[Visual History of Korea] Ancient art of traditional calligraphy

By Korea HeraldPublished : Aug. 6, 2022 - 16:00

Civilizations are judged by the quality of historical knowledge they document and leave behind.

For about 3,000 years, “seoye,” the art of calligraphy, has been a visible documentation of East Asian civilizations and culture.

The ink used in traditional calligraphy, “meok,” made from burnt carbon, is long-lasting.

In traditional calligraphy, each brush stroke carries philosophical thoughts beyond just the literal meaning of the written characters.

For example, a dot represents heaven, while a horizontal line across represents the land. The vertical brush stroke represents the person.

There have been scores of prominent calligraphers and a vast number of talented calligraphers throughout history.

For about 3,000 years, “seoye,” the art of calligraphy, has been a visible documentation of East Asian civilizations and culture.

The ink used in traditional calligraphy, “meok,” made from burnt carbon, is long-lasting.

In traditional calligraphy, each brush stroke carries philosophical thoughts beyond just the literal meaning of the written characters.

For example, a dot represents heaven, while a horizontal line across represents the land. The vertical brush stroke represents the person.

There have been scores of prominent calligraphers and a vast number of talented calligraphers throughout history.

Studying seoye, in all of its various styles, is a lifelong commitment to unending learning.

Using Hanja characters in traditional calligraphy is an act steeped in meticulous traditions.

“Seonbi,” traditional scholars, are said to have four friends in their studies: a brush, black ink stone, ink stone grinding tray and mulberry paper.

Korea produced some of the best quality ink stones and paper.

Historical records kept in neighboring kingdoms mention importing large orders of ink stones and mulberry paper from the Silla Kingdom (57 BC – AD 935).

Korean paper, originally called “gyelimji,” came to be known as “goryeoji” during the Goryeo period, then “joseonji” during the Joseon era, before being called “hanji” in modern times.

During the Goryeo period, when there was active international trade across the West Sea, paper and ink stones from Goryeo were in high demand in the Yuan dynasty China on the other side of the water.

Ink stones are made from burnt pine tree roots.

When the world’s oldest woodblock printed paper was found inside the Sakyamuni Pagoda time capsule during renovation in 1966, researchers investigated mulberry paper on which the Pure Light Dharani Sutra was printed. The paper made with mulberry tree fiber was found to be from the Silla period.

The Pure Light Dharani Sutra was printed some 1,300 years ago, sometime between 704 and 751, when the Sakyamuni Pagoda of the Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province, was built.

The amazing longevity of meok and the paper on which the ink is used is an enduring attraction of traditional calligraphy.

While Goryeo published printed books with movable metal printing types in the early 13th century, calligraphy using a brush on mulberry paper proliferated as a genre of artistic expression.

For example, a traditional cursive script in calligraphy called “choseo” looks nothing like the original Hanja characters.

“The choseo cursive script is called the flower of the Hanja characters. It has infinite variations, and calligraphy best reflects a person’s thoughts,” said the late Kim Tae-gyun, who headed the Byeongsanseowon Confucian Academy, in Yeongju, North Gyeongsang province.

Using Hanja characters in traditional calligraphy is an act steeped in meticulous traditions.

“Seonbi,” traditional scholars, are said to have four friends in their studies: a brush, black ink stone, ink stone grinding tray and mulberry paper.

Korea produced some of the best quality ink stones and paper.

Historical records kept in neighboring kingdoms mention importing large orders of ink stones and mulberry paper from the Silla Kingdom (57 BC – AD 935).

Korean paper, originally called “gyelimji,” came to be known as “goryeoji” during the Goryeo period, then “joseonji” during the Joseon era, before being called “hanji” in modern times.

During the Goryeo period, when there was active international trade across the West Sea, paper and ink stones from Goryeo were in high demand in the Yuan dynasty China on the other side of the water.

Ink stones are made from burnt pine tree roots.

When the world’s oldest woodblock printed paper was found inside the Sakyamuni Pagoda time capsule during renovation in 1966, researchers investigated mulberry paper on which the Pure Light Dharani Sutra was printed. The paper made with mulberry tree fiber was found to be from the Silla period.

The Pure Light Dharani Sutra was printed some 1,300 years ago, sometime between 704 and 751, when the Sakyamuni Pagoda of the Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province, was built.

The amazing longevity of meok and the paper on which the ink is used is an enduring attraction of traditional calligraphy.

While Goryeo published printed books with movable metal printing types in the early 13th century, calligraphy using a brush on mulberry paper proliferated as a genre of artistic expression.

For example, a traditional cursive script in calligraphy called “choseo” looks nothing like the original Hanja characters.

“The choseo cursive script is called the flower of the Hanja characters. It has infinite variations, and calligraphy best reflects a person’s thoughts,” said the late Kim Tae-gyun, who headed the Byeongsanseowon Confucian Academy, in Yeongju, North Gyeongsang province.

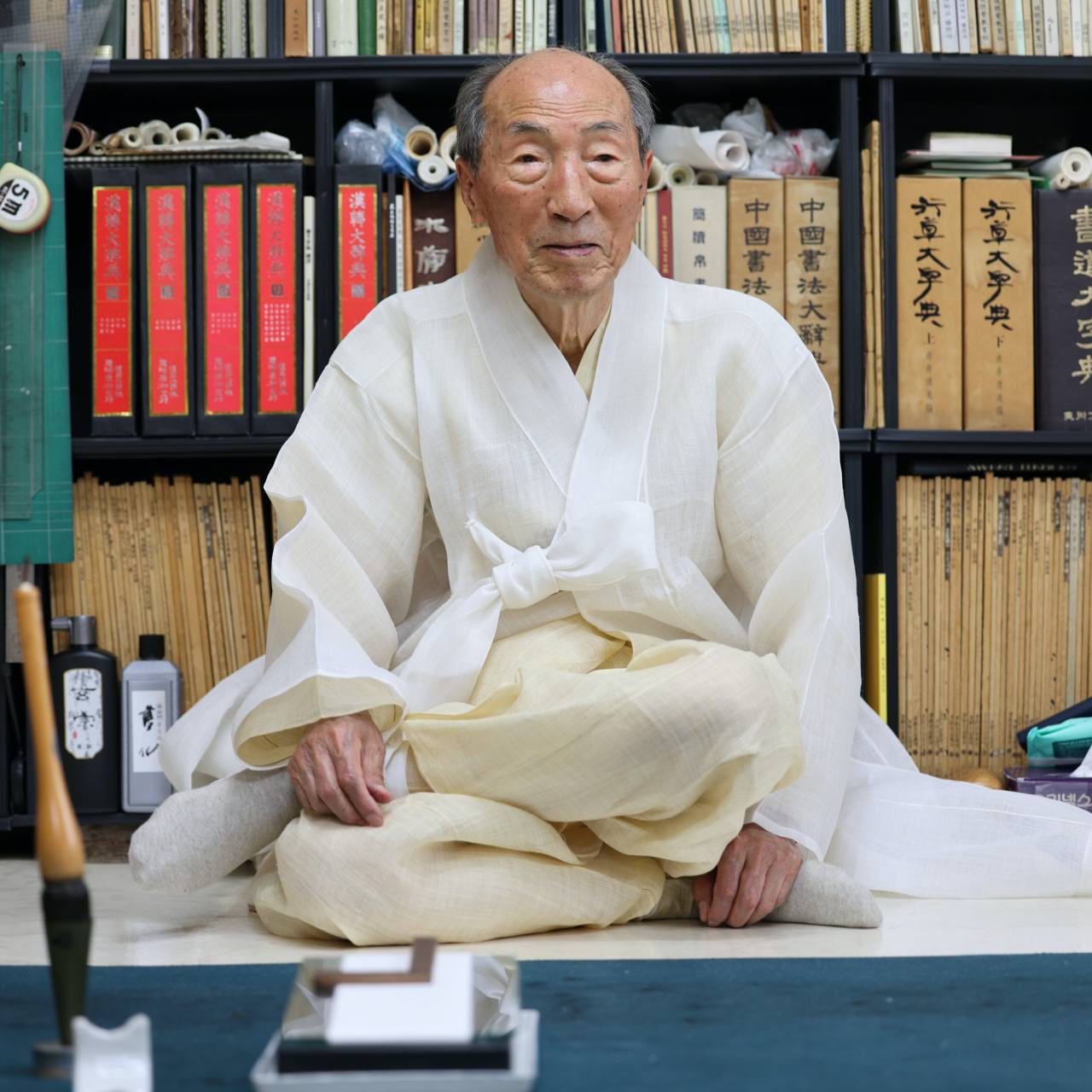

Kim started calligraphy at an early age by learning from his village elders. He became one of the most preeminent authorities in Korean calligraphy and taught at universities. He passed away July 19, according to his wife, Rhie Myin-zha, a retired professor. He was 88.

Kim was a modest man of very few words and lived a life of quiet seclusion.

I was privileged to have documented Kim working with his seemingly effortless brush strokes.

During the interview, Kim said, “I have not produced a piece with which I’m completely satisfied yet.”

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

---

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed

Kim was a modest man of very few words and lived a life of quiet seclusion.

I was privileged to have documented Kim working with his seemingly effortless brush strokes.

During the interview, Kim said, “I have not produced a piece with which I’m completely satisfied yet.”

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

---

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)