same,” said Pyun.

He plans to build 10 more of them over the next five years.

No risk, no fun

When Pyun visited Northern European countries, he found that playgrounds there not only had varying designs and different kinds and sizes of play equipment, but they are frequented by fathers who bring their children out to play.

“These fathers are called ‘Latte Papa,’ as they bring a cup of coffee and just wait until their children are done with playing, unlike in South Korea where mothers stick to their kids to teach them how to use the slide and where to step on the climbing wall,” he said.

Pyun criticized many Korean parents as overly protective. Without realizing it, they often block their kids from any chance of exploring their world freely and nurturing an adventurous spirit.

“Korean parents are typically very worried about all sorts of potential risks outside. But public playgrounds are the best place for children to learn about risks, like how to detect and overcome risks,” he said, stressing that children grow by experiencing healthy risks.

Risks are different from hazards, he went on.

“Risks are like passing through a shaking bridge and hazards are broken glass pieces on the ground. But parents sometimes mistake the two.”

By crossing shaky bridges at playgrounds, children can learn to ask themselves, “Will it be safe to cross this bridge?” and learn to hold onto something that is stable.

In European countries, such as the UK, playgrounds are required to include pre-designed “risk items,” Pyun said.

The boom in such playgrounds started in the mid-1940s in Europe and 1970s in Japan, while the number of adventurous playgrounds around the globe has surged to over 1,300, mostly in Europe.

Following the trend growing outside Korea, the Seoul Metropolitan Government for the first time in Seoul began test operating a new type of public playground called Adventure Park -- filled with wooden poles and hills -- in a Northeastern town in Dobong-gu last week.

Just let them play freely

Korean parents also need to redefine children’s play, said Pyun who has authored books on the topic including “Play is Food for Children.”

Quoting Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, he said that parents should not approach children’s play with a certain purpose. Letting children play is not about helping them release mental stress or becoming smarter, more creative or any certain type of person.

“It is rather a concept of freedom for children,” said Pyun, who is himself a father of two children.

Many young parents trying to be “good parents” feel obliged to take their kids out to fun places and allow them to have educational experiences, such as amusement parks, exhibition halls and aquariums.

“Remember that children do not find it fun only when they visit amusement parks or theme parks. Parents do not need to visit or create special spaces for playing, as children simply mimicking their mother’s cooking in the kitchen could become a good play activity for them.”

The No. 1 virtue for parents in Korea is a sense of balance, not to be easily tempted to buy expensive new toys for their kids or send them to hagwon, simply because many others parents do.

“Children learn at each and every stage of life what joy is and what fun is. It is important for parents to let them fully experience all these stages through unstructured play, especially when they are young.”

Pyun’s wife Park Bo-young, who was also present at the interview, added, “As a mother, I also find myself controlling my children from A to Z. I think it is partly because I never got to know the freedom of play when I was a child.”

“Now I am a parent, but I am still learning how to communicate with children, nurture inner balance in them and help them experience freedom through play,” the cartoonist added.

By Kim Da-sol (ddd@heraldcorp.com)

“Miracle Playground serves to allow children to play creatively and nurture the spirit of adventure, unlike normal playgrounds which all look the same,” said Pyun.

He plans to build 10 more of them over the next five years.

No risk, no fun

When Pyun visited Northern European countries, he found that playgrounds there not only had varying designs and different kinds and sizes of play equipment, but they are frequented by fathers who bring their children out to play.

“These fathers are called ‘Latte Papa,’ as they bring a cup of coffee and just wait until their children are done with playing, unlike in South Korea where mothers stick to their kids to teach them how to use the slide and where to step on the climbing wall,” he said.

Pyun criticized many Korean parents as overly protective. Without realizing it, they often block their kids from any chance of exploring their world freely and nurturing an adventurous spirit.

“Korean parents are typically very worried about all sorts of potential risks outside. But public playgrounds are the best place for children to learn about risks, like how to detect and overcome risks,” he said, stressing that children grow by experiencing healthy risks.

Risks are different from hazards, he went on.

“Risks are like passing through a shaking bridge and hazards are broken glass pieces on the ground. But parents sometimes mistake the two.”

By crossing shaky bridges at playgrounds, children can learn to ask themselves, “Will it be safe to cross this bridge?” and learn to hold onto something that is stable.

In European countries, such as the UK, playgrounds are required to include pre-designed “risk items,” Pyun said.

The boom in such playgrounds started in the mid-1940s in Europe and 1970s in Japan, while the number of adventurous playgrounds around the globe has surged to over 1,300, mostly in Europe.

Following the trend growing outside Korea, the Seoul Metropolitan Government for the first time in Seoul began test operating a new type of public playground called Adventure Park -- filled with wooden poles and hills -- in a Northeastern town in Dobong-gu last week.

Just let them play freely

Korean parents also need to redefine children’s play, said Pyun who has authored books on the topic including “Play is Food for Children.”

Quoting Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, he said that parents should not approach children’s play with a certain purpose. Letting children play is not about helping them release mental stress or becoming smarter, more creative or any certain type of person.

“It is rather a concept of freedom for children,” said Pyun, who is himself a father of two children.

Many young parents trying to be “good parents” feel obliged to take their kids out to fun places and allow them to have educational experiences, such as amusement parks, exhibition halls and aquariums.

“Remember that children do not find it fun only when they visit amusement parks or theme parks. Parents do not need to visit or create special spaces for playing, as children simply mimicking their mother’s cooking in the kitchen could become a good play activity for them.”

The No. 1 virtue for parents in Korea is a sense of balance, not to be easily tempted to buy expensive new toys for their kids or send them to hagwon, simply because many others parents do.

“Children learn at each and every stage of life what joy is and what fun is. It is important for parents to let them fully experience all these stages through unstructured play, especially when they are young.”

Pyun’s wife Park Bo-young, who was also present at the interview, added, “As a mother, I also find myself controlling my children from A to Z. I think it is partly because I never got to know the freedom of play when I was a child.”

“Now I am a parent, but I am still learning how to communicate with children, nurture inner balance in them and help them experience freedom through play,” the cartoonist added.

By Kim Da-sol (ddd@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)