By Mac Griswold

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

When the line of cars waiting for the Shelter Island ferry stretches halfway to Sag Harbor, it is hard to imagine that this popular Long Island vacation spot was once considered the very edge of European civilization. But in 1653, when Nathaniel Sylvester purchased Shelter Island from the Manhansett tribe, his goal was not to build a summer home but to establish a plantation much like those in the Southern colonies to provision European holdings in the West Indies with food, livestock and barrels for rum.

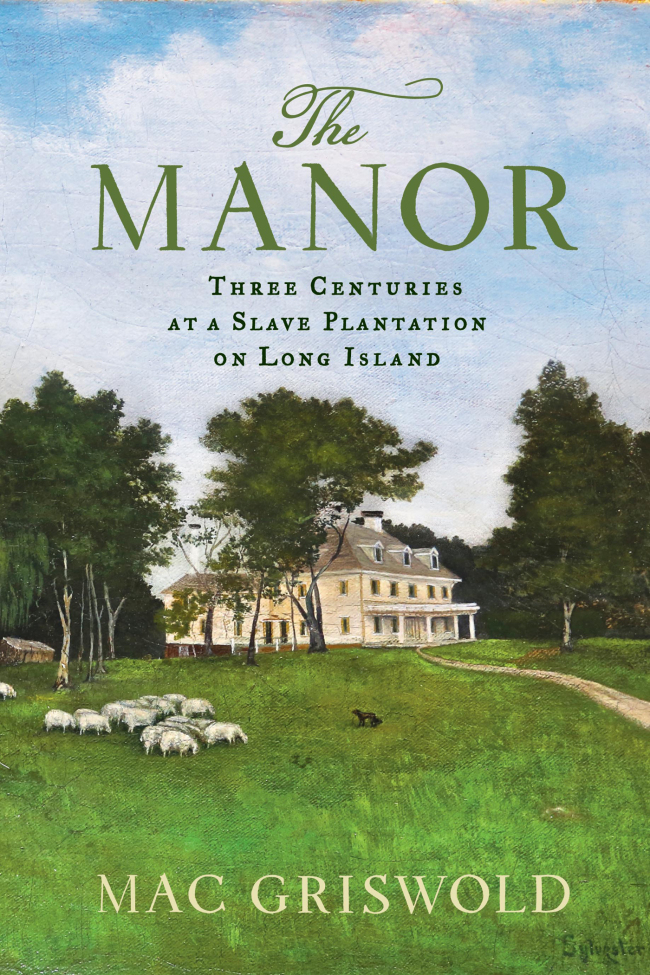

To do so, Sylvester enlisted the island’s native inhabitants and imported enslaved Africans. Colonists, Indians and slaves lived in uneasy relation to one another during what landscape historian Mac Griswold calls a “highly experimental period of European settlement.” Sylvester’s will refers to 22 slaves as property at the time of his death in 1680. After reading Griswold’s haunting new study, “The Manor: Three Centuries at a Slave Plantation on Long Island,” it is difficult not to see the ghosts of 17th century colonists, native Manhansetts and enslaved Africans mingling with the summer crowds.

Griswold first viewed the stately manor house while kayaking on Gardiners Creek in 1984. A sighting of the towering boxwoods, started from seedlings brought over from England by Sylvester’s wife, sparks her interest in the history of this hidden place. She befriends the current residents, Sylvester descendant Andrew Fiske and his wife, Alice, who show her the house, with its staircase to the former slave quarters in the attic, and the grounds, featuring a slave graveyard. The Fiskes let her poke around a messy study filled with historical documents pertaining to the house’s history, including the Sylvester family’s intriguing conversion to Quakerism even as they continued to acquire slaves. Griswold is shocked when confronted with the evidence of Northern slavery, and even more shocked to learn that by the mid-18th century, “Long Islanders owned more human chattel than any other group of colonists in the North.” (MCT)

After Andrew Fiske’s death, Griswold helps Alice Fiske arrange for a team of University of Massachusetts archaeologists to excavate the property. And that is when the story really gets interesting. Through artifacts, including ceramics, coins and bricks, Griswold is able to speculate on the “struggles over power and the use of space” at the Manor. Shell fragments left over from wampum production indicate the Manhansetts, working for the Sylvesters, produced the common currency for the family in a kind of backyard mint. Pottery shards from vessels fired at very high temperatures indicate that one or more of the plantation’s slaves brought knowledge of African smelting and ironworking techniques. According to the archaeological record, every aspect of Colonial life on Shelter Island was marked by the oppression of American Indians and Africans. (There are no records of conditions there.)

Even after the 1827 abolition of slavery in New York, its specter lingered. In 1848, the Manor passed to Mary Gardiner and her husband Eben Horsford. Staunch Union supporters, the Horsfords, nonetheless, romanticized the manor’s past and benefited from their role as benevolent masters. A Montauket named Isaac Pharaoh, formerly indentured to Mary’s father, lived out his life at the manor, sleeping by the kitchen fire in the winter, as a “sort of court jester to the Sylvester Manor family, the least threatening and best loved of Indians.” Their black housekeeper, Julia Dyd Havens Johnson, the daughter of freed slaves, was treated respectfully by the Horsfords as a “relic” who “embodied for them a resolution to the great conflict that had nearly torn the nation apart.” But records show that in 1865 Johnson sold 10 acres of waterfront property that she had inherited from her parents to the Horsfords for less than half the market rate, so Eben could develop a summer resort.

Long Islanders curious about the history of the land we now occupy will be moved by Griswold’s layered account, which continues to the present day. It is now possible to tour the manor itself, and experience what Griswold calls the “supernatural, magnetic strangeness that every visitor to Sylvester Manor feels.” Run more as a kibbutz than a plantation, the nonprofit Sylvester Manor Educational Farm attracts unpaid volunteers to grow organic vegetables for shareholders. The archaeological dig continues, with a plan to uncover the footprints of more than 80 early buildings and evidence of the forgotten people who worked the land. In acknowledgment of the inequities of its past, the farm has adopted a new slogan: “With a spirit of fairness and joy.” (MCT)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[H.eco Forum] H.eco Forum calls for transition to clean, carbon-free energy](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/22/20240522050668_0.jpg&u=20240522175145)

![[Exclusive] LACMA admits it needs further research on donated Korean paintings](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/22/20240522050568_0.jpg&u=20240523001632)

![[Bridge to Africa] Africa-Korea partnership: Why it matters for future](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/22/20240522050681_0.jpg&u=20240522182351)

![[Herald Interview] Korean adoptees embark on journeys to find roots](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/22/20240522050754_0.jpg&u=20240522190539)

![[Graphic News] Medical tourists visiting Korea reach record high](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/21/20240521050794_0.gif&u=20240523171313)

![[Today’s K-pop] NCT127 drops single in Japan to mark anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/05/23/20240523050694_0.jpg&u=20240523175657)