[Multicultural Korea] Local subsidies encourage foreign ‘bride buying’

Rural counties offer men marrying foreign brides money to defray costs

By Kim Bo-gyungPublished : Feb. 18, 2019 - 16:24

The number of foreign residents in Korea continues to grow and now accounts for some 3.6 percent of the country’s population. This story is part of a series that examines how Korea is grappling with the issue of multiculturalism, as well as the challenges facing new arrivals. -- Ed.

Raising a rural population that has been declining for come 30 years has long been near the top of the government agenda, with some municipal governments resorting to helping pay for foreign brides.

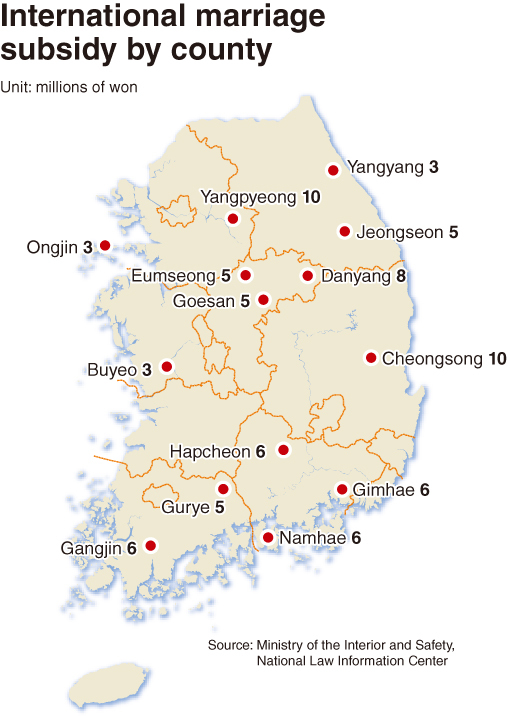

Over 35 municipal governments that depend on the agriculture and fisheries industries have implemented bylaws providing marriage subsidies to local men who tie the knot with foreign brides, raising concerns among experts on government-led measures that encourages them to “purchase” brides from outside the country, generally from Southeast Asia, to increase the population and stem the rural exodus.

Ranging from 3 million won to 10 million won ($2,670-$8,900), depending on the municipal government, the subsidies serve one purpose: halt the steep decline in population in rural regions by supporting Korean bachelors who have struggled to find a wife by looking overseas.

This year, the highly controversial marriage subsidies are offered by over 35 municipal governments that have been faced with decreasing population since the 1980s as a result of urbanization.

Yangpyeong County in Gyeonggi Province, for instance, provides 10 million won to local men between the ages of 35 and 55 working in the agriculture, fisheries, and forestry industries who have never been married and have lived in the area for more than three years.

Since Yangpyeong County adopted the bylaw in 2009, 57 people have received funds to date out of 570 multicultural households registered in that period. Most of the brides were from Vietnam, followed by other Southeast Asian countries, the county said.

Though the program targets men, it is overseen by an official in charge of welfare for women at the county’s gender equality and family team.

Raising a rural population that has been declining for come 30 years has long been near the top of the government agenda, with some municipal governments resorting to helping pay for foreign brides.

Over 35 municipal governments that depend on the agriculture and fisheries industries have implemented bylaws providing marriage subsidies to local men who tie the knot with foreign brides, raising concerns among experts on government-led measures that encourages them to “purchase” brides from outside the country, generally from Southeast Asia, to increase the population and stem the rural exodus.

Ranging from 3 million won to 10 million won ($2,670-$8,900), depending on the municipal government, the subsidies serve one purpose: halt the steep decline in population in rural regions by supporting Korean bachelors who have struggled to find a wife by looking overseas.

This year, the highly controversial marriage subsidies are offered by over 35 municipal governments that have been faced with decreasing population since the 1980s as a result of urbanization.

Yangpyeong County in Gyeonggi Province, for instance, provides 10 million won to local men between the ages of 35 and 55 working in the agriculture, fisheries, and forestry industries who have never been married and have lived in the area for more than three years.

Since Yangpyeong County adopted the bylaw in 2009, 57 people have received funds to date out of 570 multicultural households registered in that period. Most of the brides were from Vietnam, followed by other Southeast Asian countries, the county said.

Though the program targets men, it is overseen by an official in charge of welfare for women at the county’s gender equality and family team.

“This form of marriage is basically bride-buying -- marriage based on money rather than love,” said Jang Han-up, director of the Ewha Multicultural Research Institute.

“Such an approach to shopping-like marriage leads to linguistic barriers and human rights problems. They (foreign brides) are vulnerable to human rights abuses, treated as property and expected to take the role of a housekeeper and a sexual object.”

According to a National Human Rights Commission of Korea survey of 920 women marriage migrants, 42.1 percent replied they had experienced domestic violence and 68 percent had experienced unwanted sexual advances.

The international marriage subsidy partially covers marriage expenses, including airfares, accommodations and brokerage fees, among others. Upon selecting a number of candidates on a matchmaker’s online website, Korean men typically fly to the country to meet the women in person.

Marrying women from Uzbekistan is most expensive, costing an average 18.3 million won, or $16,200, per person, followed by the Philippines at 15.2 million won, Cambodia 14.4 million won, Vietnam 14.2 million won and China 10.7 million won, according to a 2017 study conducted by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family on international marriage matchmaking business.

Among international marriages between Korean men and foreign women, brides from Vietnam accounted for 73 percent, and it took an average 3.9 days from the couple’s first meeting to the walk down the aisle.

In terms of age, Korean grooms averaged 43.6 years old and foreign brides 25.2, showing an average age difference of 18.4 years, according to the research.

“You rarely see older single women here. Most women are married or have moved to the city for work and gotten married there. The program was made for male farmers who are unable to find a spouse on their own,” a Yangpyeong County official said, attributing their hardship to financial instability.

“Most Korean women refuse being set up with Korean men (in rural areas), who ultimately settle with marriage migrant women. So we want to help them find a spouse,” an official at a county in Gyeonggi Province, who wished to remain anonymous, said.

As Korea began its rapid economic ascent in the 1960s, a significant number of women in rural areas flocked to the cities for factory jobs to financially contribute to their families. Limited job opportunities on farms also attributed to the rural exodus.

Men, on the other hand, generally had a higher tendency to remain on the farm due to Confucianism that obligated them to continue the family name and business and look after parents.

In this age of gender equality and globalization, the country’s adherence exclusivism and male-oriented culture is reflected in international marriage subsidies.

Article 1 of South Gyeongsang Province’s marriage fund ordinance, “International Marriage Support Ordinance for Bachelors in Rural Regions” states the purpose of the fund as being to arrange international marriage and offer partial marriage expenses for bachelors in the rural areas to boost the drive for farming by helping them form a family.

“Such ordinances are problematic. A public policy should not target a narrow group of people. Marriage migrant women enter South Korea via marriage because they don’t have any other options. This also means the Korean society isn’t willing to accept migrants unless they are committed to marriage and giving birth,” said professor Cho Hye-ryeon of the Korean Institute for Gender Equality Promotion and Education.

“It is about time South Korea reviews its policies and views on marriage migrant women and moves toward embracing them as members of society rather than limiting their boundaries to the family. To do so, the country’s overall family-centered policies should shift to support and respect individuals,” Cho added.

A vast majority of migrant women, who have likely first encountered Korea via flashy K-pop groups and glamorous Korean dramas on TV, relocate here with dreams of living a different life and to financially support their family back home.

“The agency has previously conveyed its opinion to the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family that it is inappropriate for the government to support such international marriage,” said Lim Sun-young, an official who oversees migrants’ rights at the National Human Rights Commission of Korea.

To make sure international couples remain in the region, Yangyang County in Gangwon Province stipulates in the ordinance for couples to return the subsidy of 3 million won in such a case of divorce or relocation within a year into marriage.

By Kim Bo-gyung (lisakim425@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] No more 'Michael' at Kakao Games](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050183_0.jpg&u=20240428180321)

![[Grace Kao] Hybe vs. Ador: Inspiration, imitation and plagiarism](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050220_0.jpg&u=)