[HERALD INTERVIEW] ‘US-China clash could reset inter-Korean ties’

By Korea HeraldPublished : Jan. 16, 2017 - 17:25

With US President-elect Donald Trump amplifying his pugnacious rhetoric on China, foreign policy pundits have sounded their jitters about the fallout on the Korean Peninsula and North Korean nuclear impasse.

While cooperation between the US and China has generally expanded diplomatic room for South Korea and vice versa, the coming clash of the two titans is “not necessarily a bad thing,” according to John Delury, associate professor at Yonsei University’s Graduate School of International Studies.

The renowned historian of modern China and North Korea told The Korea Herald that Seoul could carve out its strategic niche in the US-China rivalry, by capitalizing on economic openings and harnessing “smart” strategies in security.

Instead of only focusing on sanctioning Pyongyang, Seoul could encourage the communist country to develop its economy through “developmental dictatorship,” similar to the way China has opened and reformed its market since 1978, he argued. The following is an excerpt from the interview.

While cooperation between the US and China has generally expanded diplomatic room for South Korea and vice versa, the coming clash of the two titans is “not necessarily a bad thing,” according to John Delury, associate professor at Yonsei University’s Graduate School of International Studies.

The renowned historian of modern China and North Korea told The Korea Herald that Seoul could carve out its strategic niche in the US-China rivalry, by capitalizing on economic openings and harnessing “smart” strategies in security.

Instead of only focusing on sanctioning Pyongyang, Seoul could encourage the communist country to develop its economy through “developmental dictatorship,” similar to the way China has opened and reformed its market since 1978, he argued. The following is an excerpt from the interview.

The Korea Herald: What is your forecast for US-China relations this year and their implications on the Korean Peninsula?

John Delury: It looks like US-China relations are in for a rocky year. President-elect Donald Trump has waved the red cape at the Chinese bull through his tweets, going for the jugular that is Taiwan. That was very surprising to the China-watching community. As Trump has vowed to upend the US’ trade relationship with China, the appointment of his China team also looks hard-line. Chinese experts say the country is bracing for a storm.

For South Korea, this is not necessarily bad news. The key is to have a strategy in adjusting to the turbulent changes. Seoul could turn the US-China competition to its advantage, or at least mitigate the downsides. If the US and China start a trade war, there will be financial chaos, but also new opportunities. If China retaliates against the US and shuts off part of its trade relationships, it could create openings for Korean companies in the Chinese market. If Washington and Beijing are locked in an aggravated security situation, Seoul could play a bridging role as an honest broker. There shouldn’t be an automatic assumption that the US-China conflict would spell disaster for South Korea.

KH: How do you foresee Trump’s foreign policy stance, particularly on security and China?

Delury: Trump has appointed many military people in foreign policy and defense. It seems that Trump wants to be an isolationist and doesn’t want to embroil the US in quagmires like Iraq and Afghanistan. At the same time, he has shown nationalistic and hawkish tendencies, talking tough and asserting America’s strength. There is a contradiction between his isolationism and nationalism, and it’s unclear how these two will play out. There are flashpoints awaiting for the fuse to light them off, most notably in the cross-straits relations, South China Sea and North Korea.

KH: If Trump disengages US military commitment on the Korean Peninsula, will it make it more difficult for Seoul to counter North Korean threats? Will Seoul have to play a more active role in the possible vacuum of US influence?

Delury: The possibility of Trump pulling back security commitment from the alliance doesn’t have to be a bad thing for South Korea. As Seoul annually spends on its military $36.4 billion -- 2.6 percent of its gross domestic product and roughly the same amount as North Korea’s economy -- it is more than capable of deterring the North. To counter Pyongyang’s asymmetrical threats, Seoul could strengthen its “smart” deterrence.

Issues like the operational control transfer and burden sharing can move the South toward a greater defense autonomy. It could balance out the nature of its military so that the different branches are equally well developed. It could raise questions like “do we really need a gigantic military,” or “do we need universal conscription?”

South Korea standing on its own militarily could also create positive opportunities for the inter-Korean relations. One of North Korea’s foreign policy tenets is that they can’t sit as South Korea’s equals, because the South is sitting on the US’ shoulders. So Pyongyang says to Seoul, “we really want to talk with you about the nuclear issue, but it’s really between us and the US, because you are under their nuclear umbrella.”

Whereas this ends the conversation, if Seoul becomes more autonomous, with smart strategies to decrease tensions with Pyongyang, it could benefit everyone, including the US. The American taxpayers do not need to subsidize the defense of South Korea. Dealing with these issues will be critical to the next South Korean leadership.

KH: What is your view of Washington’s “strategic patience” on the North Korean nuclear conundrum? What should the Trump administration do?

Delury: Many Chinese have been waiting for a policy change in Washington and Seoul. Trump might be different from Obama in ending the “strategic patience.” The big question is how delusional it is to think of denuclearization at this point. There is no short term scenario where Kim Jong-un would give up his nuclear deterrent. Rationally speaking, he shouldn’t. The DPRK (North Korea) is not secure enough in the region or in the world to yield the program.

The right strategy should be to gradually change our relationship with Pyongyang, so that 10 to 20 years down the road, whoever is in power in North Korea can say that “we don’t need nuclear bombs anymore, because they hinder our abilities in diplomacy, trade and investment.” Denuclearization is a very long-term proposition, a decadeslong goal. In the meantime, we need to lower the tensions and risks, improve security relations and trust, and build North Korea’s economy by working with Kim Jong-un, not against him.

One of the first priorities of Trump’s administration should be a deal on a “cap and freeze” on nuclear weapons and resuming the International Atomic Energy Agency inspections, so that we know more about what is going on inside the Hermit Kingdom. Due to the absence of diplomacy over the last eight years, there’s so much in the dark. The “complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization” should not be in everyone’s minds in near future.

KH: As Beijing increases its ascendance in the world and in Asia in particular, toward the “G-2” and “new type of great power relations,” where does North Korea fit in? Is Pyongyang becoming more of a burden on China that is a rising regional hegemon?

Delury: Some Chinese scholars say that Pyongyang is becoming increasingly burdensome to Beijing, which is expected to play a more responsible role within the international community. But they are not the mainstream, representing their own views rather than the official policy.

Beijing’s policies toward the Korean Peninsula and North Korean nuclear conundrum have been almost painfully consistent: to get along with both Koreas. This implies the existence of a divided peninsula, which is fine by Beijing.

The Chinese repeat over and over again, “denuclearization and peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula by means of dialogue and negotiation.” By dialogue they mean negotiations between Pyongyang and Washington, which is difficult to implement, because the North is hell-bent on holding onto their nuclear deterrent, and America is little interested in peaceful negotiations. Whereas Americans think that either sanctions or a regime collapse is the solution, most Chinese do not think North Korea must inevitably collapse.

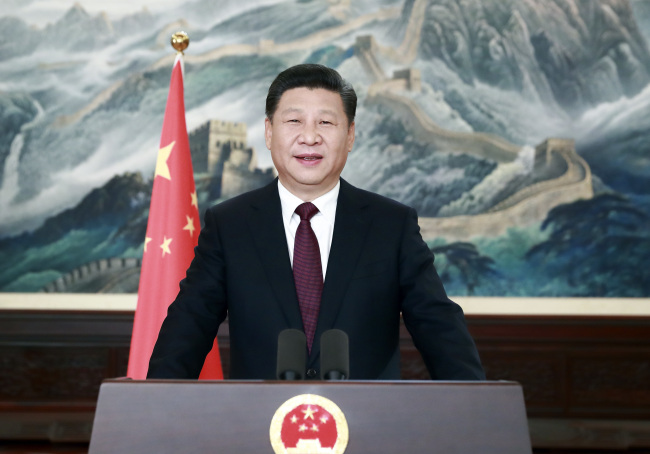

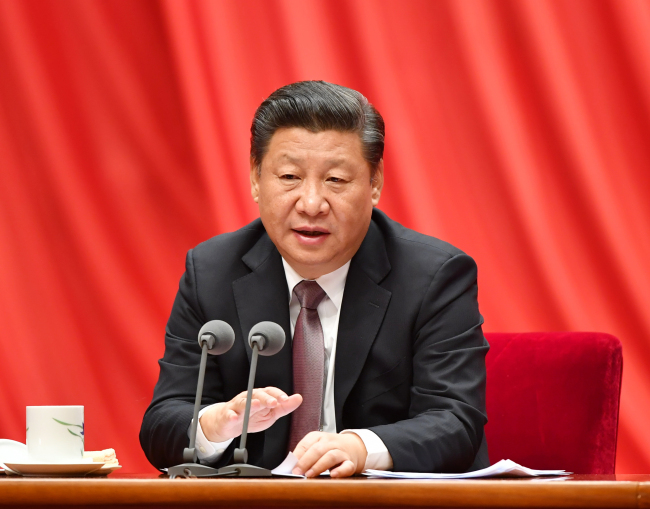

China’s rise and Xi Jinping’s “new type of great power relations” have had a negligible effect on the status quo on the peninsula. As North Korea values its independence more than anything else, an ever more assertive China is a threat to the regime. Kim Jong-un is more resistant to Xi Jinping than his father was to Hu Jintao or Jiang Zemin.

KH: How credible has been Beijing’s implementation of the United Nations Security Council sanctions 2321 as well as the previous 2270, encompassing secondary boycott and strict curbs on Pyongyang’s export of coal?

Delury: It is my view that China is careful to abide by the strict interpretation of UNSC resolutions. They want to maintain the status of a responsible member of the UNSC, a pillar of Chinese diplomacy. They are also frustrated with Kim Jong-un and his constant improvement of the nuclear program. Beijing will apply some level of punitive sanctions at the UN level.

All that said, the Chinese do not believe that sanctions will change Pyongyang’s strategic calculus. To the Chinese, the sanctions are like a slap on the wrist, with each slap getting harder. But ultimately it cannot denuclearize North Korea, and they don’t expect it to. They are probably right. There have been eight years of steadily increasing sanctions, but Pyongyang’s investment in nuclear and missile capabilities has equally increased.

Short of completely shutting the border between the two countries and causing North Korea to collapse, these rounds of sanctions are not having a fundamental impact on the problem. Sanctions could even be counterproductive in the sense that they intensify North Korea’s sense of insecurity, which is why it desperately hangs onto its nuclear program.

The issue with 2270 was on the coal loophole and livelihood exemption conditions. Like a game of whack-a-mole, the goal of the latest 2321 was to close these loopholes. But this misses the bigger picture, which is that China is committed to the notion that sanctions should not cut off the North Korean economy or devastate the livelihood of North Korean people.

KH: What is your view on the utility of the six-party talks involving the US, China, Russia, Japan, South Korea and North Korea?

Delury: The six-party talks has not been active for nearly a decade. I wonder if the platform has outlived its purpose. There was something unwieldy about the talks that hindered progress, as each country insisted on its own narrow interests at the expense of the ultimate goal of denuclearization.

We could keep the format alive to have a final resolution on agreements that are hammered out bilaterally, or in smaller multilateral settings. This is because the real heavy lifting of diplomacy that needs to happen is easier in bilateral and smaller settings.

KH: The decision to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system is controversial, with Beijing sternly opposed to it. Can you explain?

Delury: The THAAD is a piece of a tactical network to be based in South Korea to defend against North Korea’s provocations, and Seoul has all the reasons to deploy the system.

The issue has become a serious irritant on Seoul-Beijing relations. It has affected not just security but economic ties. The Chinese are upset, as they view it as a way for the US to lure South Korea into a regional system of missile defense, intelligence sharing and containment of China.

They perceive it in terms of US-China relations, not simply South Korea-China relations. They also think it has more than a tactical significance, a strategic one. There was some hope in using THAAD to pressure Beijing to do more about Pyongyang, but given recent developments like China’s alleged blockade of trade with South Korean companies, it has lost its utility on that front.

KH: Do you see any possibility of North Korea becoming a “developmental dictatorship” under Kim Jong-un, as China has done since 1978 economic reform and opening?

Delury: The best shot we have is that Kim Jong-un is a “Deng Xiaoping-wannabe.” Kim is young and will probably evolve. He has put equal emphasis on economic development as nuclear statehood through the “Byungjin Line” policy.

A prosperous North Korea that is economically integrated with the South and Northeast Asia is the kind that could give up its nuclear weapons. That is our best bet, and we should do more to encourage that side of Kim Jong-un.

By Joel Lee (joel@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)