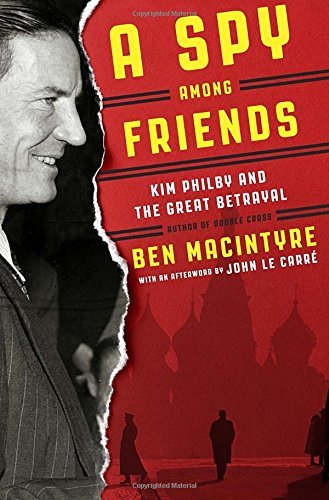

By Ben Macintyre

(Crown)

A lot of spy novels would have you believe that espionage involves elite globe-trotting adventures laced with good booze and cool toys, and certainly there are elements of all those things in Ben Macintyre’s vivid and fascinating new “A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal.” But this nonfiction book’s most intense scene is prosaic ― two old friends, middle-aged English gentlemen who came up as spies through British intelligence, share a cup of tea while “lying courteously to each other” in a Beirut apartment in 1963.

Some authors would turn that moment into literary Ambien. But in Macintyre’s hands, it hums. “As night falls, the strange and lethal duel continues, between two men bonded by class, club and education but divided by ideology; two men of almost identical tastes and upbringing but conflicting loyalties; the most intimate of enemies,” he writes. “To an eavesdropper their conversation appears exquisitely genteel, an ancient English ritual played out in a foreign land; in reality it is an unsparing, bare-knuckle fight, the death throes of a bloodied friendship.”

One of those men was H.A.R. “Kim” Philby. Aptly nicknamed after the Rudyard Kipling character who had a foot in two worlds, Philby was perhaps the greatest and most notorious double agent in history. For almost three decades, beginning in the mid-1930s, this quintessential upper-class Englishman worked as a Soviet spy in British intelligence, passing information to Moscow that would cost the lives of at least hundreds, if not thousands, while crippling British and American intelligence operations. “I don’t know that the damage he did can ever be actually calculated,” wrote former CIA director Richard Helms.

The other man having tea in that Beirut apartment was Nicholas Elliott, and about the only thing he didn’t have in common with Philby was his allegiance. Both men, Macintyre tells us, were raised by nannies, and both formed their identities at Britain’s finest schools ― Philby at Eton, Elliott at Westminster. Both loved a good, wet evening out. Philby once polished off 52 brandies in a single evening with a friend, and Elliott once saved a waitress by dousing her with “three glasses of white wine” after a flambe attempt gone awry.

Perhaps most importantly, both men possessed that particular English charm, a quality that most found “intoxicating, beguiling” and some learned could be “occasionally lethal.” When one potential British asset met Elliott for the first time, for instance, he “felt almost as if (his) feet rested already on English soil.” And Philby, Macintyre writes, “could inspire and convey affection with such ease that few ever noticed they were being charmed.”

It’s perhaps this quality, along with his social status, that made Philby’s betrayal all that much harder to detect, especially for Elliott. “Elliott hero worshipped Philby, but he also loved him,” Macintyre writes.

Philby’s story has been covered before in several biographies and other Cold War espionage accounts. Macintyre’s aim here is to describe instead the “very British relationship” between these two men. He succeeds admirably. The book feels so thoroughly British, you may wonder if it’s bound with Marmite. Macintyre calls one botched operation an “unmitigated, gale-force cock-up.” The culture at MI6, he says, “was White’s Club; MI5 was the Rotary Club.”

Hints about Philby’s true loyalties surfaced occasionally throughout his career, but it wasn’t until 1963 that Elliott was presented with irrefutable evidence that his friend was a traitor. Elliott confronted him in that Beirut apartment, and Philby subsequently managed to escape to Russia, where he lived until 1988 as a symbol of the Soviet cause. They even honored him on a postage stamp. Some claim Elliott allowed his old friend to flee. Others believe Elliott was duped, which Macintyre thinks unlikely.

One thing is certain: Elliott tried for the last laugh. When Philby died, Elliott recommended that his old pal posthumously receive the sixth-most-prestigious award in the British honor system, “awarded to men and women who render extraordinary or important nonmilitary service in a foreign country,” along with a signed obituary that would call Philby the bravest man he had ever known. “The implication would be clear to Moscow: Philby had been acting for Britain all along.”

The proposal was denied. By that point, it seems, “old boy” pranks, however brilliant, were a thing of the past. “The new-style MI6,” Macintyre writes, “did not do jokes.” (MCT)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)