New resettlement center opens for N.K. defectors

Second Hanawon to host growing number of refugees, provide resettlement education

By Korea HeraldPublished : Dec. 5, 2012 - 20:10

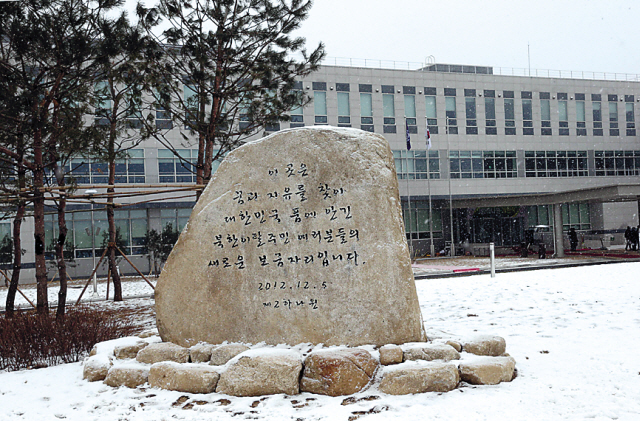

A new resettlement center for North Korean defectors opened on Wednesday to accommodate a growing influx of refugees and provide improved assimilation education and support.

Located in Hwacheon, Gangwon Province, the second Hanawon will house up to 500 people in 10 units in a 15,000-square-meter area, increasing the total hosting capacity to 1,100 across the country.

“The new resettlement center was built to prepare ourselves for the steadily increasing defector inflow and carry out advanced education,” the Unification Ministry said in a statement.

The ministry is in charge of protection and training at five such institutions including the first Hanawon center, which opened in 1999 in Anseong, Gyeonggi Province, to help asylum seekers adapt to the capitalist South and stand on their own feet. Under a 1997 North Korean refugee law, the central and local governments provide support in housing, education and job training.

The government has poured 34 billion won ($31.4 million) into establishing the new facility since July 2011.

It will offer not only the mandatory three-month training but also reeducation for graduates and upper-level lessons for highly educated North Koreans, the ministry said.

The new center will also facilitate programs for male defectors, while the first Hanawon continues to serve women and children. The ministry had been striving for segregated training in line with U.N. recommendations.

The project reflects a recent surge in North Koreans who cross the border to escape hunger and oppression in their homeland.

Located in Hwacheon, Gangwon Province, the second Hanawon will house up to 500 people in 10 units in a 15,000-square-meter area, increasing the total hosting capacity to 1,100 across the country.

“The new resettlement center was built to prepare ourselves for the steadily increasing defector inflow and carry out advanced education,” the Unification Ministry said in a statement.

The ministry is in charge of protection and training at five such institutions including the first Hanawon center, which opened in 1999 in Anseong, Gyeonggi Province, to help asylum seekers adapt to the capitalist South and stand on their own feet. Under a 1997 North Korean refugee law, the central and local governments provide support in housing, education and job training.

The government has poured 34 billion won ($31.4 million) into establishing the new facility since July 2011.

It will offer not only the mandatory three-month training but also reeducation for graduates and upper-level lessons for highly educated North Koreans, the ministry said.

The new center will also facilitate programs for male defectors, while the first Hanawon continues to serve women and children. The ministry had been striving for segregated training in line with U.N. recommendations.

The project reflects a recent surge in North Koreans who cross the border to escape hunger and oppression in their homeland.

Despite tightening border controls and harsh penalties, the annual tally has been hovering between 2,400 and 3,000 since 2007, ministry data shows. Nearly 70 percent are female and about 74 percent are younger than 50.

More than 2,700 North Koreans took refuge here last year, up about 12.7 percent from a year ago. The collective figure has topped 24,300 since the 1950-53 Korean War.

Officials expect the exodus to persist in the coming years. Seoul estimates that tens of thousands of North Koreans are hiding in China currently aspiring to move into the South and other countries.

The ministry has expanded the Hanawon center twice before, in 2003 and 2008, increasing the capacity from the initial 150 people to 600. It is expected to transfer services from three other smaller branches running in rented spaces on the outskirts of Seoul to cut costs and stabilize operation.

The ministry is also providing 5.7 billion won to build a stadium at Hanawon as early as the end of 2013 to improve trainees’ health and promote various programs.

However, the plan for the new Hanawon met with stiff public opposition since the site selection process in early 2009.

A bulk of 24 candidate towns witnessed the rise of the “not-in-my-backyard” movement. Residents in some regions furiously claimed that they would not let their children study in the same class with the offspring of “red commies.”

After talks with government officials and touring the first Hanawon, opponents eventually changed their minds and started seeing advantages the facility may bring, ministry officials said.

“There was an atmosphere in which people saw the resettlement center as a place like a refugee camp or prison,” a ministry official said on condition of anonymity.

Seoul’s overall defector policy has also been subject to debate as critics cast doubt on its effectiveness, saying that many Hanawon graduates are still struggling to adjust here.

The government offers each defector 19 million won for resettlement, in addition to financial aid worth up to 21.4 million won for vocational training and preparation.

Other support programs include health insurance and subsidies for low-income earners.

The ministry’s defector-related spending neared 124 billion won this year, taking up about 60 percent of its entire budget. With expenses by provincial governments taken into account, its share of public coffers should be much greater.

Still, defectors here have reported a wide range of social and financial problems. Cultural and educational gaps could take years to overcome. Prejudice among South Koreans is another factor as politics and ideology frame them despite their ethnicity.

“It still remains questionable whether the public fund is well distributed to actually improve the livelihoods of the defectors,” said Ahn Chan-il, director of the World North Korea Research Center who defected to the South in 1979, in an earlier interview with The Korea Herald.

“The authorities are trying to increase the number of counseling centers, resting places and other facilities with state organizations trying to yield good achievements from them. It is just window dressing, not welcomed by the defectors.”

A 2011 survey of 8,299 defectors by the North Korean Refugees Foundation showed that more than 30 percent earn less than 1 million won a month. Their jobless rate averaged 12.1 percent ― more than triple the population’s 3.7 percent.

Some opt to head for a third country such as the U.S., Britain or Australia, seeking to access a better social safety net and to break free from social exclusion and cutthroat competition with better-off, highly educated South Koreans in an already saturated job market.

In extreme cases, at least five defectors returned to their impoverished homeland and held news conferences this year, stoking speculation and concerns over their resettlement and adaptability here.

But others emphasize that no matter how much state money is given, defectors should also make substantive efforts to be self-reliant.

“Everyone goes through a period of adjusting to cultural differences, social prejudice and so on,” said Kang Chul-ho, a Christian minister who fled the North in 1992.

“But more importantly, you’d better strive to learn and get used to the society you are in. How can the government take care of so many defectors forever?”

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Robert J. Fouser] Social attitudes toward language proficiency](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050799_0.jpg&u=)

![[Graphic News] How much do Korean adults read?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050803_0.gif&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Byun Yo-han's 'unlikable' character is result of calculated acting](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050855_0.jpg&u=)