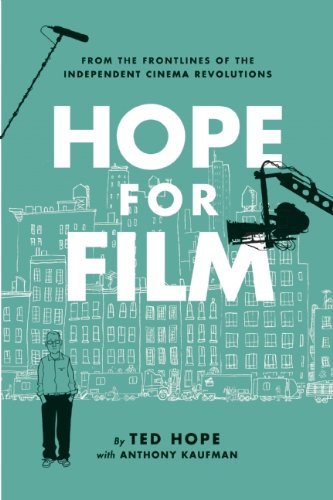

By Ted Hope with Anthony Kaufman

(Soft Skull)

Ted Hope’s new book “Hope for Film” is part memoir, part manual, part manifesto as it traces his long career in independent filmmaking, mostly and most notably as a producer but more recently with a brief excursion into the nonprofit world and then onto the evolving interface of technology, creation and distribution.

Eagle-eyed readers will spot the plurals in the subtitle, “From the Frontlines of the Independent Cinema Revolutions” ― indication that the book is not about a fixed form but rather a fluid environment.

Hope is, for those who read film credits like tea leaves, a long-standing mark of quality, someone who has seen through American independent filmmaking from the scrappy days of the early 1990s on to a series of rise and fall cycles. His first notable credit as producer was on Hal Hartley’s 1989 “The Unbelievable Truth,” and he remained for most of his producing career an exemplar of the New York branch of independent filmmaking. The larger demons of Hollywood proper are kept at a distance.

Along the way, the book, written with Anthony Kaufman, covers Hope’s work with a wide range of filmmakers, many at the beginnings of their careers, including Hartley, Ang Lee, Ed Burns, Todd Solondz and Todd Field. Hope produced James Gunn (who most recently directed the big-budget smash “Guardians of the Galaxy”) on the earlier indie-scaled “Super.” He recalls adventures with filmmakers Nicole Holofcener and Tamara Jenkins, while repeatedly noting the ongoing need for more women in the directing ranks and the difficulties faced by even the most acclaimed female filmmakers.

The book is full of behind-the-scenes anecdotes that mix grit, gumption and charm. In one of the book’s best chapters, Hope captures the ways the personal and professional intertwined in his career while recalling the production of Jenkins’ 2007 film, “The Savages,” which received two Academy Award nominations. Jenkins and Hope had dated for a time before working together, and throughout the process of making the film he second guesses her motives and his own: How much are they are acting out of concern for the project, and how much of their working relationship involves reliving their personal dynamic? Something as simple as an actress’ wig can become a fraught matrix of money, ego and emotions. In a rather uproarious digression, Hope describes attending Jenkins’ wedding to writer and producer Jim Taylor, where he ends up accidentally spilling wine on another of Jenkins’ exes. The book could, in all honesty, have used more moments like that.

It seems at times that Hope shies away from talking about the intersection of his professional and personal lives, perhaps out of discretion for others. Some of his more recent projects, such as the micro-budget gems “Martha Marcy May Marlene” and “Starlet,” are skimmed over.

More than that, this seems like a lost opportunity to discuss the shifting landscape of the film industry, how those projects functioned in relation to the current environment and the changing role of a producer like himself. The ambitious self-distribution of Solondz’s recent “Dark Horse” might have provided a springboard for consideration of where the business is heading.

The chronology of the book is a bit of a jumble, as projects from the 1990s and 2000s are recounted out of linear order, making it hard to trace the larger arcs of the industry along with Hope’s own development. And the chapter recounting Hope’s seemingly tumultuous yearlong stint as executive director of the San Francisco Film Society, ending in late 2013, feels out of step with the reflective tone of the rest of the book. It reads like someone angrily recounting all the tiny details of a recent breakup. Yet out of that comes his most recent incarnation, as chief executive of the online streaming service Fandor.

The final section of the book finds Hope in full proselytizer mode, dealing with many of the issues of production and distribution he regularly talks about via social media and the small network of blogs he oversees. Hope’s story is ultimately one of renewal, because he argues that there will always be a need for cinematic storytelling, even as the definitions of those terms change.

Although it may not function as an ultimate handbook or history for independent filmmaking, “Hope for Film” suggests that as long as there are passionate advocates and deeply invested, long-term thinkers like Hope, there is hope for cinema and a future for filmmaking. (MCT)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Weekender] Geeks have never been so chic in Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050845_0.jpg&u=)

![[News Focus] Mystery deepens after hundreds of cat deaths in S. Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/17/20240517050800_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Byun Yo-han's 'unlikable' character is result of calculated acting](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050855_0.jpg&u=)

![[Photo News] Seoul seeks 'best sleeper'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/18/20240518050098_0.jpg&u=)