North Korea is moving to bolster its relations with Russia as it seeks to court outside assistance to help shore up its crumbling economy and reduce its political and economic dependence on China, which has been ratcheting up pressure over its nuclear program.

The two countries have been expanding political, economic and cultural cooperation in recent weeks. Ranking Russian officials have visited Pyongyang to discuss an ambitious plan to lay a natural gas pipeline through North Korea to the South, while a Russian military band held a rare provincial tour in the reclusive country last week.

Last month, Moscow’s parliament approved a write-off of 90 percent of the $11 billion debt that Pyongyang had amassed since the 1980s.

The upsurge in bilateral exchanges comes at a time of relatively chilly relations between Pyongyang and Beijing, which forged a “blood alliance” during the 1950-53 Korean War. It has gained particular traction ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s two-day trip to Seoul starting Thursday.

A longtime political and economic patron of the isolated ally, China has seen its patience eroded over the years by three nuclear tests, several missile launches and numerous bouts of saber-rattling.

Many diplomats and China experts in Seoul cite Beijing officials as saying that the relationship “isn’t what it used to be,” particularly since the December execution of Jang Song-thaek, leader Kim Jong-un’s once-powerful uncle known for his connections in China.

Beijing has long sought to play down its sway over the Kim dynasty as the West attempts to pressure the defiant regime into giving up atomic weapons by tightening enforcement of U.N. Security Council sanctions and slashing economic incentives.

“In my opinion, it is not right to say that China has a military alliance with North Korea, as it has no such alliance with any other country,” Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Jianchao told visiting South Korean reporters last month.

The two countries have been expanding political, economic and cultural cooperation in recent weeks. Ranking Russian officials have visited Pyongyang to discuss an ambitious plan to lay a natural gas pipeline through North Korea to the South, while a Russian military band held a rare provincial tour in the reclusive country last week.

Last month, Moscow’s parliament approved a write-off of 90 percent of the $11 billion debt that Pyongyang had amassed since the 1980s.

The upsurge in bilateral exchanges comes at a time of relatively chilly relations between Pyongyang and Beijing, which forged a “blood alliance” during the 1950-53 Korean War. It has gained particular traction ahead of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s two-day trip to Seoul starting Thursday.

A longtime political and economic patron of the isolated ally, China has seen its patience eroded over the years by three nuclear tests, several missile launches and numerous bouts of saber-rattling.

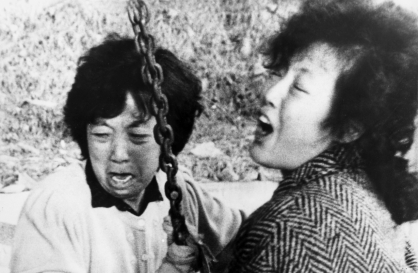

Many diplomats and China experts in Seoul cite Beijing officials as saying that the relationship “isn’t what it used to be,” particularly since the December execution of Jang Song-thaek, leader Kim Jong-un’s once-powerful uncle known for his connections in China.

Beijing has long sought to play down its sway over the Kim dynasty as the West attempts to pressure the defiant regime into giving up atomic weapons by tightening enforcement of U.N. Security Council sanctions and slashing economic incentives.

“In my opinion, it is not right to say that China has a military alliance with North Korea, as it has no such alliance with any other country,” Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Jianchao told visiting South Korean reporters last month.

“This is one of the most important principles upheld by China’s Foreign Ministry. Just like China’s relationship with South Korea, its relationship with North Korea poses no threat to any country.”

For Moscow, a closer relationship with Pyongyang could be a diplomatic swipe at the U.S., which led sanctions over the annexation of Crimea and the ongoing crisis in eastern Ukraine.

It would also provide a boost to Russia’s refocus in Asia, dubbed “Putin’s Pivot,” designed to help counter Washington’s strategic rebalancing toward the region, raise its political and economic clout by nurturing diplomatic ties and expanding energy exports, and court investment to develop Siberia and the Far East.

The North was once a major beneficiary of Russian patronage as a member of the communist bloc. But its partnership with Russia has been marked by regular, ceremonial political exchanges and token gestures of friendly relations dating back to the Cold War era.

Yet the rekindled solidarity would hardly bring about a sweeping shift in Pyongyang-Beijing ties and the geopolitical landscape in the region, officials and experts say. But some observers raised concerns that a Moscow closely aligned with the North may complicate South Korea and U.S. efforts to bring it back to denuclearization talks after a years-long hiatus.

“With North Korea wary of relying too much on China, its attempt to get closer to Russia may rather provide room for Russia to take up a more constructive role, considering its expertise in the nuclear issue and firm opposition to North Korean nuclear weapons,” a senior official at Seoul’s Foreign Ministry said on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

“China, too, wouldn’t think of this as a factor that may change its strategic calculations, at least in the short term, given its massive economic relations with North Korea.”

Recent data showed that though China’s trade with North Korea dropped nearly 3 percent in the second quarter of this year to $1.3 billion, it still accounts for about 90 percent of the reclusive country’s total foreign trade volume.

Stephen Haggard, director of the Korea-Pacific Program at the University of California, San Diego, also said the Pyongyang-Moscow efforts would consist more of geostrategic signaling than economic initiatives and have a limited effect in curbing the North’s dependence on China.

“If there is any good news in the North Korean economy it is due almost entirely to China,” he recently wrote on the blog run by the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“This diversification effort will either fail, because the economy’s tremendous dependence on China is too deep to reverse, or if it ‘succeeds’ the victory will be Pyrrhic, as it will likely signal a contraction of trade altogether.”

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)