A 30-year-old newly-wed employee of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) is bitter about the ongoing relocation of key government offices to Sejong City, located some 150 kilometers south of Seoul.

The female civil servant, who asked to be known only as Park, deliberately got pregnant years before she initially planned to take advantage of government rules that allow years of maternity leave, thus delaying her move to Sejong.

Park said she feels relieved after hearing of the ordeals suffered by colleagues, including being isolated in Sejong away from family and friends in Seoul, or spending as many as six hours commuting to and from the new administrative town in central South Korea.

Under the government’s project to create an administrative hub in Sejong, a total of 10,452 officials at 16 central government offices and 20 subsidiary organizations currently located in or near Seoul, are to move to Sejong by 2014, in phases. About 120 officials belonging to six departments of the PMO became the first to relocate over the weekend.

Park said she gave up the honeymoon phase of her marriage to hastily have a baby so as to not immediately “be separated from family members” in Seoul.

“I married a couple of years ago, and originally planned to have a baby years later, to first enjoy couple time with my husband. But we changed our plan upon learning that I had to go to Sejong in December,” she said, while cradling her 2-month-old baby.

“To fully support my child, both I and my husband have to make money, but I don’t want my daughter to stay only with either her mom or her dad. During my maternity leave, I’ll discuss with my husband what we should do in the future,” she said.

South Korean employees are entitled by law to three months of paid maternity leave and one year of paid parental leave.

Government officials can also take up to a further two years unpaid leave.

The move to Sejong project comes 10 years after Roh Moo-hyun, then the opposition presidential candidate, made an election pledge to build a new administrative capital in the central region, to promote balanced regional development and ease the overpopulation in Seoul and nearby regions. Seoul is home to a fifth of the country’s population of 50 million.

Park is not alone in her dilemma. A large number of government workers set to move to the new city have been struggling to come up how to keep their families together.

A 37-year-old PMO official has had to rise almost two hours earlier since Monday when his office moved to Sejong, and he has quit his gym workouts.

“I opted for everyday commuting as my family cannot move together to Sejong. My wife works in Seoul, and my daughter in her first year of elementary school has just adapted to her school life,” the official said. He declined to be identified.

“I have to spend some five hours each day to go to and from work, more than twice as long as before. I thought it would be fine, as I can sleep or read books on the way. But after three days, I am not sure how long I can continue to do so,” he said.

A trip from his home in Gwangjin, eastern Seoul, to Seoul Station takes about 40 minutes by subway. From Seoul Station to Osong, the nearest station to Sejong, takes about an hour by high-speed train. He then has to take a 15-minute bus ride to the government buildings. With transfers and waiting time, his daily commute totals about five hours.

“I chose commuting to spend more time with my family, but the opposite seems to be the case as I am so exhausted by the daily five-hour trip.”

Last year, more than 40 officials working for central government agencies applied for transfers to the Seoul Metropolitan Government, an increase from seven such cases a year earlier, according to the municipal government.

“We have a regular personnel exchange program between local governments and the central government, but last year’s surge was unusual. The relocation plan seems to be behind the phenomenon,” said Koo Ah-mi, who is in charge of the city’s personnel matters.

Failing to find methods to stay with their family members, however, almost four of each 10 officials said they would move to Sejong alone.

In the survey conducted by the PMO in April of 10,576 officials scheduled to transfer to the new city, 51.86 percent, or 5,485 officials, said they will move to the city with their families, 37 percent would move alone, and 12 percent planned to commute each day from current residences mostly in Seoul or the surrounding regions.

Among those planning to move with family members, one third would not be accompanied by their complete family, the survey showed.

“Primary concerns among the officials include their spouses’ work and education for their children, along with a lack of basic infrastructure as the city is in the first stage of its construction,” said Kim Jung-min, PMO’s deputy minister in charge of supporting the government relocation project.

“I’ve just become a goose father,” said a 46-year-old PMO official and father of two who declined to be identified. “It is like a 21st-century version of a separated family.”

The term goose father is used in South Korea to describe men separated from their children and wives, usually as the wife and children go abroad for education. In recent years, large numbers of South Korean women have accompanied their children overseas, leaving the husbands behind to support them financially.

“My elder daughter is preparing for her college entrance exam, and my son goes to middle school,” the official said. “I am thinking of bringing my wife and second child to Sejong City sometime next year, but my wife is saying no, citing the better educational opportunities in Seoul for my son.”

“Many of my colleagues, particularly mid-age male officials, made the same choice as mine. For a father in this country, sacrificing oneself is the only option.”

Such concerns are not confined only to married public servants.

A mid-level female worker at the finance ministry said she plans to move near Gwangmyeong Station, south of Seoul, when she begins working in the new city later this year. Gwangmyeong is one of the major stations for a high-speed train linking Seoul and Sejong,

“I am 33 years old, and hope to get married soon,” she said, also requesting anonymity. “But the relocation plan will kill my chances to find a fiance due to the limited pool of single men in the closed city.”

“A single person like me has a double whammy, as I have to move away from my family and at the same time am deprived of opportunities to set up a new family after getting married.”

The government has devised measures to support officials who move to Sejong, including tax incentives for those who buy apartments there, transportation services that link the city’s government complex to major nearby stations and Seoul, and pushing for extensive exchanges of officials to allow couples to work in the new city together.

For single officials, the government held a match-making event in April to help them find potential spouses. That “is expected to help them better settle down in the new city, though the one-off event went nowhere,” said Jung Ui-seok, a PMO official who devised the project.

The measures seem far from enough to dispel concerns about a new life in unfamiliar and inconvenient circumstances and away from a support network of family and friends.

“Currently, I go to a yoga academy twice a week and learn English conversation on Saturdays,” said an official from the Tax Tribunal, who is preparing to move in November. “I would have more time to spend alone in Sejong, but I heard there are not even basic facilities such as retail stores and general hospitals, let alone those for hobbies or other leisure activities.”

Such a lack is already reality for some officials and their families in the new city.

“I was excited to lead a new life in Sejong and in the first ever apartment of my own,” said a 40-year-old housewife and mother of two, who moved to Sejong in August with her husband, who works for the PMO. “My hometown is Daejeon, not far from here, and I heard that residents would enjoy diverse, state-of-the-art facilities together with nature.

”But look around here. No cinemas, no restaurants, no academies for my children. As construction is underway everywhere, I’m even afraid of opening the windows due to the dust and noise,“ she said.

”I am mulling whether to move into my parents’ home until the city is equipped with at least a basic infrastructure. I came here to stay together with my husband and children, but now I suspect a separate family life seems my destiny,“ she said.

”The government nicknamed Sejong the “Happy City,” but nobody seems happy for now. The situation is too difficult and uncertain to enjoy any excitement as an early settler.”

(Yonhap News)

The female civil servant, who asked to be known only as Park, deliberately got pregnant years before she initially planned to take advantage of government rules that allow years of maternity leave, thus delaying her move to Sejong.

Park said she feels relieved after hearing of the ordeals suffered by colleagues, including being isolated in Sejong away from family and friends in Seoul, or spending as many as six hours commuting to and from the new administrative town in central South Korea.

Under the government’s project to create an administrative hub in Sejong, a total of 10,452 officials at 16 central government offices and 20 subsidiary organizations currently located in or near Seoul, are to move to Sejong by 2014, in phases. About 120 officials belonging to six departments of the PMO became the first to relocate over the weekend.

Park said she gave up the honeymoon phase of her marriage to hastily have a baby so as to not immediately “be separated from family members” in Seoul.

“I married a couple of years ago, and originally planned to have a baby years later, to first enjoy couple time with my husband. But we changed our plan upon learning that I had to go to Sejong in December,” she said, while cradling her 2-month-old baby.

“To fully support my child, both I and my husband have to make money, but I don’t want my daughter to stay only with either her mom or her dad. During my maternity leave, I’ll discuss with my husband what we should do in the future,” she said.

South Korean employees are entitled by law to three months of paid maternity leave and one year of paid parental leave.

Government officials can also take up to a further two years unpaid leave.

The move to Sejong project comes 10 years after Roh Moo-hyun, then the opposition presidential candidate, made an election pledge to build a new administrative capital in the central region, to promote balanced regional development and ease the overpopulation in Seoul and nearby regions. Seoul is home to a fifth of the country’s population of 50 million.

Park is not alone in her dilemma. A large number of government workers set to move to the new city have been struggling to come up how to keep their families together.

A 37-year-old PMO official has had to rise almost two hours earlier since Monday when his office moved to Sejong, and he has quit his gym workouts.

“I opted for everyday commuting as my family cannot move together to Sejong. My wife works in Seoul, and my daughter in her first year of elementary school has just adapted to her school life,” the official said. He declined to be identified.

“I have to spend some five hours each day to go to and from work, more than twice as long as before. I thought it would be fine, as I can sleep or read books on the way. But after three days, I am not sure how long I can continue to do so,” he said.

A trip from his home in Gwangjin, eastern Seoul, to Seoul Station takes about 40 minutes by subway. From Seoul Station to Osong, the nearest station to Sejong, takes about an hour by high-speed train. He then has to take a 15-minute bus ride to the government buildings. With transfers and waiting time, his daily commute totals about five hours.

“I chose commuting to spend more time with my family, but the opposite seems to be the case as I am so exhausted by the daily five-hour trip.”

Last year, more than 40 officials working for central government agencies applied for transfers to the Seoul Metropolitan Government, an increase from seven such cases a year earlier, according to the municipal government.

“We have a regular personnel exchange program between local governments and the central government, but last year’s surge was unusual. The relocation plan seems to be behind the phenomenon,” said Koo Ah-mi, who is in charge of the city’s personnel matters.

Failing to find methods to stay with their family members, however, almost four of each 10 officials said they would move to Sejong alone.

In the survey conducted by the PMO in April of 10,576 officials scheduled to transfer to the new city, 51.86 percent, or 5,485 officials, said they will move to the city with their families, 37 percent would move alone, and 12 percent planned to commute each day from current residences mostly in Seoul or the surrounding regions.

Among those planning to move with family members, one third would not be accompanied by their complete family, the survey showed.

“Primary concerns among the officials include their spouses’ work and education for their children, along with a lack of basic infrastructure as the city is in the first stage of its construction,” said Kim Jung-min, PMO’s deputy minister in charge of supporting the government relocation project.

“I’ve just become a goose father,” said a 46-year-old PMO official and father of two who declined to be identified. “It is like a 21st-century version of a separated family.”

The term goose father is used in South Korea to describe men separated from their children and wives, usually as the wife and children go abroad for education. In recent years, large numbers of South Korean women have accompanied their children overseas, leaving the husbands behind to support them financially.

“My elder daughter is preparing for her college entrance exam, and my son goes to middle school,” the official said. “I am thinking of bringing my wife and second child to Sejong City sometime next year, but my wife is saying no, citing the better educational opportunities in Seoul for my son.”

“Many of my colleagues, particularly mid-age male officials, made the same choice as mine. For a father in this country, sacrificing oneself is the only option.”

Such concerns are not confined only to married public servants.

A mid-level female worker at the finance ministry said she plans to move near Gwangmyeong Station, south of Seoul, when she begins working in the new city later this year. Gwangmyeong is one of the major stations for a high-speed train linking Seoul and Sejong,

“I am 33 years old, and hope to get married soon,” she said, also requesting anonymity. “But the relocation plan will kill my chances to find a fiance due to the limited pool of single men in the closed city.”

“A single person like me has a double whammy, as I have to move away from my family and at the same time am deprived of opportunities to set up a new family after getting married.”

The government has devised measures to support officials who move to Sejong, including tax incentives for those who buy apartments there, transportation services that link the city’s government complex to major nearby stations and Seoul, and pushing for extensive exchanges of officials to allow couples to work in the new city together.

For single officials, the government held a match-making event in April to help them find potential spouses. That “is expected to help them better settle down in the new city, though the one-off event went nowhere,” said Jung Ui-seok, a PMO official who devised the project.

The measures seem far from enough to dispel concerns about a new life in unfamiliar and inconvenient circumstances and away from a support network of family and friends.

“Currently, I go to a yoga academy twice a week and learn English conversation on Saturdays,” said an official from the Tax Tribunal, who is preparing to move in November. “I would have more time to spend alone in Sejong, but I heard there are not even basic facilities such as retail stores and general hospitals, let alone those for hobbies or other leisure activities.”

Such a lack is already reality for some officials and their families in the new city.

“I was excited to lead a new life in Sejong and in the first ever apartment of my own,” said a 40-year-old housewife and mother of two, who moved to Sejong in August with her husband, who works for the PMO. “My hometown is Daejeon, not far from here, and I heard that residents would enjoy diverse, state-of-the-art facilities together with nature.

”But look around here. No cinemas, no restaurants, no academies for my children. As construction is underway everywhere, I’m even afraid of opening the windows due to the dust and noise,“ she said.

”I am mulling whether to move into my parents’ home until the city is equipped with at least a basic infrastructure. I came here to stay together with my husband and children, but now I suspect a separate family life seems my destiny,“ she said.

”The government nicknamed Sejong the “Happy City,” but nobody seems happy for now. The situation is too difficult and uncertain to enjoy any excitement as an early settler.”

(Yonhap News)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] Mom’s Touch seeks to replicate success in Japan](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050568_0.jpg&u=)

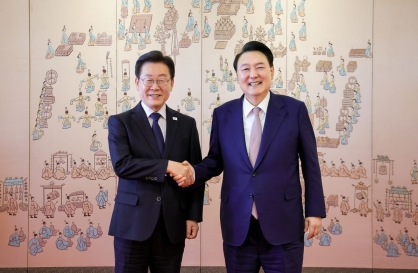

![[News Focus] Lee tells Yoon that he has governed without political dialogue](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050696_0.jpg&u=20240429210658)

![[Today’s K-pop] Seventeen sets sales record with best-of album](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/30/20240430050818_0.jpg&u=)