Not forgotten: Former POW recounts his ordeal in the North

By Korea HeraldPublished : June 21, 2013 - 20:45

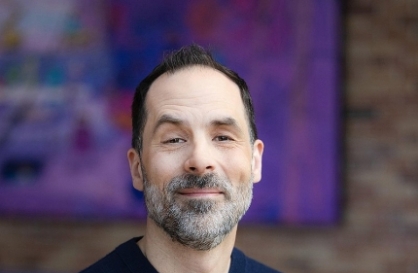

After nearly 50 years of harsh labor in North Korea, Yu Young-bok, a former prisoner of war, returned to Seoul in 2000.

The city looked like a utopia with posh cars, skyscrapers and life free from hunger and oppression. Yu was fortunate to reunite with his father, then 94, just six months before he died.

But the euphoria faded quickly as he began to feel guilty for those whom he had left behind. His children would face the harsher oppression that North Korea inflicted on “traitors.” His fellow POWs would still be tormented at notorious underground mines waiting hopelessly to reunite with their loved ones in the South.

The city looked like a utopia with posh cars, skyscrapers and life free from hunger and oppression. Yu was fortunate to reunite with his father, then 94, just six months before he died.

But the euphoria faded quickly as he began to feel guilty for those whom he had left behind. His children would face the harsher oppression that North Korea inflicted on “traitors.” His fellow POWs would still be tormented at notorious underground mines waiting hopelessly to reunite with their loved ones in the South.

“No words can sufficiently describe the humiliating, grueling life we went through in those mines ― a thousand meters underground. Some were shot dead or sent to political prisons for protesting,” Yu, 84, told The Korea Herald.

“Thinking of my comrades still there, I just can’t sit back and enjoy this freedom. That is why I have become an outspoken advocate for their rights and their safe return,” said Yu, who is an honorary president of the Family Union of Korean POWs Detained in North Korea.

The former Army private was captured by the Chinese during a fierce border battle in Geumhwa, Gangwon Province, in June 1953, a month before the armistice halted the three-year Korean War on July 27 of that year.

The first major Cold War conflict left at least 4 million soldiers and civilians dead.

Tens of thousands of South Korean soldiers are believed to have been taken prisoner by North Korea.

Seoul estimates some 500 of them are currently alive in the North. Yu is among the 80 POWs who fled to the South. As of May, 29 of them have died.

“We, POWs, all waited for the Seoul government to come liberate us from the pain. We believed it would not leave us there like that for good. A decade, two decades … four decades of yearning to return home were all in vain,” he said.

Hopes were revived when former President Kim Dae-jung made a landmark visit to Pyongyang in 2000 for the first inter-Korean summit, which set out a multitude of exchanges and humanitarian projects across the border.

“We anxiously hoped we would follow him, but there was no word about the resolution of our issue. Then, I decided to cross the border, even at the age of 71,” he said.

He spent most of his time in the North toiling at remote, underground mines under the watchful eye of merciless armed guards.

More painful, however, was that he had to see his son and daughter going through the same discrimination as him, labeled “reactionary elements” by the communists.

The veteran’s voice was trembling when he recalled his family ordeal. His wife died of malnutrition six years before he left the North. In 2010, he brought his son, daughter-in-law and grandson to the South. But his daughter still lives in the North.

“My entire family suffered indescribable discrimination. Our children could not go to college, enter the Workers’ Party nor do anything to work up the social pecking order,” he said.

“Some of the family members of the POWs were given citizenship, but they were obviously intended to cajole them into joining difficult national projects.”

After two generations of ignorance, their fate has become a major government agenda. Yu welcomed the move but said it might be too late due to their old age.

“Do you think the POWs in their 80s with their families there would be willing to come here alone even if you give them tens of billions of won?”

“But it is crucial for the government to send a clear message to current soldiers and their parents that the nation would save them if they are taken captive. Otherwise, who would willingly send their kids to the frontline, when the Koreas remain technically at war?”

Seoul has put the humanitarian issue high on its policy agenda and sought diplomatic cooperation with Beijing to ensure the safety of the POWs who entered its territory.

But returned POWs and families of those remaining in the North demand the government should act more aggressively to account for them and bring them back.

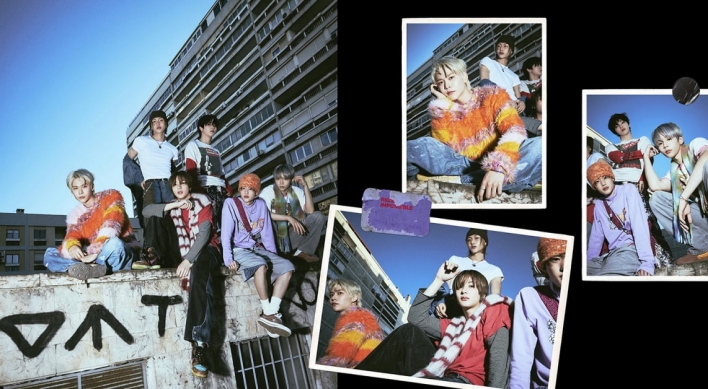

On the vanguard in the campaign is the Family Union of Korean POWs Detained in North Korea, led by North Korean defector Lee Ju-won.

The son of a South Korean POW, Lee, 44, also suffered from ruthless discrimination in the North.

“When I entered elementary school at age 7, I realized I was a son of a POW as my classmates laughed at me, calling me a son of the puppet military’s prisoner of war.” he told The Korea Herald.

His peers kept spitting on him and his shoulders were always wet, he recalled, fighting back tears.

“Our family had no hope whatsoever for any better life. I was supposed to go to the coal mine upon graduation to do what my father had done and our entry to the military, higher education, party and any decent workplace was virtually blocked.”

Lee first crossed the border with China in 1997, but was caught by Chinese police and repatriated on several occasions. In September 2008, he summoned the courage again to escape to China and finally made it to Seoul with his wife and son in January 2009.

He said one of the toughest times in the North was when his sister was forced to marry a man 15 years older than her, as his father wanted her not to bequeath the POW family background to her children.

“POW fathers did not want their daughters to repeat the arduous life as POW families. So they sent them to any men with good pedigrees or social backgrounds, no matter how old they were and regardless of whether they were healthy or not,” he said.

“My sister married an older party member who beat her and led her to leave home. She then developed some mental disorder.”

Lee is now free from persecution, but potent memories of his father’s agony still haunt him. His father died in 1994, two months after he retired from four decades of labor at a mine.

“My father regained freedom only after death,” he said. “His life was more frightful than any Korean and U.S. horror movie as he didn’t know whether he could live tomorrow under the 24/7 surveillance of the state minders.”

He also remembered his father wept when the reclusive regime kept saying South Korea was one of the world’s poorest states with highly outdated governing systems.

“My father wept in the corner of the room, saying his loved ones in the South might have died of hunger and bad living conditions as the regime’s anti-South Korea propaganda machine spoke ill of it,” he said.

“We just believed it as it was said back then. My father would have felt happy if he had known that (it was all lies).”

Like other North Korean refugees, the biggest concern for Lee is the family and relatives he left behind in the North. The regime punishes defectors’ families for “betraying the fatherland.” His 83-year-old mother and two sisters are still in the North.

“I always pray for my old mother. We have this deep sorrow that cannot be healed, and thus we can’t just be happy with what we can enjoy in this free, democratic society.”

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald