Korea’s rape laws self-contradict

System fails to protect male victims in military, among others

By Korea HeraldPublished : April 27, 2015 - 20:29

Earlier this month, a 21-year-old marine was sentenced to one year and six months in prison for sexually abusing at least four of his male subordinates over the course of 20 occasions in 2013, including forcing them to perform oral sex on him.

However, when prosecutors in Gwangju indicted him on sexual abuse charges, they could not apply the nation’s rape laws ― as the law only acknowledges rape when the “female sex organ has been penetrated by the male sex organ.”

This means same-sex rape cannot be legally acknowledged in Korea. The laws also don’t recognize any other forms of sexual penetration ― such as forced anal or oral sex, or inserting of a foreign object into the body ― as rape, regardless of the gender of the victim.

Scholars and legal experts say the current law fails to protect victims of sexual violence with its limited definition of rape, especially those in the military who are vulnerable to power abuse.

“The current law says that penetration of the vagina by the male sex organ is the most serious form of sexual abuse,” said Chang Da-hye, a legal scholar at the Korean Institute of Criminology.

“But when you think about it, the physical and emotional damage to a victim who experienced penetration of other body parts can be in fact more serious than those who have been ‘raped’ as defined by the current law.”

‘Rape’ and ‘like-rape’

In many countries, including the U.S. and France, rape is defined as any act of sexual penetration, whatever its nature, committed against another person.

The International Criminal Court defines it as any “penetration, however slight, of any part of the body of the victim or of the perpetrator with a sexual organ, or the anal or genital opening of the victim with any object or any other part of the body.”

The World Health Organization defines it as “physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration ― even if slight ― of the vulva or anus, using body parts or an object.”

Yet in Korea, the definition of rape is specifically limited to penetration of the female genitals by the male sex organ, and other forms of forced sexual penetration are defined as “like-rape” ― which carry lighter penalties than what the law defines as “rape.”

Currently, the Korean law stipulates that the punishment for “rape” is imprisonment for a definite term of at least three years, which is the heaviest among all forms of criminalized sexual activities against able-bodied adults.

Those who commit what the law defines as “like rape” as of 2013 ― “inserting one’s genitals into the inner part of another person’s body such as mouth or anus except genitals, or inserting a part of his or her body other than genitals, such as a finger, or any foreign objects into another person’s body” ― are punishable by at least two years in prison.

Those who “rape” a person with disabilities are punishable by at least seven years behind bars, while those who commit “like rape” against a person with disabilities only face at least five years imprisonment.

“The law should either expand its definition of rape ― by combining the current definitions of ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape’ ― or enforce heavier penalties on those who commit ‘like-rape,’ to an equivalent level of the ones on ‘rape,’” said Chun Jung-ah, an attorney who has represented many victims of sexual violence.

“Ultimately, it’s the judge who makes the final decision for every case. But if the law stipulates that the penalties for ‘rape’ are heavier than the ones for ‘like-rape,’ it’s certainly more likely that those with ‘like-rape’ charges will face lighter punishment.”

Patriarchy factor

Until 1995, Korea’s rape laws were under the chapter of “chastity crimes” of the criminal code. It was only in 2013 that the definition of “like-rape” was introduced and criminalized. Also until the same year, it did not acknowledge rape by women and therefore it was impossible for male victims to file complaints with the police.

“Until 1995, the primary purpose of rape laws was to protect married women’s chastity (and virginity), to minimize their chance of bearing illegitimate children. It’s linked to the patriarchal notion that values pure bloodlines above all else,” said scholar Chang at the Korean Institute of Criminology.

“Traditionally, when a woman was raped, it was considered as a damage to her husband or her father, and the reputation of her household, not herself. Such notions made it impossible for lawmakers to think of women as potential rapists in the past. It also made it difficult for them to think that rape can also occur between same-sex individuals.”

The law now stipulates that it is to protect an individual’s sexual autonomy, regardless of his or her gender. However, Kim Jong-hye, a visiting researcher at the GongGam Human Rights Law Foundation, said the current rape laws contradict with what it’s supposed to protect, by separating “rape” and “like-rape.”

“If its primary purpose is to protect women’s chastity and the so-called ‘pure bloodlines’ of households, the current law makes sense, because a forced penetration of female sex organ by the male sex organ is the only form of abuse that can lead to an unwanted pregnancy,” Kim said.

“But if the purpose is to protect one’s sexual autonomy, as it is stated in the law, then how is a penetration of genitals any worse than any other forms of penetration? They are all a serious invasion of one’s sexual autonomy and violation of human rights.”

Kim argued that the current law promotes a notion that for women, losing their virginity or chastity is the most serious form of damage, and something that a woman victim should be ashamed of.

“It’s like a vicious cycle,” she said. “The laws reflect today’s society, where many female victims of sexual violence are still blamed for being too drunk or being too sexually provocative. And by enforcing heavier penalties for ‘rape’ than ‘like-rape,’ the laws spread the idea that the most serious or cruel form of sexual abuse is done by the male sex organ only.”

Military power abuse

Experts say the most vulnerable under the current law are in fact male victims of military sexual violence by their male superiors.

“Most of sexual violence cases against women involve both ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape.’ It’s rare for rapists to commit ‘like-rape’ only (against women),’” said Bae Bok-ju, an activist supporting women with disabilities who have been sexually abused.

“So if convicted, the perpetrator who abused women can be punished for both ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape.’ But male perpetrators who abused men will only be punished on the grounds of ‘like-rape,’ which carry lighter penalties, under the current law.”

Korea’s military criminal law also differentiates “rape” and “like-rape,” and stipulates heavier penalties for rape charges -― imprisonment of at least five years ― than for ‘like-rape,’ which is punishable by at least three years in prison. According to the law, all sexual abuse between same-sex soldiers can only be charged with “like-rape.”

Last year, a male Army conscript surnamed Yoon died after six male colleagues allegedly hit him in the chest while he was eating, which led him to choke on his food. According to the Military Human Rights Center, Yoon had been constantly sexually assaulted by the bullies, on top of being physically and verbally abused on a daily basis. Also last year, a 26-year-old army sergeant was arrested on charges of sexually abusing his subordinate at least three times in his residence.

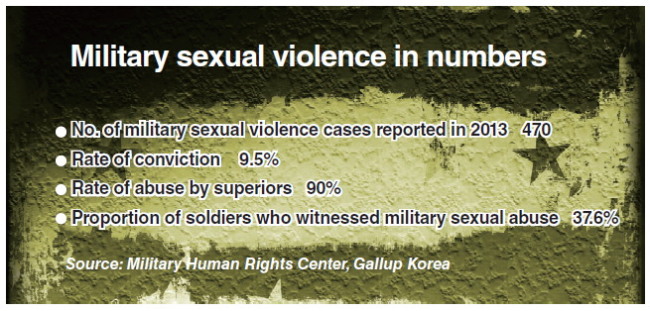

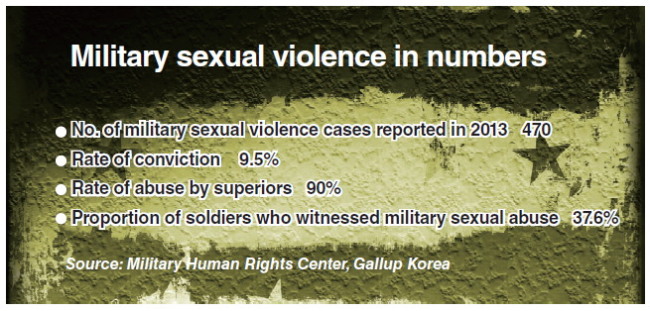

According to a 2013 study by Gallup Korea, an independent research firm, 37.6 percent of Korean men in their 20s and 30s said they have either witnessed or heard about sexual abuse cases while serving their military duties, while 31.2 percent said they think the issue of military sexual violence as a form of power abuse is serious.

Ninety percent of perpetuators of military sex abuse cases among male individuals were the victims’ superiors, according to a 2013 scholarly thesis by Lim Tae-hun, who heads the Military Human Rights Center.

Some 470 military sexual abuse cases were reported in 2013, but only 39.5 percent ended with a conviction, according to data released by Lim’s organization. Many cases remain unreported.

Education needed

Lawyer Chun has witnessed many male victims of sexual violence by men end up dropping charges. She said all male and female victims of sexual violence can experience severe post-traumatic stress regardless of the perpetrator’s gender.

“Many male victims I’ve seen, however, suffer from an extreme sense of humiliation, which I think is different from the (reaction) of female victims,” she said.

“One of the victims in fact told me, ‘I thought only women become victims of sexual abuse. I feel so humiliated that this actually has happened to me, and I don’t know who to share this with. I can’t even tell my close friends.’ A lot of them withdraw a complaint because they feel humiliated about talking to the police ― or in court ― about their experience. They have a hard time accepting themselves as victims.”

Shin Jin-hee, a court-appointed attorney, said the system at the Court for Armed Forces should change as much as the current rape laws. One of the biggest existing problems, she said, is that the court very often does not inform soldier victims of military abuse that they have the right to speak to a lawyer, and are entitled to a court-appointed attorney if they can’t afford to hire one.

“The law should be revised, that is for sure,” she said. “But I think what is desperately needed in military as well as the civil Korean society is human rights education, and that you can’t use sexual harassment or abuse as a ‘means of discipline’ or anything else.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

However, when prosecutors in Gwangju indicted him on sexual abuse charges, they could not apply the nation’s rape laws ― as the law only acknowledges rape when the “female sex organ has been penetrated by the male sex organ.”

This means same-sex rape cannot be legally acknowledged in Korea. The laws also don’t recognize any other forms of sexual penetration ― such as forced anal or oral sex, or inserting of a foreign object into the body ― as rape, regardless of the gender of the victim.

Scholars and legal experts say the current law fails to protect victims of sexual violence with its limited definition of rape, especially those in the military who are vulnerable to power abuse.

“The current law says that penetration of the vagina by the male sex organ is the most serious form of sexual abuse,” said Chang Da-hye, a legal scholar at the Korean Institute of Criminology.

“But when you think about it, the physical and emotional damage to a victim who experienced penetration of other body parts can be in fact more serious than those who have been ‘raped’ as defined by the current law.”

‘Rape’ and ‘like-rape’

In many countries, including the U.S. and France, rape is defined as any act of sexual penetration, whatever its nature, committed against another person.

The International Criminal Court defines it as any “penetration, however slight, of any part of the body of the victim or of the perpetrator with a sexual organ, or the anal or genital opening of the victim with any object or any other part of the body.”

The World Health Organization defines it as “physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration ― even if slight ― of the vulva or anus, using body parts or an object.”

Yet in Korea, the definition of rape is specifically limited to penetration of the female genitals by the male sex organ, and other forms of forced sexual penetration are defined as “like-rape” ― which carry lighter penalties than what the law defines as “rape.”

Currently, the Korean law stipulates that the punishment for “rape” is imprisonment for a definite term of at least three years, which is the heaviest among all forms of criminalized sexual activities against able-bodied adults.

Those who commit what the law defines as “like rape” as of 2013 ― “inserting one’s genitals into the inner part of another person’s body such as mouth or anus except genitals, or inserting a part of his or her body other than genitals, such as a finger, or any foreign objects into another person’s body” ― are punishable by at least two years in prison.

Those who “rape” a person with disabilities are punishable by at least seven years behind bars, while those who commit “like rape” against a person with disabilities only face at least five years imprisonment.

“The law should either expand its definition of rape ― by combining the current definitions of ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape’ ― or enforce heavier penalties on those who commit ‘like-rape,’ to an equivalent level of the ones on ‘rape,’” said Chun Jung-ah, an attorney who has represented many victims of sexual violence.

“Ultimately, it’s the judge who makes the final decision for every case. But if the law stipulates that the penalties for ‘rape’ are heavier than the ones for ‘like-rape,’ it’s certainly more likely that those with ‘like-rape’ charges will face lighter punishment.”

Patriarchy factor

Until 1995, Korea’s rape laws were under the chapter of “chastity crimes” of the criminal code. It was only in 2013 that the definition of “like-rape” was introduced and criminalized. Also until the same year, it did not acknowledge rape by women and therefore it was impossible for male victims to file complaints with the police.

“Until 1995, the primary purpose of rape laws was to protect married women’s chastity (and virginity), to minimize their chance of bearing illegitimate children. It’s linked to the patriarchal notion that values pure bloodlines above all else,” said scholar Chang at the Korean Institute of Criminology.

“Traditionally, when a woman was raped, it was considered as a damage to her husband or her father, and the reputation of her household, not herself. Such notions made it impossible for lawmakers to think of women as potential rapists in the past. It also made it difficult for them to think that rape can also occur between same-sex individuals.”

The law now stipulates that it is to protect an individual’s sexual autonomy, regardless of his or her gender. However, Kim Jong-hye, a visiting researcher at the GongGam Human Rights Law Foundation, said the current rape laws contradict with what it’s supposed to protect, by separating “rape” and “like-rape.”

“If its primary purpose is to protect women’s chastity and the so-called ‘pure bloodlines’ of households, the current law makes sense, because a forced penetration of female sex organ by the male sex organ is the only form of abuse that can lead to an unwanted pregnancy,” Kim said.

“But if the purpose is to protect one’s sexual autonomy, as it is stated in the law, then how is a penetration of genitals any worse than any other forms of penetration? They are all a serious invasion of one’s sexual autonomy and violation of human rights.”

Kim argued that the current law promotes a notion that for women, losing their virginity or chastity is the most serious form of damage, and something that a woman victim should be ashamed of.

“It’s like a vicious cycle,” she said. “The laws reflect today’s society, where many female victims of sexual violence are still blamed for being too drunk or being too sexually provocative. And by enforcing heavier penalties for ‘rape’ than ‘like-rape,’ the laws spread the idea that the most serious or cruel form of sexual abuse is done by the male sex organ only.”

Military power abuse

Experts say the most vulnerable under the current law are in fact male victims of military sexual violence by their male superiors.

“Most of sexual violence cases against women involve both ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape.’ It’s rare for rapists to commit ‘like-rape’ only (against women),’” said Bae Bok-ju, an activist supporting women with disabilities who have been sexually abused.

“So if convicted, the perpetrator who abused women can be punished for both ‘rape’ and ‘like-rape.’ But male perpetrators who abused men will only be punished on the grounds of ‘like-rape,’ which carry lighter penalties, under the current law.”

Korea’s military criminal law also differentiates “rape” and “like-rape,” and stipulates heavier penalties for rape charges -― imprisonment of at least five years ― than for ‘like-rape,’ which is punishable by at least three years in prison. According to the law, all sexual abuse between same-sex soldiers can only be charged with “like-rape.”

Last year, a male Army conscript surnamed Yoon died after six male colleagues allegedly hit him in the chest while he was eating, which led him to choke on his food. According to the Military Human Rights Center, Yoon had been constantly sexually assaulted by the bullies, on top of being physically and verbally abused on a daily basis. Also last year, a 26-year-old army sergeant was arrested on charges of sexually abusing his subordinate at least three times in his residence.

According to a 2013 study by Gallup Korea, an independent research firm, 37.6 percent of Korean men in their 20s and 30s said they have either witnessed or heard about sexual abuse cases while serving their military duties, while 31.2 percent said they think the issue of military sexual violence as a form of power abuse is serious.

Ninety percent of perpetuators of military sex abuse cases among male individuals were the victims’ superiors, according to a 2013 scholarly thesis by Lim Tae-hun, who heads the Military Human Rights Center.

Some 470 military sexual abuse cases were reported in 2013, but only 39.5 percent ended with a conviction, according to data released by Lim’s organization. Many cases remain unreported.

Education needed

Lawyer Chun has witnessed many male victims of sexual violence by men end up dropping charges. She said all male and female victims of sexual violence can experience severe post-traumatic stress regardless of the perpetrator’s gender.

“Many male victims I’ve seen, however, suffer from an extreme sense of humiliation, which I think is different from the (reaction) of female victims,” she said.

“One of the victims in fact told me, ‘I thought only women become victims of sexual abuse. I feel so humiliated that this actually has happened to me, and I don’t know who to share this with. I can’t even tell my close friends.’ A lot of them withdraw a complaint because they feel humiliated about talking to the police ― or in court ― about their experience. They have a hard time accepting themselves as victims.”

Shin Jin-hee, a court-appointed attorney, said the system at the Court for Armed Forces should change as much as the current rape laws. One of the biggest existing problems, she said, is that the court very often does not inform soldier victims of military abuse that they have the right to speak to a lawyer, and are entitled to a court-appointed attorney if they can’t afford to hire one.

“The law should be revised, that is for sure,” she said. “But I think what is desperately needed in military as well as the civil Korean society is human rights education, and that you can’t use sexual harassment or abuse as a ‘means of discipline’ or anything else.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[KH Explains] No more 'Michael' at Kakao Games](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050183_0.jpg&u=20240428180321)

![[Herald Interview] Mistakes turn into blessings in street performance, director says](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050150_0.jpg&u=20240428174656)