COMMES, France (AP) ― Weather conditions over Normandy had been iffy for days. Showers and wind in the morning gave way to glorious spring sunshine in the afternoon, then electric green lightning storms over the sea at night.

We watched the sky and waited for the go sign ― the signal that meant it was time to jump. With a brief window of only a few hours in which it would be possible, I began to doubt our chances.

Finally the message my companions and I had been waiting for arrived: The jump was on.

Unlike the paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions who jumped into Normandy at the start of D-Day 70 years ago, our orders came not from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, but via text message from our paragliding instructor.

My wife and I had come to Normandy ahead of the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings to explore the region’s rich history, cuisine and culture.

I’d been to the U.S. military cemetery at Omaha Beach years before, a trip that’s still a must for many Americans visiting France.

But this time we wanted to explore farther afield. We’d crisscross the picturesque rural region from the famous cheese-making town of Pont l’Eveque in the east to the isolated Gatteville Lighthouse near the rugged granite-hewn village of Barfleur in the west.

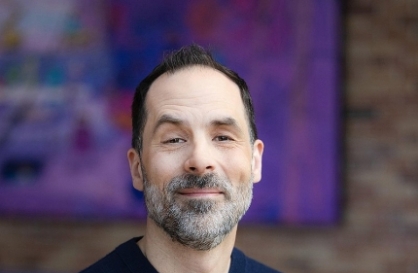

Just a few miles from Omaha Beach, Claude Bellessort runs Elementair, a paragliding school in Port-en-Bessin. An expert pilot with years of experience leading paragliding excursions to places as far afield as Nepal and Morocco, Bellessort has offered tandem paragliding flights here since 2002.

We watched the sky and waited for the go sign ― the signal that meant it was time to jump. With a brief window of only a few hours in which it would be possible, I began to doubt our chances.

Finally the message my companions and I had been waiting for arrived: The jump was on.

Unlike the paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions who jumped into Normandy at the start of D-Day 70 years ago, our orders came not from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, but via text message from our paragliding instructor.

My wife and I had come to Normandy ahead of the 70th anniversary of the D-Day landings to explore the region’s rich history, cuisine and culture.

I’d been to the U.S. military cemetery at Omaha Beach years before, a trip that’s still a must for many Americans visiting France.

But this time we wanted to explore farther afield. We’d crisscross the picturesque rural region from the famous cheese-making town of Pont l’Eveque in the east to the isolated Gatteville Lighthouse near the rugged granite-hewn village of Barfleur in the west.

Just a few miles from Omaha Beach, Claude Bellessort runs Elementair, a paragliding school in Port-en-Bessin. An expert pilot with years of experience leading paragliding excursions to places as far afield as Nepal and Morocco, Bellessort has offered tandem paragliding flights here since 2002.

The thrill of taking off from the cliff top and swooping over the beaches, imagining how it appeared on D-Day, made the 10-minute flight an unforgettable highlight of three days in Normandy.

Local officials estimate that the invasion anniversary will attract several hundred thousand tourists to Normandy this summer. The commemorations culminate June 6 in Ouistreham, where U.S. President Barack Obama, French president Francois Hollande and Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II will gather to remember the more than 9,000 Allied soldiers killed or wounded that day.

We spent the night after our jump in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, a tiny village in Omaha Beach. This was one of the invasion’s five famous landing areas spread over 80 kilometers of coast where 160,000 U.S., British and Canadian troops came ashore on D-Day. Omaha, where the U.S. 1st and 29th divisions landed, saw some of the day’s bloodiest fighting and worst casualties.

To look out to sea here or at the nearby Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, and picture the scene at dawn on June 6, 1944 is breathtaking: 5,000 landing ships and assault craft assembled in the largest armada in history lined up across the horizon.

Turning to face the beach, it was impossible not to imagine the waves of infantry, “tumbling just like corn cobs off of a conveyor belt” under German machine gun fire as the first troops landed, in the words of a sergeant quoted in Antony Beevor’s authoritative history of the battle, “D-Day, The Battle for Normandy.”

Our host for the night was Sebastien Olard, 46, a bakery supply salesman and passionate amateur D-Day historian. Olard grew up in the village of 200 inhabitants, on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Fifteen years ago he bought a stone house surrounded by a sheep pasture that village elders say was the first home liberated by American troops on D-Day. He’s turned the home into a museum-cum-vacation rental called “La Maison de la Liberation” (House of the Liberation).

For 80 euros, guests can overnight in the 200-year-old house and enjoy a history lesson from the irrepressible Olard, who can talk for hours about the home’s place in D-Day history.

Olard’s grandfather, who lived in the neighboring village of Vierville-sur-Mer, feared a German counterattack after the invasion, and walked with his wife and children several kilometers down the beach to Saint-Laurent to seek evacuation to Britain. “They saw things that even today it’s hard to talk about,” Olard said. “They had to step over bodies. My grandfather told his children, ‘Don’t worry, just walk. They’re sleeping. Go!’”

There are so many D-Day museums in Normandy that it’s hard to decide which to visit on a short trip. Using a $5 smartphone app “Normandy D-Day 1944,” I narrowed our selection to two: the Battle of Normandy Memorial Museum in Bayeux and the Airborne Museum in Sainte-Mere-Eglise.

Bayeux is one of the rare cities in Normandy to escape the Allied bombardment that killed tens of thousands of civilians and destroyed centuries-old architectural monuments. The museum uses film, photographs and other artifacts to provide a detailed yet easy-to-follow overview of the battle.

The Airborne Museum narrows the focus to the story of the paratroopers who dropped behind enemy lines the night before the invasion, with a C-47 “Skytrain” aircraft that flew them from England on display.

A few miles south near Carentan, we met Franck Feuardent, the owner of the Manoir de Donville. This 18th century manor house was the site of the Battle of Bloody Gulch, made famous in an episode of the television series “Band of Brothers.” American paratroopers were nearly routed by an SS tank division until saved by the arrival of the U.S. 2nd Armored Division, aka “Hell on Wheels.”

On a tour of the manor grounds, Feuardent pointed out foxholes and let us handle examples of the 12 tons of weapons, helmets, grenades and other artifacts he’s dug up. “Two days ago I was searching the other side of this hedge, and the metal detector just started going ‘Ding! Ding! Ding!’” Feuardent said.

In his 200-year-old home, Feuardent points out traces of blood stains on the wooden floor of his sons’ bedroom, where two soldiers’ bodies, one German, one American, were discovered after the battle. “They fought hand-to-hand in my home!” Feuardent says with awe.

“We try to keep the spirit of the Americans who died here alive,” Feuardent says. “We never forget. This isn’t a museum for me, it’s my home.”

There’s much more to do in Normandy than visit war memorials. The Pays d’Auge around the small town of Cambremer is the heart of Normandy’s traditional apple cider and apple brandy-making region.

We stopped at Stephane and Lucile Grandval’s distillery, Manoir du Grandouet. The family has made cider here for three generations; one of the giant oak barrels where the heady, intoxicating apple brandy known as calvados is aged dates from 1792.

After a film and short visit at the centuries-old half-timbered farm building, Stephane heads to the attic, where apples were once stored above a 16th-century press that crushed the fruit. “When I was a boy I’d kick the apples through a hole here” down into a granite horse-powered press, he says.

His wife Lucile pours tastes of ciders and brandies, including one, the Cuvee Reserve Cidre AOC Pays d’Auge Cru de Cambremer, which won a gold medal at this year’s Paris International Agricultural Show. Lush, almost creamy, it reminds me of a sweet champagne. We buy a few bottles, and Lucile sneaks in an extra bottle as a gift. The friendly gesture reminded me of a line in the classic D-Day war film “The Longest Day,” when Gen. James “Jumpin’ Jim” Gavin of the 82nd Airborne tells his troops, “When you get to Normandy, you’ll only have one friend ― God ... and this,” lifting a rifle. For visitors today, 70 years after the invasion that helped liberate Europe from Adolf Hitler, that’s happily no longer true.

-

Articles by Korea Herald