‘A room of her own’

Feminist art pioneer Yun Suk-nam talks about life, her mother and great women in history

By Lee Woo-youngPublished : May 29, 2015 - 18:58

The high-ceilinged studio of artist Yun Suk-nam is filled with images of women.

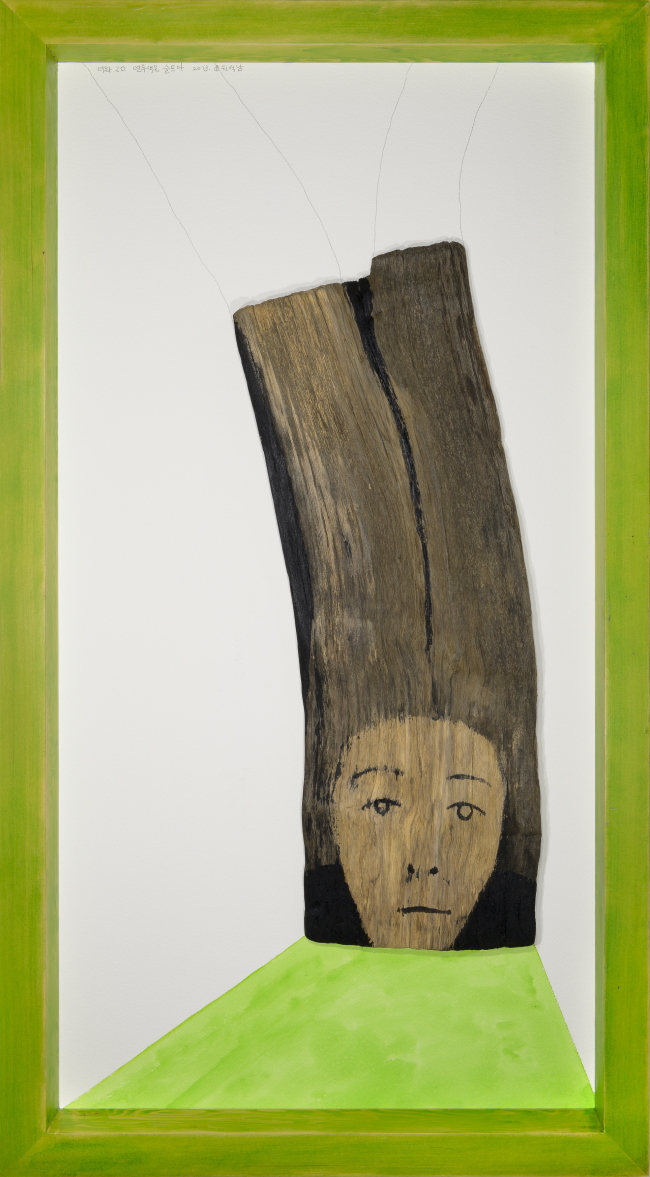

Her signature paintings of women painted on wood blocks occupy one side of her spacious studio in a scenic, rural village in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi Province.

“I’m making new pieces for a very nice exhibit at Baengnyeonsa Temple in Haenam,” the 76-year-old artist said enthusiastically.

“I’m going to surround the walls of the temple with these wood paintings.”

Her signature paintings of women painted on wood blocks occupy one side of her spacious studio in a scenic, rural village in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi Province.

“I’m making new pieces for a very nice exhibit at Baengnyeonsa Temple in Haenam,” the 76-year-old artist said enthusiastically.

“I’m going to surround the walls of the temple with these wood paintings.”

Yun is a pioneer of feminist art in Korea. Women have been the central theme of her work during her 36-year career.

A retrospective of Yun’s work is being held at the Seoul Museum of Art.

The exhibition tells the diverse stories of the women Yun selected to represent in paintings, drawings, wood sculptures and installations.

But her work does not conform to the stereotypical image of feminist art.

While feminist art is largely represented in the form of symbolic or radical sexual images that attempt to address sexism, Yun’s works touch on a more universal language ― motherhood.

It features the life of her mother, the lives of women in history and Yun’s interest in nature and community.

“I didn’t even know what ‘feminism’ meant before. All I did was to talk about my mother,” Yun said.

Yun’s unique exploration of Korean women based on the life of her mother brought together feminist activists in the 1980s, who started to label her work as “feminist art.”

“That’s when I began to think about the link between my art and the society I live in,” she said.

Yun and other female artists and feminist activists formed groups, studied feminism academically and held discussions on women’s issues, during which Yun found her theoretical underpinnings.

Her work has received high praise inside and outside Korea. She participated in the Venice Biennale in 1995 with her installation “Mother’s Story” and became the first female artist to win the prestigious Lee Jung-seop Art Award in 1996.

Yun founded the feminist magazine “If” in 1997 and served as the first managing editor of the magazine. She was one of the founders of the Seoul International Women’s Film Festival.

However, the start of her artistic career had nothing to do with the feminist movement.

It began as a quest to find her own identity as a woman.

She calls her life before she started painting “lost.” Art was a door to her true self, after living more than a decade as a housewife.

Yun said she had a “thirst” to find proof for her existence. Her life was no different from that of other women her age. She got married when she was 28 and lived with her mother-in-law, making three meals a day for her family. From the outside, her middle-class life was enviable.

“But I wanted my life back,” she said.

Yun remembered precisely the day she started painting and how she felt on that day.

“It was April 25, 1979. I was 40,” said Yun. “I felt exhilarated. I instantly knew it was the right path for me.”

It was a dream come true for her. She could finally find answers to the lifelong questions she had since she was a child ― why does she exist and what does she live for? She created “a room of her own” at her house, used solely for painting and thinking.

The first subject she began to paint was her mother, inviting her to her house twice a week to pose for her.

“I decided to draw my mother who I respect and love the most in the world. I thought if I didn’t draw her, who would?

Many of the images in her work represent her mother. Sometimes, her mother is represented as a 19-year-old girl, or an exhausted worker or an elegant lady in a delicate hanbok (traditional Korean dress), or a fragile old woman huddled up like a baby.

“My mother became a widow when she was 39. After my father passed away, she was left with six young children on the street. She basically built a new life from scratch. She did all kinds of work, from making mud bricks to building a new house for us and selling goods at the market,” said Yun.

This may have been a typical life for a Korean mother just after the Korean War. Yun said she felt the deepest respect toward the mothers who survived that turbulent time.

Yun held her first solo exhibition in 1982, with paintings that depicted women modeled after her mother. The exhibition caught the eyes of two female artists and activists who suggested she hold another exhibition with them.

Their second exhibition, “From Half to One” in 1986, was considered the start of feminist art in Korea.

“Art back then was either abstract paintings or landscape paintings. … I found them empty and thought, ‘What did they have to do with my life?’” Yun said in an interview with art researcher Kim Kang for the publication of the Korean Contemporary Art Book.

In the 1990s, she made another transition ― a shift in her painting style.

She wanted to move outside the two-dimensional constraints of canvas and started painting on wood blocks after seeing a huge wood installation at Bronx Museum in New York in 1990. She painted images of women, including her mother, on wood pieces and assembled them to look like wooden sculptures.

During the interview, she confessed her own conflicts of using “feminine” materials for her “feminist art.”

“I was really conflicted inside regarding the types of materials I would use under the categorization of feminist art. Somehow I clung to the idea that materials for feminist art should be feminine and soft. But Bourgeois’ works completely changed the stereotypical ideas I had,” she said.

Another encounter with the works of French artist Louise Bourgeois in New York brought a huge change in her work as well. She was shocked that Bourgeois used pipes and metal and steel to express the strong physique of the spider installation “Maman.”

Yun also expanded her subject from her own mother and anonymous women to great women in Korean history and the community. She uncovered stories of great women in history whose great deeds made lasting influences on future generations. Such women include painter and poet Heo Nanseolheon of the Joseon period, poet and “gisaeng” (Korea’s to equivalent to Japan’s geisha) Lee Mae-chang, who saved hundreds of lives by offering all her wealth for food during a severe famine on Jejudo Island, artist Na Hye-seok and dancer Choi Seung-hee.

In the retrospective, she presented a new heart-shaped pink installation that represented the warm-hearted Lee Mae-chang, who fed the people of Jejudo Island by spending all her wealth during a severe famine in the Joseon period.

Another new installation is about the talented Joseon-era poet and painter Heo Nanseolheon, who died at the age of 27.

“My plan is to uncover more stories of women we have been forgotten in our history and tell their stories,” Yun said.

Yun’s 1997 work “The Seeding of Lights,” consisting of 999 wood pieces of women, is on display at the Seoul exhibition.

Asked why one piece is missing, she answered: “1,000 is the complete number which I think represents an equal world for men and women. But we haven’t reached it yet. One piece is just a small gap you can skip, but I wonder how long it would take to fill it,” she said.

By Lee Woo-young (wylee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)