Native English teacher head count continues decline

As regional programs continue phaseouts, competence of Korean teachers called into question

By Korea HeraldPublished : May 1, 2013 - 20:48

This is the first in a two-part follow-up series to one which was published in the Expat Living section on March 6 and 13 and covered the ongoing native English teacher phaseouts in certain regions nationwide. This series further assesses the native English teacher program as well as the Teaching English in English initiative for Korean teachers of English in primary and secondary public schools. Intern reporters Choi In-jeong, Lee Sang-ju and Suh Hye-rim contributed to this series. ― Ed.

The number of native English teachers in public elementary and secondary schools this year dropped for the second consecutive year to about 7,000, according to data gathered by The Korea Herald.

Regional budget restructuring as well as assessments of the native English teacher program’s effectiveness and Korean teachers’ English-speaking competence have led to wide-scale cuts, especially in middle and high schools.

The Ministry of Education has been unable to release a total head count or budget estimate, as none of the 17 city and provincial offices of education submitted their data by the April 29 deadline, an official from the ministry said Wednesday.

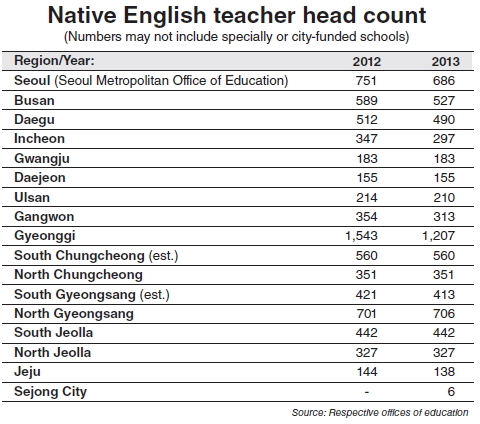

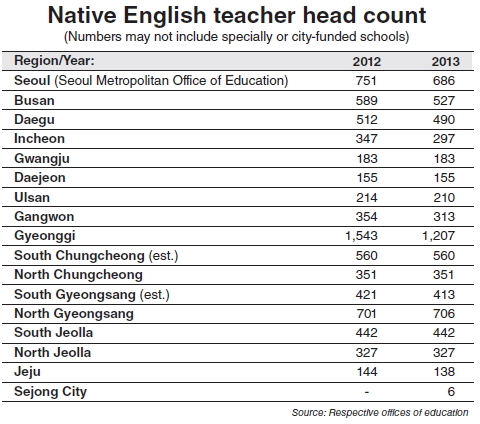

However, according to estimates given to The Korea Herald by each of the respective regional education offices, the total number of native English teachers decreased by some 583 from last year to 7,011. All but two offices of education ― Sejong City, which kicked off the program this year, and North Gyeongsang Province, where a boarding school is expanding ― said that their numbers either stood the same or declined. The figures may not include specially or city-funded schools.

The combined figure is down about 7.7 percent from 7,594 teachers in 2012, though a total of 8,520 native English teachers were employed in public schools last year including other budgets. The Ministry of Education estimated that 340.8 billion won ($309.5 million) was spent on native English teacher programs nationwide, but could not yet provide an estimate for the 2013 school year, which started at the beginning of March.

Rise and fall

Since 1995, the English Program in Korea and later regional programs in Seoul City and Gyeonggi and South Jeolla provinces have brought teachers from English-speaking countries into the nation’s public schools to practice conversation skills, enhance Korean teachers’ English skills and introduce foreign cultures to students. The programs grew rapidly, hiring 59 in 1995 and peaking at 8,798 teachers in 2011.

Teachers have promoted the native English teacher program for providing native expressions and nuances and fresh perspectives to engage students to learn English not as a school subject, but as a language and part of culture. Surveys by Seoul National University have shown that about twice as many students pay more attention in native English teacher-led classes than ones led by Korean teachers.

Paul Jambor, an assistant professor of English for academic purposes at Korea University, said that his incoming freshmen had become increasingly more accepting of his classroom’s English-only, communicative atmosphere over the years.

“The influence of NETs in Korea has certainly had an effect ... in my students’ increasing willingness, as compared to 11 years ago, to shift toward a learner-centered environment, being immersed in a communicative context.”

The number of native English teachers in public elementary and secondary schools this year dropped for the second consecutive year to about 7,000, according to data gathered by The Korea Herald.

Regional budget restructuring as well as assessments of the native English teacher program’s effectiveness and Korean teachers’ English-speaking competence have led to wide-scale cuts, especially in middle and high schools.

The Ministry of Education has been unable to release a total head count or budget estimate, as none of the 17 city and provincial offices of education submitted their data by the April 29 deadline, an official from the ministry said Wednesday.

However, according to estimates given to The Korea Herald by each of the respective regional education offices, the total number of native English teachers decreased by some 583 from last year to 7,011. All but two offices of education ― Sejong City, which kicked off the program this year, and North Gyeongsang Province, where a boarding school is expanding ― said that their numbers either stood the same or declined. The figures may not include specially or city-funded schools.

The combined figure is down about 7.7 percent from 7,594 teachers in 2012, though a total of 8,520 native English teachers were employed in public schools last year including other budgets. The Ministry of Education estimated that 340.8 billion won ($309.5 million) was spent on native English teacher programs nationwide, but could not yet provide an estimate for the 2013 school year, which started at the beginning of March.

Rise and fall

Since 1995, the English Program in Korea and later regional programs in Seoul City and Gyeonggi and South Jeolla provinces have brought teachers from English-speaking countries into the nation’s public schools to practice conversation skills, enhance Korean teachers’ English skills and introduce foreign cultures to students. The programs grew rapidly, hiring 59 in 1995 and peaking at 8,798 teachers in 2011.

Teachers have promoted the native English teacher program for providing native expressions and nuances and fresh perspectives to engage students to learn English not as a school subject, but as a language and part of culture. Surveys by Seoul National University have shown that about twice as many students pay more attention in native English teacher-led classes than ones led by Korean teachers.

Paul Jambor, an assistant professor of English for academic purposes at Korea University, said that his incoming freshmen had become increasingly more accepting of his classroom’s English-only, communicative atmosphere over the years.

“The influence of NETs in Korea has certainly had an effect ... in my students’ increasing willingness, as compared to 11 years ago, to shift toward a learner-centered environment, being immersed in a communicative context.”

But at the same time, he and other education experts criticize the quality of the overall public English curriculum for poorly preparing students for real-world English use, neglecting vital skills such as writing and speaking, and instead placing too much focus on preparing for college entrance exams.

In Jambor’s class, his incoming freshmen experience a “culture shock” when they realize the level of English they need in English-led university classes far exceeds what they learned up to high school.

“With the growing trend of elite Korean universities determined to offer an increasing number of English-mediated lectures, students are finding it ever more difficult to do well in programs requiring a high degree of English language competence, particularly in the case of top Korean universities,” he said, noting that at top schools such as POSTECH, KAIST and Yonsei University’s Underwood International College, 50-100 percent of undergraduate classes are conducted in English.

His students even expressed low satisfaction (20-40 percent) for how well their high school prepared them for university, according to a survey he gave his classes last year.

Education pundits argue that the quality of Korea’s public English education has become more than an educational issue, but also a social one, preparing students to successfully integrate into a highly demanding and increasingly globalized society. At the same time, they acknowledge that the gap between those who can and can’t afford private education is widening, despite the government’s efforts to curb the influence of hagwon.

But amid further budget constraints, policymakers face the challenge of balancing their budget and meeting the demands for high-quality public education for all students.

Structural problems

The native English teacher program was intended to bring an extra facet to make curriculums more practical and communication-oriented, but teachers argue that structural problems get in the way of making the most of it.

Classes with native English teachers don’t benefit the low-level students who can’t understand them, said Lee Eun-kyung, an English teacher at Shinan Middle School in Gyeonggi Province who has co-taught with NETs for more than seven years.

“Some high-level English students are utilizing the NET program fairly well, but for students who have below-average English proficiency, the NET program is not helping them that much,” she said.

“Native English teachers don’t know what to teach in low-level classes and Korean English teachers usually translate during the entire class instead of teaching. This is not ideal education-wise.”

While that might be true, says Lee Hyun-jung, a 20-year veteran English teacher at Kwonsun Elementary School in Gyeonggi Province who is teaching with a native English teacher for her fourth year, low-level students would fall even more behind without a native English teacher.

“If schools stop supporting NET classes, low-level students will not have learning opportunities with NETs at all,” she said. “And when there is a native English teacher in the classroom, I can see more students trying to speak in English than when they do in the normal English class with only Korean English teachers.”

But, NETs, who are generally contracted to teach 22 classes per week, are usually unable to cover all the English classes of a whole school, noted Lee of Shinan Middle School. With such busy schedules, it’s difficult for native teachers to spend one-on-one time or strike up conversation with students, she said.

She, among others, also said that “NETs don’t prepare for the classes as much as they are supposed to.” Another teacher suggested this is sometimes because they feel like they should only play an assistant role to their Korean co-teacher.

A supervisor from the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education said that as native English teachers tended to change schools frequently, it was difficult to secure qualified teachers.

NETs’ experiences also vary greatly, as some teachers come fresh out of college with unrelated degrees, while others have several years of teaching experience. The government is attempting to boost the qualifications of native teachers by requiring those in public schools to attain a teaching certificate. As of 2012, 4,849 of them, or 56.9 percent, held some type of teaching certification, according to the Education Ministry.

Choi Hye-jung, a Seoul teacher who heads her high school’s English department, said that the bigger problem is not who the teacher is, but class size. Even with a native English teacher, with 40 students in a class the teacher can only have average effectiveness, she noted.

The Ministry of Education leaves it up to provincial and city governments to decide how many native English teachers to employ. Gyeonggi Province began reducing its number of secondary school NETs in 2009 except in rural areas, and handing the classes over to Korean teachers it deems English-proficient. In Seoul City, a total phaseout excluding specialized schools was announced in late 2011 with a 2014 completion date, and officials say it is running as scheduled. Both regions still utilize native English teachers in elementary schools.

“In mid-2012, there was an evaluation that (Korean) English teachers were doing well enough that we could reduce the number of NETs,” a Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education official, who asked to not be named, told The Korea Herald.

“Of course, it would be good to have NETs if we had the budget; however, there is no need to force it since there are constraints.”

The office had previously stated that 95.6 percent of its Korean English teachers had attained a “Teaching English in English capacity” by the end of 2011. The SMOE said it spent 42.2 billion won on 751 NETs last year, which does not include specially or privately funded schools, and estimated a 31.2 billion won budget for 686 teachers this year.

On the other hand, less populated areas with lower foreign populations such as Daejeon and Gwangju cities and South Jeolla and North Gyeongsang provinces have said they aim to hold onto their small NET programs and even enhance them.

The Ministry of Education estimated that local governments spent 341.8 billion won on native English teachers in 2010, 351.9 billion won in 2011 and 340.8 billion won in 2012.

Shoes to fill

Regardless of Korean teachers’ feelings toward NETs in the classroom, budget restrictions among other factors have forced some education offices to restructure their English programs ― by reducing numbers of NETs and tapping English-proficient Korean teachers to take their place.

But policymakers face one major hurdle: It is claimed that today’s Korean teachers cannot fill the demand for high-quality education with their current skill sets.

“Despite various efforts made by the teachers, teacher educators and policymakers, the issue of the language teaching competence of the Korean teachers of English has been critically raised by the general public and has become a social issue as well as an educational one,” said Lee Hyo-shin, a professor at Konkuk University, noting that the goal of English education was to give students the communicative competence required in today’s global society.

A major reason behind the low English-speaking abilities of many teachers is their own grammar-intensive schooling, which paid far less attention to conversation skills than the classes they now teach, education observers say.

“A significant portion of middle school and high school teachers simply do not possess the necessary English knowledge to be able to teach academic English to their students at the required level,” Jambor of Korea University said.

Further, elementary-level English teachers are often not trained to teach the language as schools traditionally reshuffle teachers between grades and subjects each year as they see fit.

So as budgets and policy changes leave schools with little choice but to depend on domestic teachers, Seoul has ramped up its efforts to make its Korean teachers of English competent enough to confidently and effectively lead a class focusing on writing and speaking skills ― with or without a native English teacher.

In 2009 Seoul City initiated a program to boost current Korean teachers’ capabilities to both speak English and do so while teaching. Under the Teaching English in English program, teachers undergo intensive training for weeks or months and are then tested on their English teaching knowledge and ability.

“When the TEE certification started in 2009, there was an evaluation that students’ English skills were poor. That pointed out the English teachers’ poor English skills,” the SMOE official said.

“The purpose of TEE certification is not to make teachers study English, but to modify how they teach English so students can enjoy learning and improve students’ conversation skills.”

The TEE program continues today in Seoul and has been adapted in regions throughout the nation. By 2011, an estimated 1,500 teachers nationwide had participated, and the SMOE told The Korea Herald that 1,324 teachers in Seoul passed through its certification as of February 2013.

Many teachers say the program, though difficult, has definitely improved their English skills and given them the confidence to lead classes in English.

But the program is mired with troubles, ranging from lack of interest among secondary-level and older generations of teachers in participating, to instructors and judges claiming that evaluations are rigged to pass teachers who don’t deserve certification. Observers argue that the objectives and even the scorecards are too vague for TEE to be an effective standard for teachers’ English capacity.

With limited budgets, under-skilled teachers and rising competition with the private sector, are education policymakers preparing Korean teachers enough to teach English effectively in the absence of native English teachers?

By Elaine Ramirez (elaine@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)