TOKYO (AFP) ― An extremely rare copy of a work by fourth century Chinese calligraphy legend Wang Xizhi has been unearthed in Japan, the first such discovery in four decades, Tokyo National Museum said Tuesday.

No original works survive, despite their having been treasured by Chinese emperors throughout history for their contribution to the development of the delicate art form.

However, Wang’s innovative style was so influential that Chinese courts created precise replicas of his writings more than a millennium ago, some of which are held by Japan as national treasures.

No original works survive, despite their having been treasured by Chinese emperors throughout history for their contribution to the development of the delicate art form.

However, Wang’s innovative style was so influential that Chinese courts created precise replicas of his writings more than a millennium ago, some of which are held by Japan as national treasures.

“This is a significant discovery for the study of Wang Xizhi’s work,” the museum, which will display it from Jan. 22 to March 3, said in a statement.

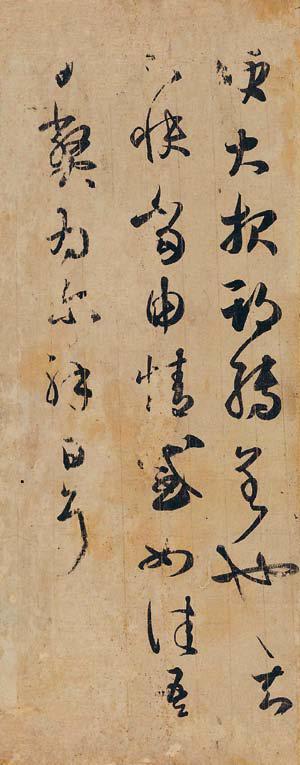

The writing, owned by an individual in Japan whose identity was not disclosed, shows 24 Chinese characters in three lines on a piece of paper roughly 26 centimetres by 10 centimeters.

It was long thought to be the work of an ancient Japanese nobleman calligrapher, but a recent review by Jun Tomita, Chinese calligraphy expert at the museum, has determined that it was an expertly-made copy of Wang’s writing.

The page appears to be part of a letter and includes phrases known to be used by the master calligrapher.

“I am tired everyday. I am living only for you,” part of the script says.

It also includes the names of his relatives including his son, the museum said.

The content of the writing, its style, copying technique, and other factors indicate the copy was made during the Tang Dynasty in the seventh to eighth century by the emperor’s court, the museum said.

It was likely brought out of China by Japanese commercial or diplomatic missions visiting their powerful continental neighbour during the same era, the museum said.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Up close in Yeouido] Trump hinting at US troop removal in South Korea ‘election-time talk’](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/05/21/20240521050695_0.jpg&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hong Kong rally spurs hope for ELS loss mitigation](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/05/21/20240521050686_0.jpg&u=)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids hit Billboard’s Hot 100 with Charlie Puth collab](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/05/21/20240521050699_0.jpg&u=20240521182133)