[70th Anniversary] After 70 years, S. Korea mulls ‘grand strategy’

‘Projecting clout while mustering support to disarm NK requires “grand strategy,” one that includes steps on Seoul’s dealings with major powers, while avoiding being forced to pick sides.’

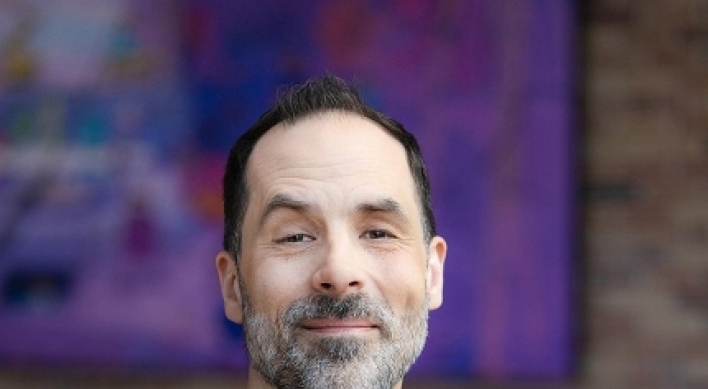

By Choi Si-youngPublished : Aug. 13, 2023 - 17:58

The last 70 years have marked South Korea’s ascent to an economic power able to cope with threats from North Korea, its nuclear-armed neighbor that it has yet to sign a peace treaty with to resolve the 1950-53 Korean War.

Seoul’s postwar efforts had relied on working with the US, the South’s biggest ally. In the early 1960s, aid from Washington accounted for 35 percent of Seoul’s budget and 73 percent of its defense spending. The 1965 agreement the South signed with Japan to restore ties following Japan's 1910-1945 occupation of the peninsula also helped rebuild the economy.

Sending workers to German mines from 1963 and troops to help fight in the Vietnam War in 1965 were other parts of a push to buttress the economy. Loans were secured and local companies expanded business overseas as a result, growing the economy.

The efforts led to a bigger global role for the country. In 1996, South Korea joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. In 1999, it joined the Group of 20, a collection of 20 key industrialized and emerging economies. In 2010, Seoul hosted the G-20 summit, the first for an Asian country and nonmember of the then-Group of Eight, a more select group of the G-20 nations.

The remarkable economic progress, however, has been haunted by ever-growing nuclear threats from North Korea. Pyongyang is expanding its nuclear arsenal, having abandoned the inter-Korean nonproliferation agreement in 1992 and global nonproliferation pact in 2003, known as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The escalating standoff between the US-led alliance of democracies and closer China-Russia ties is rendering the security and economic predicaments trickier to resolve as countries are asked to choose sides.

Addressing global threat

International efforts for North Korea’s disarmament took off in earnest in 2003, when the two Koreas, the US, China, Japan and Russia opened the six-party talks, shortly after the North’s withdrawal from the nonproliferation treaty the same year. Diplomacy has long since stalled. The six parties were close to what some believed was a lasting breakthrough in 2018, when the leaders of the two Koreas met. But ties dipped back the next year.

In December last year, South Korea made a pivot to the three-way US-led coalition on disarmament, unveiling the Indo-Pacific strategy, a “watershed” in South Korean history according to its foreign minister. The three partners -- South Korea, the US and Japan -- place priority on sanctions over diplomacy.

The foreign policy, a doctrine promoting “freedom and democracy,” came at a time when Seoul, like most countries, finds itself having to pick a side between the US and China amid their escalating rivalry, which some liken to a “new Cold War.” Beijing is at unease with Seoul over the initiative, urging the South to “respect other countries.”

Priorities ahead for Seoul

Bolstering the US-led coalition is expected to be the priority for the Yoon administration, which took power in May last year, vowing closer ties with Washington and Tokyo. Yoon’s decision to put behind historical disputes that had plunged Seoul-Tokyo ties to a record low has led to ever closer three-way cooperation.

The three countries’ leaders will meet at the Camp David retreat in Maryland on Friday. Whether the gathering could lay groundwork for a trilateral security arrangement remains to be seen.

“That’s (the security pact) a bit premature at the moment, but I’d say it’s ultimately in the right direction,” said Shin Kak-soo, South Korea’s former vice foreign minister.

Shin, who later served as ambassador to Japan, underscored “taking things at the right pace,” saying the three partners would have to build trust to shake hands on something as binding as a security pact.

Park Won-gon, a professor of North Korean studies at Ewha Womans University, said institutionalizing a permanent three-way consultation will help start that long process. According to Yoon officials, talks are underway to make that happen, though they note that the three leaders would have to decide on details themselves.

“We’ll have to see but the chances of Korea doing something to immediately prompt intense protest from China or Russia aren’t high, even if it backs a permanent trilateral meeting with the US and Japan,” Park said of criticism that trilateral cooperation could anger Beijing and Moscow.

Seoul plans to resume regular three-way summits with Japan and China as this year’s host, after a four-year hiatus prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. That meeting could be an opportunity for Seoul to engage both the US and China, Park added.

But some experts contend such a parallel push could be superficial and even unsustainable if policymakers in the South don’t figure out a more holistic approach to policy on Washington, Beijing and Moscow.

Balancing ties

“A stronger three-way coalition is unavoidable in the face of growing nuclear threats from North Korea. I’m not saying we reverse that,” said Wi Sung-lac, who served as South Korea’s chief nuclear envoy on North Korea during the right-wing Lee Myung-bak administration and later as ambassador to Russia.

The Yoon administration offers a clear blueprint on the way it wants to deal with the US and Japan, but no such plans seem to be in place for Beijing and Moscow, Wi said. He argues that just as much diplomacy should take place with the two to prevent their closer ties with Pyongyang. China and Russia, two permanent United Nations Security Council members, often block attempts at sanctioning the North.

“I’m talking about an integrated, long-term strategy that places priority on the US while leaving some room for China and Russia. We don’t have that now, because we have only quick fixes,” Wi said, referring to recent spats Seoul had with both of them.

In June, South Korea and China called in each other’s top envoy in a tit-for-tat spat over the Chinese ambassador’s public warning Seoul’s pro-US policies could bring it harm. Seoul and Beijing are still at odds over the South’s potential backing for Taiwan, a self-ruled democratic island Washington supports. Beijing claims it could take back the island by force if necessary.

Meanwhile, Russia warned Korea over Yoon’s conditional offer of military support for Ukraine. That did not stop the Korean leader from making a surprise tip last month to Ukraine’s capital Kyiv, a move some experts see as reinforcing a push to align Seoul with a tighter Western coalition decrying Russia’s war in Ukraine.

“If we need something in return from someone, we need to find the ‘right tone’ on the issue someone wants resolved,” said Chung Jae-hung, director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the Sejong Institute. “So we need policy change on the Taiwan and Ukraine issues.”

Hong Wan-suk, head of Russian and CIS studies at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, said Russia is serious about bolstering ties with North Korea, citing a Russian delegation that visited Pyongyang for the July 27 celebrations. That’s a holiday on which the North marks what it calls victory against the US-led UN forces in the 1950-53 Korean War.

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, who led the mission, held talks with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un -- the first high-level dialogue for Pyongyang since the COVID-19 pandemic started in early 2020. The two countries touted their ties.

‘Grand strategy’

Projecting global clout while mustering international support to disarm North Korea requires a “grand strategy,” one that includes concrete steps on Seoul’s dealings with major powers, while avoiding being forced to pick sides in the US-China rivalry, said Chun Chae-sung, a professor of political science and international relations at Seoul National University.

“We need a coherent policy on US-China relations and also on North Korea. The former is more urgent because that’s more crucial to our own survival,” Chun said of the Yoon administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy, a plan that he said has yet to be fleshed out.

Nothing is too late, Chun added, saying that Washington and Beijing are themselves still in the process of adjusting policy on each other, with many countries also undecided on how they should approach the US-China competition.

“At least, we’re going in the right direction. We just need more coordinates, and we need them fast,” Chun said.

![[Music in drama] Rekindle a love that slipped through your fingers](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/01/20240501050484_0.jpg&u=20240501151646)

![[New faces of Assembly] Architect behind ‘audacious initiative’ believes in denuclearized North Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/01/20240501050627_0.jpg&u=20240502093000)

![[KH Explains] Will alternative trading platform shake up Korean stock market?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/01/20240501050557_0.jpg&u=20240501161906)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids go gold in US with ‘Maniac’](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/05/02/20240502050771_0.jpg&u=)