[Eye Interview] A bank for modern-day Jean Valjeans

Microcredit group helps petty offenders who go to jail because they couldn’t afford to pay penalty

By Kim Da-solPublished : May 12, 2017 - 18:11

In “Les Miserables,” Victor Hugo’s 1862 classic set in the French Revolution, the main protagonist Jean Valjean ends up spending 19 years in prison for stealing a loaf of bread to feed his sister’s starving children.

In South Korea in 2015, a bank opened to help modern-day Jean Valjeans, poor petty offenders who go to jail because they can’t afford to pay a few million won in fines and penalties.

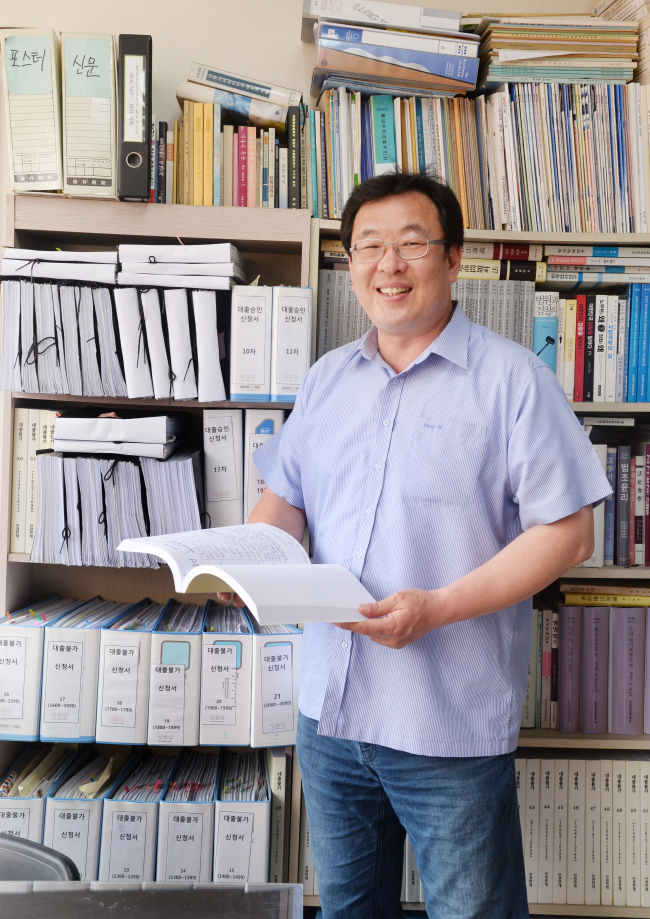

“As long as their offenses are not grave, we consider lending,” Oh Chang-ik, head of the Jean Valjean Bank said during an interview with The Korea Herald.

Every year, approximately 40,000 small-time offenders go to jail and endure prison labor because of their failure to pay penalties, he explained.

Since its inception two years ago, the microcredit scheme has offered some 460 minor criminals loans totaling 8 billion won ($7 million).

Of them, 66 debtors have fully paid off their loans, while 241 others are in the process of doing so, as of this week, according to Oh.

The bank provides up to 3 million won per person, with no interest and no collateral. Debtors are asked to repay six months to a year later.

All it asks for is a written statement of why they need the money and a copy of the applicant’s family registration document via email or mail.

Of course, it has its own screening standards.

“We look at how much they need the money and their family situation, for example whether the applicant is a single mother with young children,” said Oh who doubles as the secretary-general of Citizens’ Solidarity for Human Rights, which initiated this project in February 2015.

“We do not give out loans to offenders of sexual crimes or those caught for drunk driving. The money is for offenders of a crime that did little social harm,” he said.

Those who committed heinous crimes such as murder and robbery, economic crimes like bribery and embezzlement and habitual offenders are also ruled out.

Oh said the bank receives approximately 180 applications monthly.

Priority is given to teenagers living by themselves, young heads of the family, recipients of the basic livelihood security benefits and people living just above the poverty line.

“Personally, I want to help young offenders in poverty so that they don’t have to spend time behind bars,” he said.

The microcredit bank started with just 10 million won from Citizens’ Solidarity for Human Rights.

Relying entirely on donations, Oh had some concerns in the beginning that the bank may run out of funds, if donations fall short or loan defaults rise.

“But thankfully, that has not happened,” Oh said.

Quite to the opposite, its loan pot has grown to 800 million won at this moment, as donations grew and many debtors paid off in full.

Nearly 4,300 individuals and groups have made contributions. Among them are some former debtors.

“Interestingly and gratefully, some people, a few years after they received our loans, sent us their donations from 10,000-20,000 won,” Oh said.

Oh’s ultimate dream is that one day Jean Valjean Bank is not needed anymore.

“If no one goes to prison because of poverty, our bank will have no work to do. I hope that day will come,” he said.

The activist also said that the government has a key role to play.

Under the current law, one who is sentenced to a financial penalty must make the full payment in 30 days.

“I believe the current disciplinary provision has a lot to improve. Making criminals do labor in prison just because they cannot afford to pay fines is meaningless and gives them unnecessary pain.”

Quoting Article 11 of the Constitution that all citizens are equal before the law, Oh stressed that the system is unfair for poor offenders.

Rich offenders walk free, while poor ones go to jail to make up for the financial penalty which is set regardless of one‘s income level.

“In our society, income inequality is leading to unequal punishment.”

By Kim Da-sol (ddd@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)