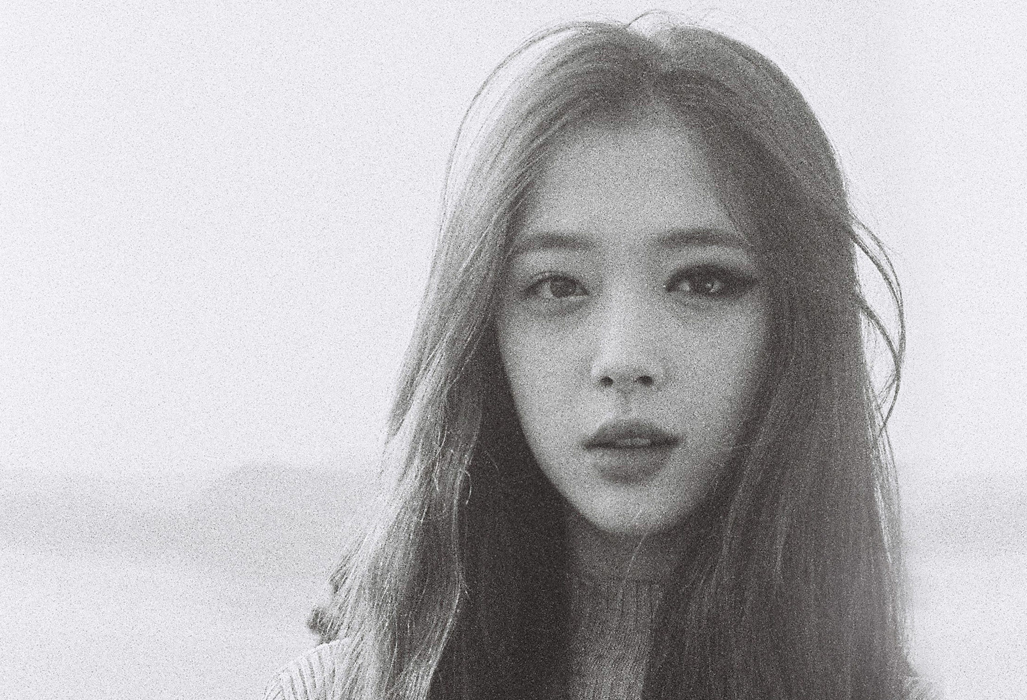

[Feature] Sulli’s death sparks soul-searching on misogynistic culture, journalism ethics

Calls grow for internet real-name system, anti-discrimination law and reflection on journalism ethics

By Ock Hyun-juPublished : Nov. 3, 2019 - 15:01

When 25-year-old Korean singer and actress Sulli was found dead at her home last month, it was described as “murder by fingertips.”

Sulli, whose real name was Choi Jin-ri, had long been the target of online vitriol for defying the country’s social norms -- from wearing a shirt without a bra in public and being candid about her romantic relationships to livestreaming a drinking session with friends.

The former member of top Korean girl group f(x) also came under attack from online trolls for speaking out on mental health issues, cyberbullying and advocating women’s rights to abortion, all of which remain sensitive topics in Korean society.

Sulli had been suffering from severe depression, according to police.

On top of high pressure and intense competition that K-pop stars face from an early age, Sulli’s death has exposed the dark side of a society that has long tolerated cyber insults and hatred against female entertainers, as well as reckless reporting on celebrities’ private lives, experts say.

Following Sulli’s death, a number of bills aimed at curbing cyberbullying have been submitted to the National Assembly, despite concerns over violations of free speech.

Calls are also mounting for reflection on journalism ethics and for the enactment of an anti-discrimination bill that could outlaw hate expressions in public.

Sulli, whose real name was Choi Jin-ri, had long been the target of online vitriol for defying the country’s social norms -- from wearing a shirt without a bra in public and being candid about her romantic relationships to livestreaming a drinking session with friends.

The former member of top Korean girl group f(x) also came under attack from online trolls for speaking out on mental health issues, cyberbullying and advocating women’s rights to abortion, all of which remain sensitive topics in Korean society.

Sulli had been suffering from severe depression, according to police.

On top of high pressure and intense competition that K-pop stars face from an early age, Sulli’s death has exposed the dark side of a society that has long tolerated cyber insults and hatred against female entertainers, as well as reckless reporting on celebrities’ private lives, experts say.

Following Sulli’s death, a number of bills aimed at curbing cyberbullying have been submitted to the National Assembly, despite concerns over violations of free speech.

Calls are also mounting for reflection on journalism ethics and for the enactment of an anti-discrimination bill that could outlaw hate expressions in public.

‘Sulli laws’

Following Sulli’s death, the presidential office website was flooded with petitions demanding users be required to register their real names before commenting. The petitions also called for heavier punishments for online trolls and media outlets that spread falsehoods.

According to a Realmeter poll conducted after Sulli’s death, nearly 70 percent of Koreans supported the adoption of the internet real-name online comment system, while 24 percent opposed it.

The public outcry led Daum, the country’s No. 2 portal site, to temporarily close its comments sections under entertainment news through which cyber insults frequently occur.

Against this backdrop, two bills aimed at stamping out online abuse were introduced at the National Assembly on Oct. 25.

Rep. Park Dae-chul of the Liberty Korea Party submitted a bill requiring online users to reveal their online user name and IP address -- a numeric designation to identify a physical location on the internet -- when posting comments on portals such as Naver and Daum.

The portals are a major platform of news consumption in Korea and allow users to comment anonymously.

Another bill presented by Rep. Park Sun-sook of the minor opposition Bareunmirae Party targets such portals by requiring them to filter out malicious, discriminatory and hateful comments, and to block people online from posting such comments.

“The online platforms became a rubbish bin for anger and raw emotions for many Koreans. They just don’t see the suffering they inflict on victims with a simple, short comment,” said Kwak Geum-joo, a psychology professor at Seoul National University.

“They even feel a sense of unity and belonging because so many people leave such malicious comments,” she said. “They don’t feel guilty and even think they are just and right.”

Drastic measures such as the internet real-name system are necessary to stop them from hurting others behind an online pseudonym even in the short term, she added.

The internet real-name system, however, was already declared unconstitutional in 2012.

The Constitutional Court ruled against a similar law on the internet real-name system, which required Koreans to use their real names on websites, in a unanimous decision, citing restrictions on the freedom of speech.

Son Ji-won, a lawyer for Open Net Korea, questions how effective the internet real-name system could be in rooting out the widespread cyberbullying.

“People who leave malicious messages are not concerned about revealing their identity, if you look at social media,” Son said. “Online trolling happens not because we don’t have the internet real-name system, but because of society’s hate culture and low public awareness about human rights.”

Such a system would only discourage people from criticizing the powerful and stifle minorities’ opinions because of fears they would be punished, she noted.

“Despite the side effects, online anonymity is crucial to those who want to challenge unfair systems, political and economic powers, as well as minorities such as women and sexual minorities (seeking to stand up for their rights),” she said.

Misogynous culture, media’s role

What pushed Sulli was not just cyberbullying, but also the online culture where hate speech against women is prevalent, as well as the media phenomenon of “clickbaiting,” experts point out.

According to a survey on 1,200 adults by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, which was conducted in March, 64.2 percent of respondents said they had been subject to hate speech. The biggest target of hate speech was a person from a certain region (74.6 percent), followed by women (67.8 percent) and sexual minorities (67.7 percent.)

“Sulli’s provocative remarks, which were not expected from a female K-pop star, drew more misogynic comments and criticisms,” Yoon Kim Ji-yeong, a professor at the Institute of Body and Culture at Konkuk University, said. “Such comments typically accuse female stars of being slutty and cheap, which does not really apply to male stars.”

Sulli was rare among K-pop stars in that she vocally expressed her views on women’s rights in the public sphere, upending the entertainment industry’s expectations that they stay silent about their private lives or on divisive issues and remain “pure,” obedient and sexually desirable.

When Sulli publicly expressed her support for the pro-choice movement and defended her decision not to wear a bra, she instantly became the target of anonymous misogynous comments.

“There should be some standards on what constitutes misogyny and hatred, why it should be banned, and introduce bills that can regulate it,” Yoon said.

For now, Korea has no law banning discrimination or inflammatory remarks in public.

The NHRCK receives complaints and investigates when discrimination takes place, but it holds no legally binding force.

Several anti-discrimination bills aimed at rooting out bigotry on such grounds as gender, disability and race have been submitted to the National Assembly since 2007, but they have never passed through the parliament due to strong resistance.

Yoon also pointed out that the entertainment industry commercializing female stars’ sexuality as well as the media frenzy inducing hate comments need to be addressed together.

Unfounded rumors that haunted Sulli were often picked up by news outlets and were further spread through media. When a controversy surfaced, news outlets would again report on the controversy, inviting more hateful comments and generating more online traffic.

“The press played a role in creating a cycle of producing and amplifying gossip, prejudice and malicious comments,” said Choi Jin-bong, a media communications professor at Sungkonghoe University.

“While the freedom of press must not be controlled, media outlets themselves should establish a system that can monitor and filter out gossip-mongering and provocative contents,” he said.

(laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Ock Hyun-ju

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)