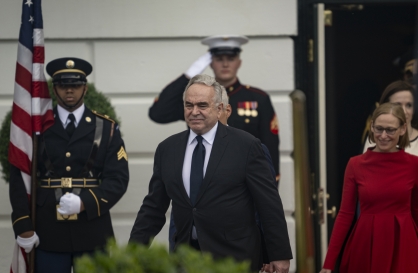

[Kim Myong-sik] Listening to arguments against pension reform

By Korea HeraldPublished : Nov. 26, 2014 - 20:47

The issue of how to reform the public pension system has become a central talking point. The ruling Saenuri Party has drafted a revised version of the Government Employees Pension Law under the guideline of “pay more, receive less.” The 1 million members of the nation’s bureaucratic community including retirees are vehemently against the reform move while the rest of the people look on warily, many reluctant to sympathize.

I subscribe to the National Pension Service system, which deposits a six-digit sum into my bank account every month. That monthly allowance is about a quarter to a third the average amount of the public servants’ pension. The seemingly large difference between the universal National (Gukmin) Pension and Government Employees (Gongmuwon) Pension is the focus of the current pension controversy.

pension. The seemingly large difference between the universal National (Gukmin) Pension and Government Employees (Gongmuwon) Pension is the focus of the current pension controversy.

When I retired from my newspaper job years ago, I received a lump sum severance pay as most corporate employees do. During my “second career,” working for the government, a notice came from the NPS telling me that I would be receiving my “pension” in one month, when I turned 60. How nice! My wife was happy too, saying that the amount was large enough to cover the monthly “management fee” for my apartment.

Thus, I became a pensioner, one of about 3 million people who are taking back the money they and their employers had deposited while working plus a little the government chipped in out of its welfare budget. According to a bit of research I did on the Internet, an average NPS subscriber collects 330,000 won a month and those who paid their dues to the NPS for over 20 years get nearly 900,000 won monthly.

Retired military officers, public servants and school teachers are paid much more ― from 2 million won to 4 million won. In order to support this “privileged class,” numbering about half a million, over 2 trillion won has to be set aside from the national budget. As debates are heating up between the advocates of pension reform and the present and future beneficiaries over the monetary gap, I spent some time listening to what the two sides have to say, assuming a position of neutrality.

There are numerous Internet postings from ex-bureaucrats, retired officials and active members of government offices, rejecting first of all the allegations that a “blood tax” is being poured to make up for the deficits in the pension fund. As the employer in the pension contract, established through a special law half a century ago, the government should fulfill its part of the obligation from its revenues, the antireformers argue. The “blood tax” concept is irrelevant, they claim.

Then there is the complaint that the Government Employees Pension Service has been poorly managed over the past decades, with trillions of won “squandered” during the IMF bailout period of 1997-98, which “permanently” crippled the public pension system. Some 5.9 trillion won ― worth about 15 trillion won now ― went to the relief of ailing financial institutions and the huge funds have simply “evaporated,” according to the opponents.

Operational inefficiency resulted from the appointment of unprofessional figures as GEPS executives, many from political circles, they argue quite plausibly. Whenever the stock market was bearish, the public servants pension fund intervened only to suffer huge losses. The pension fund recorded the worst profit rate among institutional investors, they claim.

When the pension systems for public servants, namely government officials, military officers and school teachers, began in the early 1960s under the then-military government, people in these professions were paid slightly more than half the amount that those in the private sector received. “We had no money to send our children to hagwon or buy clothes for them. We endured this with pride, expecting stability from the pension,” said a housewife who married a public official in 1977 and now lives on 3.6 million won a month from the pension fund.

Their arguments went further: The Blue House and the Saenuri Party are deliberately pitting national pension subscribers against public servant pensioners with the conservative media agitating the former by emphasizing the difference in benefits; the Korea Pension Association, an academic research body offering advice to the authorities, actually represents the interests of financial organizations; and the move to collect 3-4 percent contributions (a forced deduction) from present beneficiaries is unconstitutional.

Reading line after line of the opponents’ claims, this supposedly neutral observer found it hard to criticize their self-interest. Yet I was not quite convinced by one of the assertions: “While those in the private sector worked for their personal and corporate interests, we devoted our lives to the national well-being. Aren’t we entitled to ask for better recognition and treatment?” In the roaring ’70s and ’80s, everyone worked hard for the sake of the nation.

Placards hoisted by the Korea Government Employees Union say, “The Nation Has No Future When Public Pension Systems Are Altered!” Yes, we all should think of the future of the Republic of Korea and deeper consideration is needed before we make up our minds on this complex issue. Coincidentally, Statistics Korea last week produced significant figures on the demographic changes of the republic in forthcoming decades.

It was a renewed warning of a population catastrophe. (No conspiracy theories, please!) Korea’s productive population ― those between the ages of 15 and 64 ― will begin to decline in 2016; the nation will become an aged society in 2017 with people 65 or older accounting for 14 percent; and then we will become a super-aged society with 1 in 5 in that category by 2026. Ten years from now, three working people will have support at least one old person in addition to their own families.

We should realize that the pension problem in Korea resulted partly from poor management of the fund, but chiefly from the failure to foresee that so few people will have to support so many old people in just a few decades. In order to prevent a default by the public servants pension fund as well as the universal NPS system, all interest groups need to forego selfishness and explore possible solutions.

A catastrophe should be delayed until our young men and women choose to get married early and bear two or more children as their parents did.

By Kim Myong-sik

Kim Myong-sik is a former editorial writer for The Korea Herald. ― Ed.

I subscribe to the National Pension Service system, which deposits a six-digit sum into my bank account every month. That monthly allowance is about a quarter to a third the average amount of the public servants’

pension. The seemingly large difference between the universal National (Gukmin) Pension and Government Employees (Gongmuwon) Pension is the focus of the current pension controversy.

pension. The seemingly large difference between the universal National (Gukmin) Pension and Government Employees (Gongmuwon) Pension is the focus of the current pension controversy. When I retired from my newspaper job years ago, I received a lump sum severance pay as most corporate employees do. During my “second career,” working for the government, a notice came from the NPS telling me that I would be receiving my “pension” in one month, when I turned 60. How nice! My wife was happy too, saying that the amount was large enough to cover the monthly “management fee” for my apartment.

Thus, I became a pensioner, one of about 3 million people who are taking back the money they and their employers had deposited while working plus a little the government chipped in out of its welfare budget. According to a bit of research I did on the Internet, an average NPS subscriber collects 330,000 won a month and those who paid their dues to the NPS for over 20 years get nearly 900,000 won monthly.

Retired military officers, public servants and school teachers are paid much more ― from 2 million won to 4 million won. In order to support this “privileged class,” numbering about half a million, over 2 trillion won has to be set aside from the national budget. As debates are heating up between the advocates of pension reform and the present and future beneficiaries over the monetary gap, I spent some time listening to what the two sides have to say, assuming a position of neutrality.

There are numerous Internet postings from ex-bureaucrats, retired officials and active members of government offices, rejecting first of all the allegations that a “blood tax” is being poured to make up for the deficits in the pension fund. As the employer in the pension contract, established through a special law half a century ago, the government should fulfill its part of the obligation from its revenues, the antireformers argue. The “blood tax” concept is irrelevant, they claim.

Then there is the complaint that the Government Employees Pension Service has been poorly managed over the past decades, with trillions of won “squandered” during the IMF bailout period of 1997-98, which “permanently” crippled the public pension system. Some 5.9 trillion won ― worth about 15 trillion won now ― went to the relief of ailing financial institutions and the huge funds have simply “evaporated,” according to the opponents.

Operational inefficiency resulted from the appointment of unprofessional figures as GEPS executives, many from political circles, they argue quite plausibly. Whenever the stock market was bearish, the public servants pension fund intervened only to suffer huge losses. The pension fund recorded the worst profit rate among institutional investors, they claim.

When the pension systems for public servants, namely government officials, military officers and school teachers, began in the early 1960s under the then-military government, people in these professions were paid slightly more than half the amount that those in the private sector received. “We had no money to send our children to hagwon or buy clothes for them. We endured this with pride, expecting stability from the pension,” said a housewife who married a public official in 1977 and now lives on 3.6 million won a month from the pension fund.

Their arguments went further: The Blue House and the Saenuri Party are deliberately pitting national pension subscribers against public servant pensioners with the conservative media agitating the former by emphasizing the difference in benefits; the Korea Pension Association, an academic research body offering advice to the authorities, actually represents the interests of financial organizations; and the move to collect 3-4 percent contributions (a forced deduction) from present beneficiaries is unconstitutional.

Reading line after line of the opponents’ claims, this supposedly neutral observer found it hard to criticize their self-interest. Yet I was not quite convinced by one of the assertions: “While those in the private sector worked for their personal and corporate interests, we devoted our lives to the national well-being. Aren’t we entitled to ask for better recognition and treatment?” In the roaring ’70s and ’80s, everyone worked hard for the sake of the nation.

Placards hoisted by the Korea Government Employees Union say, “The Nation Has No Future When Public Pension Systems Are Altered!” Yes, we all should think of the future of the Republic of Korea and deeper consideration is needed before we make up our minds on this complex issue. Coincidentally, Statistics Korea last week produced significant figures on the demographic changes of the republic in forthcoming decades.

It was a renewed warning of a population catastrophe. (No conspiracy theories, please!) Korea’s productive population ― those between the ages of 15 and 64 ― will begin to decline in 2016; the nation will become an aged society in 2017 with people 65 or older accounting for 14 percent; and then we will become a super-aged society with 1 in 5 in that category by 2026. Ten years from now, three working people will have support at least one old person in addition to their own families.

We should realize that the pension problem in Korea resulted partly from poor management of the fund, but chiefly from the failure to foresee that so few people will have to support so many old people in just a few decades. In order to prevent a default by the public servants pension fund as well as the universal NPS system, all interest groups need to forego selfishness and explore possible solutions.

A catastrophe should be delayed until our young men and women choose to get married early and bear two or more children as their parents did.

By Kim Myong-sik

Kim Myong-sik is a former editorial writer for The Korea Herald. ― Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)