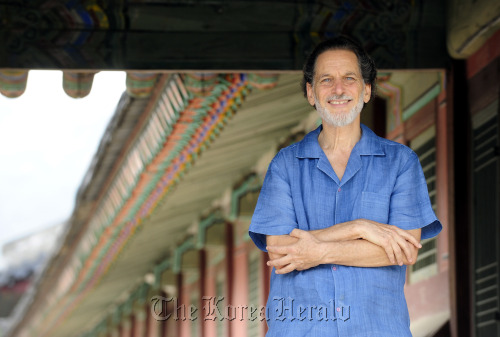

American professor documents Korean dreams over decades, builds ‘peace train’

For 20 years, one Hankuk University of Foreign Studies English professor collected the dreams of thousands of his students, their parents and their grandparents.

Soon, Fred Jeremy Seligson hopes to collate them in the first ever “Great Korean Dream Book.”

The Washington, D.C. native, once a lawyer in Ethiopia for the Peace Corps, is fascinated by the significance Koreans traditionally attach to their dreams and is the only foreign voice on the topic.

Although subject matter has included marriage, education and well-being over the years, Seligson is most known for his two books on birth ― “Oriental Birth Dreams,” and “Queen Jin’s Handbook of Pregnancy.”

Seeing the future

“Koreans have a great capacity for prophetic dreams,” said Seligson, referring to the ancient belief that if a person was clear and honest they would receive information about their future when they slept.

This was especially the case with mothers, who believed in “womb education” from China, the belief that their state of mind during pregnancy was fundamental to their child’s outcome. So what was dreamt was of great importance and could, if lucky, predict a scholar as it had for Queen Jin in China. She was the mother of sage-king Wen, author of one of the oldest Chinese texts, the “I-Ching,” or “The Book of Changes.”

In Korea, belief in the receptive and active life of the unborn child in the womb explains why babies are already one year old at birth.

“In ancient days I think this part of the brain was developed that almost everything, their news, they got through their dreams. And they would talk about their dreams when they woke up, at the well.

“I think in part it was (because it was) an isolated country and in the many little villages isolated around the country there was no TV so it was hard to get information,” he explained.

For 20 years, one Hankuk University of Foreign Studies English professor collected the dreams of thousands of his students, their parents and their grandparents.

Soon, Fred Jeremy Seligson hopes to collate them in the first ever “Great Korean Dream Book.”

The Washington, D.C. native, once a lawyer in Ethiopia for the Peace Corps, is fascinated by the significance Koreans traditionally attach to their dreams and is the only foreign voice on the topic.

Although subject matter has included marriage, education and well-being over the years, Seligson is most known for his two books on birth ― “Oriental Birth Dreams,” and “Queen Jin’s Handbook of Pregnancy.”

Seeing the future

“Koreans have a great capacity for prophetic dreams,” said Seligson, referring to the ancient belief that if a person was clear and honest they would receive information about their future when they slept.

This was especially the case with mothers, who believed in “womb education” from China, the belief that their state of mind during pregnancy was fundamental to their child’s outcome. So what was dreamt was of great importance and could, if lucky, predict a scholar as it had for Queen Jin in China. She was the mother of sage-king Wen, author of one of the oldest Chinese texts, the “I-Ching,” or “The Book of Changes.”

In Korea, belief in the receptive and active life of the unborn child in the womb explains why babies are already one year old at birth.

“In ancient days I think this part of the brain was developed that almost everything, their news, they got through their dreams. And they would talk about their dreams when they woke up, at the well.

“I think in part it was (because it was) an isolated country and in the many little villages isolated around the country there was no TV so it was hard to get information,” he explained.

He is particularly interested in the difference between different generations’ dreams, which is why he wanted to capture those of his former students’ parents and grandparents.

Parents, for instance, will have different dreams about their child’s marriage than they will, shaped as they are by attitudes toward the union.

“Dreams are a reflection of life,” said Seligson.

“If you change yourself in your waking life, let’s say you have a habit you want to give up, or a good habit to acquire and you work really hard on that then your dreams will reflect it.”

Many Koreans’ dreams also have cultural resonance.

“What’s really special about the dreams in Korea is so many include the ancestors. The ancestors from the grave, grandfather or grandmother, come and tell them (something).”

Sometimes, ancestors might appear in a dream to tell a relative that it is not yet time to die, other times they may simply be asking them to come and clean up their grave, he said.

Even today though, Seligson believes people should pay attention to their dreams. To help remember them, he recommends leaving an easily accessible notebook by the bed so they can be written down at the earliest opportunity.

“If you establish a relationship with your unconscious then you have a richer dream life and a richer waking life, too,” he said, going on to talk about the lifestyle changes, such as eating more healthily and getting more exercise, he made as a result of his dreams.

“There’s some (dreams) that strike you very strongly that you can’t forget ... they can tell you that something’s going to happen and you better do something about it.”

As Seligson, an enthusiastic council member of the Royal Asiatic Society, has computer elbow and is unable to type, he has enlisted the help of an assistant to help him sift through his stacks of dream records.

Despite being technically retired, the father-of-two is busy trying to draw his life’s work together, which includes another project very dear to him: the “peace train.”

A peaceful soul

In 2002, Seligson awoke recalling a dream where he was traveling through wasteland by train. There was an Israeli woman in the dining car who told him he should work with her because he looked like he knew how to get things done.

When they arrived at their destination, U.S. senators were waiting, congratulating them. In the distance were smoke stacks, surrounded by a sign which read, “peace train.”

Seligson took the dream as an indication of his next step. He feels interpretation is not as helpful if done via books and instead takes a personal approach ― each individual should see their dreams in the context of their lives and experiences.

Soon he was sowing the seeds for an international peace organization, spurred on by the political situation between the two Koreas at the time.

“I said, ‘why should we study English when we’re going to die in a ‘sea of fire’? What about the children? Don’t they have a right to state whether they want to live or die?’” he explained.

So he set about asking 1,000 children in Korea to draw images of peace in their own lives and had them exhibited at the UNESCO Conference on Inter-religious Education and at UNESCO teacher workshops in Seoul.

Through worlddreamspeacebridge.org, the initiative was able to grow and now Seligson travels all over the world ― he has led workshops in countries including Israel, Budapest, Ethiopia and the U.S. ― making metaphorical peace trains of images drawn by children in the schools he visits. Australia is his next destination.

Seligson feels that as well as encouraging children to express themselves in matters that effect their own welfare, it also fosters a peaceful mentality.

“They all have something to draw. They know right away how to draw a picture of peace in their life. And they’re so glad to do it, they get really enthusiastic,” he said, producing some colorful examples in various booklets he has made to give back to them.

“Normally they (children) don’t get that kind of respect. They’re not seen for their potential,” he added, speaking especially of children in developing countries where they can encounter hardship daily.

And it’s not just children he hopes the message reaches: “It shows parents that if they teach their children love and understanding it’s more likely to lead to a safer, more peaceful world.”

Ultimately, Seligson hopes the initiative can be self-generating, and to this end his daughter has set up a Facebook page to help spread his message of peace and create a chain of participating schools.

Another of Seligson’s prophetic dreams saw him wearing a crown which fell around his neck. He took this to mean that he should not take power, hence his passing on of ideas through literature and speeches.

Mind work

As well as working on the peace train and accompanying literature, and on his dream endeavors, Seligson is busy refreshing the poetry he has written.

He finds reading Shakespeare every night helps.

“The next day when I go over the poems my eyes have changed and I can see more clearly because living here for so long, it’s possible to forget what English is supposed to sound like,” he said.

One collection, published last year, is about cherry blossoms. After travelling and studying remote regions of Africa, Asia and Europe from 1972-5, Seligson went to Japan for two years to learn poetry. Based in Kyoto, he made a habit of observing the cherry blossoms each spring and writing about them, and then continued once in Korea.

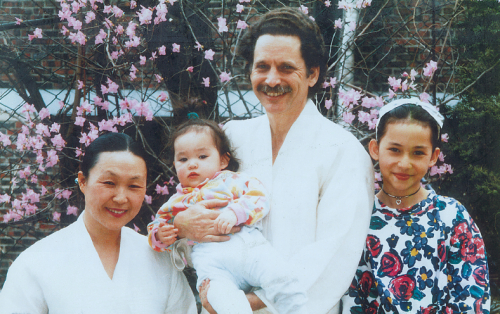

It was in Japan, in fact, that Seligson first made contact with his wife through the exchange of 101 love letters. They were married in 1978, just a few months after his arrival in Korea, and wed at a Buddhist temple on a snowy mountain. The simple ceremony cost just $500.

For a man who has made his life’s work out of the immaterial, and who walks daily in the mountains beside his home near Yonsei University, it seems fittingly romantic.

Every morning and night Seligson does yoga stretches, which he feels is key to health and wellbeing ― both of which are of great importance to him. He became well-acquainted with the practice after trips to India where he studied spiritual texts. His last job was, in fact, as a research fellow in the department of Yoga Studies and Meditation at Wonkwang Digital University.

“What I learned there helped my life so much. I’ve become younger because of them (his students),” he said smiling.

Despite the exciting life Seligson has led up to this point, travelling off the beaten path and writing on obscure topics, he is most inspired by his children.

“I give them so much of my life. I realized that’s the greatest art of all. A child is so much influenced by their parents and we can help shape them into such beautiful beings. That’s even greater art than even poetry.

“They’ve taught me so much, given me so much freedom.”

Fred Jeremy Seligson

● 1945 ― Born in Washington, D.C.

● 1967 ― Awarded a B.A. in International Relations from University of Southern California

● 1970 ― Awarded a Juris Doctor from Indiana University of Law

● 1970-72 ― Served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ethiopia

● 1972-75 ― Traveled and studied remote regions of Africa, Asia and Europe

● 1975-77 ― Learned poetry in Kyoto, Japan

● 1977 ― Arrived in Korea

● 1978-98 ― English professor at Hanguk University of Foreign Studies, collected dreams

● 1983 ― Awarded the Tan-gun Society Poetry Award for Foreigners

● 1989 ― Author of “Oriental Birth Dreams”

● 1999-2006 ― Research fellow at Wonkwang Digital University in the department of Yoga Studies and Meditation

● 2001-present ― On Royal Asiatic Society council

● 2002 ― Author of “Queen Jin’s Handbook of Pregnancy”

● 2002-present ― Initiator of the “peace train” initiative in Korea and beyond

By Hannah Stuart-Leach (hannahsl@heraldcorp.com)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)