Coinciding with the 65th anniversary of the start of the Korean War (1950-53), a British journalist has published a Korean-language edition of his book vividly depicting the sacrifices made by British and Australian soldiers.

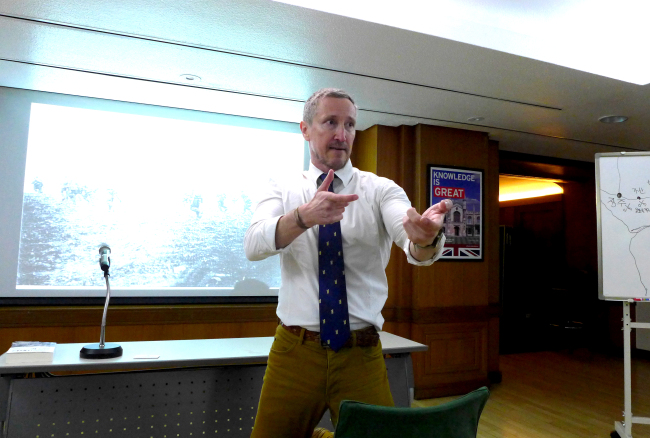

“Scorched Earth, Black Snow: The First Year of the Korean War,” originally printed in 2011 in English, was authored by Andrew Salmon, a longtime Korean resident and journalist.

At a press conference at the British Embassy in Seoul on June 19, British Ambassador Charles Hay said his country’s participation in the war marked a defining moment in the 132-year relationship between the U.K. and Korea.

“Scorched Earth, Black Snow: The First Year of the Korean War,” originally printed in 2011 in English, was authored by Andrew Salmon, a longtime Korean resident and journalist.

At a press conference at the British Embassy in Seoul on June 19, British Ambassador Charles Hay said his country’s participation in the war marked a defining moment in the 132-year relationship between the U.K. and Korea.

“We are immensely proud to have contributed to the war, which is largely forgotten now,” said Hay, who served five years in the British infantry as a captain. “Andrew Salmon has brought the war alive to the public by drawing extensively on personal reminiscences.”

The embassy’s defense attache Brig. Andrew Cliff said the book captured the essence of the war by vividly describing battle scenes.

“Warfare, for all its technologies and strategies, is ultimately the battle of peoples’ wills,” he said.

The 735-page book recounts the story of the British Commonwealth’s 27th Infantry Brigade, comprised of the Middlesex Regiment and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, alongside the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, in the war’s early stages from August to the end of 1950.

These units were the first U.N. forces to land in Korea after the Americans, spearheading the allied advance north and retreat south as rearguards ― the most dangerous combat task. The book also narrates the role of Royal Marine “green beret” commandos.

Many of the soldiers had fought in World War II, and were “fit, well-trained and used to the Asian terrain,” Salmon pointed out, based on his two years of interviews with 93 British, Australian, American and Korean veterans.

“I wanted to capture these stories before they were lost forever,” the author highlighted.

During an interview, a former commando hit a cup of coffee, which flew across the carpet, Salmon said. “He just ignored it and kept talking. After the interview, his wife came to me and said, ‘I won’t sleep tonight.’”

“When I asked her why,” he added, “She responded, ‘When my husband remembers the war, he throws punches and kicks in his sleep.’”

The Korean War was a brutal conflict with significant collateral damage, the writer stressed. Often, U.N. and North Korean forces did not take prisoners, killing them instead.

On Sept. 17, in the Nakdong River battle to capture the town of Seongju, the U.S. Air Force mistakenly dropped napalm on British soldiers, who were fighting North Koreans in close combat. The “friendly fire” killed 60 Argylls.

The Argyll’s 38-year-old Maj. Kenny Muir quickly gathered 12 soldiers to set a skirmish line and evacuate the wounded. He was killed in action and awarded the Victoria Cross ― the highest military decoration for valor across the Commonwealth.

Then, in a bizarre incident in Sariwon, south of Pyongyang, 120 Argylls and 2,000 North Korean soldiers marched past each other on a narrow road, not realizing they were enemies. The North Koreans shook hands with the Argylls, shouting, “Russki! Russki!” ― mistaking them for Russians.

A firefight soon broke out, with Argylls machine-gunning the disordered North Koreans. Two British veterans whom Salmon interviewed still possessed North Korean epaulets handed to them by the enemies during the march. “We felt almost sad to shoot down these friendly North Koreans,” one veteran told the author.

After U.N. forces advanced north to the very edge of the Korean peninsula, they were confronted by a “human wave” of 260,000 Chinese soldiers, who, one veteran recalled, “poured down a hillside like a waterfall.”

The U.N. forces lost North Korea in less than a month, and retreated south in deadly cold, joined by 700,000 Koreans who had lost their homes or did not wish to live under communism.

Salmon said that the “biggest losers” of the war were North and South Korea, which remain bitter enemies. “However, while South Korea could not win the war, it won the peace,” the author underscored. “The political, economic and social miracles that have taken place here erased memories of the dark days of 1950, described in the book.”

In a related event Friday, the British and Irish embassies unveiled a memorial plaque near Goyang city, northeast of Seoul, to commemorate the “Battle of Happy Valley,” which took place Jan. 3-4, 1951.

In that battle, the Royal Ulster Rifles, the VIII Kings Royal Irish Hussars and the Royal Artillery lost 157 men holding back communist troops during the evacuation of Seoul.

By Joel Lee (joel@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)