Film’s mark on colonial Korea

Scholar’s book introduces fascinating story of movie industry during Japanese colonial period

By Claire LeePublished : Dec. 20, 2012 - 20:00

While local movie buffs now enjoy IMAX theaters and movies rendered in 4-D, watching movies was a different affair about 80 years ago in Seoul.

First of all, people had to endure an “almost unbearable” stench from the theater’s public bathroom, and sometimes, their fellow viewers. The stench and filthiness of the movie theaters became a public hygiene problem in the early 1930s; newspapers published articles warning people not to bring infants to the theaters, as it could seriously risk their health.

Most movies were silent, but people had a different way of enjoying films. Each screening would be accompanied by live music and narration by “byeonsa,” a Korean term for silent film narrator. He would “perform” each and every on-screen action throughout the running time, in front of the viewers.

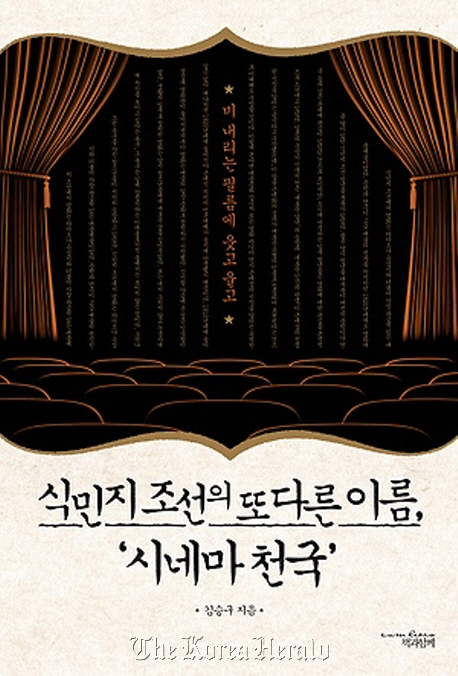

Scholar Kim Seung-koo’s latest book, “Cinema Paradise: Another Name for Colonial Korea,” offers an interesting overview of the local film industry in Seoul during Korea’s colonial period under Japanese rule (1910-1945). According to Kim, it is assumed that movies were first brought to Korea in 1903 or even before, as the oldest surviving newspaper movie ad dates back to June 23, 1903.

First of all, people had to endure an “almost unbearable” stench from the theater’s public bathroom, and sometimes, their fellow viewers. The stench and filthiness of the movie theaters became a public hygiene problem in the early 1930s; newspapers published articles warning people not to bring infants to the theaters, as it could seriously risk their health.

Most movies were silent, but people had a different way of enjoying films. Each screening would be accompanied by live music and narration by “byeonsa,” a Korean term for silent film narrator. He would “perform” each and every on-screen action throughout the running time, in front of the viewers.

Scholar Kim Seung-koo’s latest book, “Cinema Paradise: Another Name for Colonial Korea,” offers an interesting overview of the local film industry in Seoul during Korea’s colonial period under Japanese rule (1910-1945). According to Kim, it is assumed that movies were first brought to Korea in 1903 or even before, as the oldest surviving newspaper movie ad dates back to June 23, 1903.

Movie theaters were first established in Gyeongseong, today’s Seoul, in the 1910s, according to the book. Kim’s research says the theaters were not equipped at all for extreme weather conditions until the 1920s; viewers had to endure extreme heat and cold during summer and winter.

Before talkies were introduced in the 1930s, byeonsa were the stars in the movie scene. Teenagers were more interested in seeing the byeonsa and his performance than the actual film. One of the most popular byeonsa at the time was Seo Sang-ho, who invented his own dance to perform during the screenings. The performers were often accompanied by a small orchestra as well.

But they also frequently faced complaints and absurd requests. Many viewers, who did not understand how film reels roll, would ask the byeonsa to play the film faster when the scene was, in fact, shot in slow motion.

The emergence of talkies did not affect byeonsa at first, according to Kim. Almost all of the films being screened at the time were from Hollywood. Most Korean viewers did not understand English, so they had no choice but rely on a byeonsa’s performance. The narrators disappeared from the scene in the late 1930s, as Japanese subtitles were introduced and viewers wanted to focus on the movie’s original sound rather than the live narration.

Though Japanese films were also imported to colonial Korea, most Korean viewers were offered Hollywood movies, especially in the 1920s, according to the book. There were not many Korean films being made at the time. Japanese films were mostly only screened at Japanese-only theaters, and Koreans were not admitted to these properties. Also, Hollywood became world-famous as the center of the U.S. film industry in the 1920s, and saw a vast expansion of its films. Europe, on the other hand, did not make and export as many films after World War II.

Kim says films, especially those from Hollywood, had a great impact on many Seoulites during Korea’s colonial era.

“Gyeongseong was becoming more urbanized,” Kim writes. “It was natural for urban laborers to seek some sort of entertainment, because they were increasingly pressured and distressed by the workload. Movies provided what they needed, for a relatively cheap price.”

Kim also points out that many male viewers in Gyeongseong were fascinated by the appearance of Hollywood actresses, and enjoyed the films’ salacious sexual imagery. At the time, movie tickets did not have seat numbers, and all seats were first-come, first-served. Many would not leave the venue until the theater closed at around midnight, watching multiple movies; there were no solid rules concerning the number of viewers and seats, and theater staff “felt bad” to kick viewers out just because there weren’t enough seats. According to Kim, this was one of the reasons for the stench and bad hygiene inside the properties.

The look of Hollywood actresses also influenced many local women at the time. According to an essay by writer Ahn Seok-ju published in 1939, a lot of Korean women followed the look of the Hollywood actresses, including the way they wore their socks, makeup, shoes and skirts.

Overall, Kim offers interesting facts and analysis about cinema during Korea’s colonial period, with intelligence and credible research.

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)