Institute builds on global knowledge network in security, Asia, public policy

When it started out in the spring of 2002, the East Asia Institute looked no different from many independent academic projects ― pure, proud but doomed to obscurity.

Its organization was untenably tiny with only two staffers. It declared financial independence from government and businesses. Its motto ― “Ideas can change the world” ― sounded fairly idealist

A decade later, the experiment has transformed into one of the world’s most prestigious think tanks in security, international relations and public policy, churning out top-notch studies brimming with practical policy recommendations.

None of its founding principles were adulterated. It still remains free from political, corporate, and ideological interests, minuscule in manpower, and fiercely committed to the power of ideas. Behind the growth is its extensive network of knowledge and its generators, said its president Lee Sook-jong.

“We are still an experimental organization with 13 full-time staff,” Lee, a leading Japan expert and a public administration professor at Sungkyunkwan University, told The Korea Herald in an interview.

“We are aspiring to carry out independent, future-oriented and innovative research. To that aim, networking with other think tanks and intellectuals in the western world and Asia is very important.”

The think tank started first with its founder Kim Byung-kook and merely one full-time researcher. Over time, it courted several more specialists in international relations, North Korea, defense and opinion polling. Then it engaged prominent scholars from universities and research institutes at home and abroad in a swathe of joint research projects, which have grown into its “knowledge network” with a global and trans-disciplinary reach.

The Seoul-based institute shot to fame in 2009 when it was picked as one of three core institutions in the Asia Security Initiative by the MacArthur Foundation, one of the world’s largest private foundations.

Under the theme of “Northeast Asian Security Challenge,” it studies the impact of three megatrends ― globalization, democratization and information technology ― in security relations in the region with an annual funding of $600,000 from the Chicago-headquartered charity.

In January, the EAI was ranked 24th in University of Pennsylvania’s list of the world’s top 50 security and international affairs think tanks and 26th in outstanding policy-oriented public policy research programs.

The sole other domestic player that made the list was the state-run Korea Development Institute, one of the country’s largest think tanks with a brain force of more than 200.

Korea now has more than 100 public and private research organizations. But few have stood out on the international stage, casting doubt on their efficiency, the quality of work and aptitude for policy assessment and suggestions.

One reason may be that most institutes are connected to a government body, a company, a political party, an interest group or a non-governmental organization. That ownership structure concentrates them on catering to their respective clients’ needs and interests rather than acting to their own ends and agenda, Lee said.

When it started out in the spring of 2002, the East Asia Institute looked no different from many independent academic projects ― pure, proud but doomed to obscurity.

Its organization was untenably tiny with only two staffers. It declared financial independence from government and businesses. Its motto ― “Ideas can change the world” ― sounded fairly idealist

A decade later, the experiment has transformed into one of the world’s most prestigious think tanks in security, international relations and public policy, churning out top-notch studies brimming with practical policy recommendations.

None of its founding principles were adulterated. It still remains free from political, corporate, and ideological interests, minuscule in manpower, and fiercely committed to the power of ideas. Behind the growth is its extensive network of knowledge and its generators, said its president Lee Sook-jong.

“We are still an experimental organization with 13 full-time staff,” Lee, a leading Japan expert and a public administration professor at Sungkyunkwan University, told The Korea Herald in an interview.

“We are aspiring to carry out independent, future-oriented and innovative research. To that aim, networking with other think tanks and intellectuals in the western world and Asia is very important.”

The think tank started first with its founder Kim Byung-kook and merely one full-time researcher. Over time, it courted several more specialists in international relations, North Korea, defense and opinion polling. Then it engaged prominent scholars from universities and research institutes at home and abroad in a swathe of joint research projects, which have grown into its “knowledge network” with a global and trans-disciplinary reach.

The Seoul-based institute shot to fame in 2009 when it was picked as one of three core institutions in the Asia Security Initiative by the MacArthur Foundation, one of the world’s largest private foundations.

Under the theme of “Northeast Asian Security Challenge,” it studies the impact of three megatrends ― globalization, democratization and information technology ― in security relations in the region with an annual funding of $600,000 from the Chicago-headquartered charity.

In January, the EAI was ranked 24th in University of Pennsylvania’s list of the world’s top 50 security and international affairs think tanks and 26th in outstanding policy-oriented public policy research programs.

The sole other domestic player that made the list was the state-run Korea Development Institute, one of the country’s largest think tanks with a brain force of more than 200.

Korea now has more than 100 public and private research organizations. But few have stood out on the international stage, casting doubt on their efficiency, the quality of work and aptitude for policy assessment and suggestions.

One reason may be that most institutes are connected to a government body, a company, a political party, an interest group or a non-governmental organization. That ownership structure concentrates them on catering to their respective clients’ needs and interests rather than acting to their own ends and agenda, Lee said.

“What matters is the subjects they delve into and how they are operated. In that sense, we can provide an environment in which researchers initiate a project that’s free, politically neutral and devoted to its pure purpose,” she said.

“For Korean research institutes to take off, they have to transcend parochial perspectives on every area, which decreases their abilities to see the subject objectively and comprehensively. They should debate universal issues.”

Lee, 54, educated at Harvard University, took the helm at the EAI in 2008, succeeding founder Kim, a former political science professor at Korea University, former presidential security aide and now chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy.

A pool of some 100 outside experts prop up its two main pillars of research. One is peace and security in East Asia and the other is democracy and governance that also involves polls and analyses of public opinion on elections and other political, economic and social issues.

“The network was hard to create but is even harder to maintain and requires your devotion,” Lee said.

“The academics come to us not for money but for their passion and a synergy with their own work and from the horizontal collaboration, given the latitude promised to them that’s probably wider than anywhere else.”

As part of its network, the EAI forged a partnership with BBC World Service in 2005 and works with local media outlets to take public surveys here. It is a founding member of the Council of Councils, a club of 21 leading public policy research institutes launched by the Council on Foreign Relations last year.

Together with the Japan Foundation and Taiwan’s Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation, it also invites about five Western scholars in East Asia studies every year for seminars and joint research.

The scheme helps the institution surmount barriers stemming from limited resources, Lee said. On top of external grants, donations from individuals and public and private corporations are key sources of finance.

“Globalization has taken on great significance in the world knowledge network,” she said.

“The days have gone when military and economic powers demand their ideas be accepted. Now, a country small but full of ideas can offer a lot. What’s important is how to come up with innovative ideas.”

With that in view, Korea can play a “middle power” as a peace broker in a global power struggle between the U.S. and China, and add a catalyst to trilateral cooperation between Seoul, Beijing and Tokyo, she said.

“Korea is now in a position that used to be unthinkable,” Lee said, citing the country’s meteoric economic ascent and growing role in regional and world affairs.

“Despite some cynicism about the notion, I believe there are some aspects where Korea can contribute dramatically as an intermediary and dialogue channel between the U.S. and China given its good relationships with both countries and Japan’s relative decline.

“It would also be able to wisely steer three-way collaboration with China and Japan, engaging them in regional issues and neutralizing any history-driven misconceptions or miscalculations between them.”

Over the last four years, Lee appears to have become more ambitious and tempted by further experiments.

To facilitate knowledge sharing with the world, Lee plans to generate more output in English and other languages such as Chinese and Japanese. She has increasingly been interested in conceptual projects on globally hot topics such as the environment and development, while mulling ways to double the size of her lab despite financial pressure.

With her public opinion team, she aims to build a database for studies on the presidential, general and local elections. The EAI currently donates its datasets to the Korea Sociological Association.

“Korea doesn’t have an archive for public opinion-related data that can contribute to scientific research. Panel surveys involve large expenses but provide evidence for a trend in elections,” Lee said.

“These days, the interest from civil society is a must to strengthen the linkage between domestic policies and diplomacy.”

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

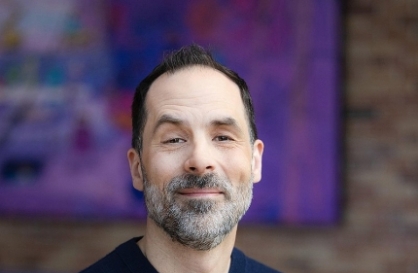

Lee Sook-jong, public policy expert

Lee Sook-jong is president of the East Asia Institute and a professor of public administration at Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul.

She took office at the independent, non-profit think tank in 2008, succeeding Kim Byung-kook, its founder and chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy.

A leading Japan specialist, she puts research priority on the civil society and democracy of Korea and Japan and the two countries’ politics and economy, as well as policy opinions.

Her recent publications include “The Demise of Korea Inc.: Paradigm Shift in Korea’s Developmental State,” “The Assertive Nationalism of South Korean Youth: Cultural Dynamism and Political Activism” and “Japan’s Changing Security Norms and Perceptions since the 1990s.”

Prior to the EAI, Lee spent 11 years as a researcher with the Sejong Institute until 2005 and was a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institute and lectured at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies in the U.S. in 2004.

Born in 1957, she earned her bachelor’s degree in sociology from Yonsei University in Seoul and master’s and Ph.D. degrees from Harvard University.