Subscribe for shirts, buy brand-name goods online

Subscription e-commerce and private shopping clubs emerge in Korea after the boom of social commerce

By Korea HeraldPublished : Nov. 9, 2012 - 20:29

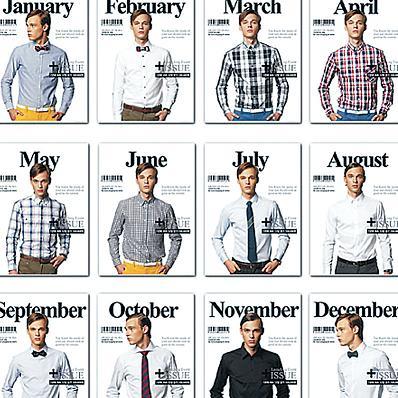

Online shopping mall Shirts Magazine offers subscriptions for shirts, not magazines ― literally.

For 100,000 won a year, you get a crisp new shirt delivered to your home every month. It’s like having your monthly-subscribed magazine in your mailbox. And you get to choose the color and design each month from a range of choices on the net.

“I got the subscription for my husband,” says housewife Lee, who only wished to reveal her last name. Her husband is an urban professional in Seoul, who is required to wear suits to work every day.

“It’s a lot cheaper this way. You end up spending about 8,000 won for each shirt, while it usually costs about 30,000 or 40,000 won in department stores. For office workers like my husband, it’s impossible not to buy shirts. It’s something you need every day, like rice or kimchi. So this subscription works perfectly.”

For 100,000 won a year, you get a crisp new shirt delivered to your home every month. It’s like having your monthly-subscribed magazine in your mailbox. And you get to choose the color and design each month from a range of choices on the net.

“I got the subscription for my husband,” says housewife Lee, who only wished to reveal her last name. Her husband is an urban professional in Seoul, who is required to wear suits to work every day.

“It’s a lot cheaper this way. You end up spending about 8,000 won for each shirt, while it usually costs about 30,000 or 40,000 won in department stores. For office workers like my husband, it’s impossible not to buy shirts. It’s something you need every day, like rice or kimchi. So this subscription works perfectly.”

“Shirts Magazine” is one of several new entrants to subscription e-commerce in Korea, which used to be dominated by beauty and fashion products.

The very first firm of its kind in the country, Glossy Box opened its website in June last year; it offers a “beauty subscription” service, which consists of sending a box of beauty products, randomly chosen by the service organizers, to its customers on a regular basis.

Each and every month, they’d send something different. For one month, the box’s items would include a bottle of Dr. Bronner’s cleansing oil. A month later, one would receive a box consisting of a bottle of Clarins cream and Kenzo perfume. The firm only received 1,500 orders in July of last year, but the number of orders hit 12,000 by December.

Unlike Glossy Box, which aims to surprise its customers by not letting them know what’s in the delivered boxes in advance, Shirts Magazine aims to attract customers with specific needs. It also takes a different approach from fashion subscription e-commerce firms, such as Memelook.

Currently on a temporary hiatus, Memelook has enjoyed popularity for its unique subscription service since its launch in May. The service consisted of sending one or two pieces of clothes, selected by “fashion experts,” each month, for a monthly fee of 20,000 won. Its customers get to find out what each month’s featured items are on 25th of every month.

“The main difference of our service is that we let our customers choose the exact shirt that they want before they get delivered,” said Kim Mi-young, promoter for Shirts Magazine.

“Shirts belong to the category of fashion, but they are also consumables for most urban professionals. You always end up needing new shirts anyway, which is why we thought of shirts when launching the subscription business. You get what you need at your door, after choosing what you want online in advance.”

The service opened last month as a sub-division of membership commerce site Zero Lounge. The site currently has 5,000 registered members, and about 50 customers sign up for the yearly subscription online every day, according to Kim. Most of its customers are men in their 30s, and women of the same age who seem to purchase the service for their spouses, she said.

Other consumable products, such as razors, diapers and flowers, are sold by subscription e-commerce firms in the U.S. For example, American arts and craft company Kiwi Crate sells subscription craft projects for children online. It keeps its young customers engaged by continuously sending new boxes of craft projects before they can get bored with the old ones.

Internet shopping is nothing new in Korea, where almost everything can be purchased online and delivered to your house.

The industry entered its new phase with the sudden boom in social commerce businesses last year. The social commerce industry alone has grown into a 1 trillion won market in the last two years.

Online sites of firms like Coupang, Ticket Monster and Groupon Korea would offer discounts of 50 percent or more, as long as the customer brings in a certain number of fellow buyers through SNS. Their products would range from cosmetics to concert tickets and tour packages to Hong Kong and Tokyo.

Following the popularity of social commerce is online private shopping clubs, where customers get a 50 percent discount or more by signing up for the membership. Their products are usually much higher-end, such as Givenchy bags, Gucci wallets and Dior and Chanel sunglasses.

Club Venit, a local online private shopping club, has almost 19,000 members on its Facebook page. It first launched in October of last year, and its sales have increased more than 10-fold since then, according to its management. About 70 percent of its 170,000 members are women aged 27 to 34.

“They were our main target from the very beginning,” said Noh Taeho from Club Venit. “We aimed to attract women who have the money for those brand-name goods but don’t have the time to hit department stores.”

The shopping club was founded after studying the case of Vente-privee.com, a popular French e-commerce company which pioneered an online environment to host members-only sales in which consumers can purchase high-end designer goods at substantial discounts from retail prices. The company celebrated its 10th anniversary last year. Club Venit also studied the U.S. online shopping mall Gilt Groupe, which offers a very similar online service.

“Vente-privee and Gilt actually have a longer history than business models of social commerce,” said Noh from Club Venit.

“We thought a business model like these two companies would have a chance in the local market. One of the challenges was that most designer-brand goods are from overseas. Vente-privee and Gilt often deal with local products, while we have to get them from overseas.”

Club Venit’s offers are hard to resist. Its members can purchase a Mulberry Alexa oversize shoulder bag for 1.35 million won with a 39 percent discount, while its retail price is 2.185 million won. An Emporio Armani watch would cost 295,000 won with a 52 percent discount, while it would be about 612,000 won for the same item at a physical store.

“It has to do with the retail margins,” said Noh. “We house the goods in about three different locations of ours, and there are almost no distribution charges and no retail margins to cover. That’s how these sales events are possible online.”

Yet some people still may enjoy the experience of physically being in a store, examining the products, and the feeling of bringing the purchased goods to home.

“Well, it’s all about the image,” says Park Hee-chul, director of major hair salon chain By Miga, which runs its members-only website for customers to purchase the hairstyle they want before physically arriving to the shop.

“When people buy things online, they are not only buying the products. They are buying the image of them carrying the bag, wearing the watch, or with the new haircut.”

By Miga, which opened in 2008 with a single shop in Hongdae, now runs eight other branches thanks to the success of its membership-based website.

A By Miga member does not have to worry about getting a bad haircut, or getting a perm that’s totally different from what they asked for. Instead, they go on the salon’s website, browse through the different styles, and purchase whatever they like in advance ― guaranteed to get the look in the photo.

When Park first launched the site in October 2008, he only made 70,000 won that month.

“We had to force one of our family friends to use the website to make some kind of profit,” said Park. “In the beginning, they thought of it as making a reservation online. But it’s totally different from that.”

Now, more 60 percent of By Miga customers use the website; the salon’s sales increased by “several hundred-fold.”

“I wanted to sell style online,” said Park. “Whether your products are tangible or intangible, it’s the image that matters in the online world.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[AtoZ Korean Mind] Does your job define who you are? Should it?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/06/20240506050099_0.jpg&u=)