Education in South Korea is attracting increasing attention worldwide. South Korean students’ excellent performance on the Program for International Students Assessment is often taken as an indicator of the achievement of South Korean education. President Barack Obama of the United States likes to point to Korea as an example that American schools should emulate in order to solve the pressing problems facing their educational system.

The astonishing pace at which the Korean school system grew mirrors the equally unprecedented speed of Korean economic development. Various statistical indicators show that, at least in the area of education, South Korea is an undisputed leader, outperforming the size of its economy. Not only does the country boast the world’s highest rates of enrollment, but it also has the lowest dropout rate in the world. However, these stellar outward achievements are not enough to offset the complaints of students and parents inside the system.

Historically, the expansion of the school system in Korea accompanied an increasing interest in admission into high schools and universities. The major issue that faced the Korean education policymakers in the past was to expand opportunities for learning by opening up an increasing number of schools as well as providing financial aid for struggling students. With almost all Korean children and teenagers enrolled in schools today, however, mere admission into high schools or universities no longer command pressing concerns. The public attention is now on improving the quality, not the quantity, of education. The problem is that qualitative growth is not as easy to achieve. It is much more difficult to produce or experience noticeable, tangible growth in the quality of education in proportion to the investment of resources and efforts than to see quantitative expansion.

There are also disagreements as to what constitutes qualitative, as opposed to quantitative, improvement. Furthermore, the typically high expectations the Korean public has of its school system as the potential source of answers to all social ills make it even more difficult to decide on the direction in which Korean education should progress.

Many Koreans are also putting forward diverse opinions based on their personal experiences. It is perhaps worthwhile, however, to turn our focus outward at this point and try to identify a number of features that have been crucial to the improvement of quality in education worldwide.

The first such key feature is ensuring individual students’ access to the different types of education they require. A national curriculum standardized and enforced single-handedly by the central government belongs in the past. What is important today is to provide individuated, specialized curricula for students of different needs, circumstances and learning characteristics. A keyword for the practitioners of education reform in Korea today is therefore “diversity.”

Second, while diversity and individuality in education are certainly important, education should also serve as a bridge for social integration and solidarity. What distinguishes public school systems from private tutoring is that the former purports to serve public interests. In other words, the public school system ought to provide an education that caters to public values over and beyond the conflicts among different interest groups. Moreover, actual fields of education ought to provide opportunities for individuals of diverse backgrounds to come and grow together in recognition of their mutual interdependence. In the terminology of education reform, this need is captured by such slogans as the “equality of education” and “community values.”

Many countries around the world are now actively searching for ways to bring these two seemingly contradictory values into harmony. In order to enhance diversity at schools, a government may either diversify the range of public schools, or expand the curricular operating system so as to allow for greater flexibility in catering to the increasing demand for diversification.

The Korean government has adopted the former policy. This policy has so far allowed individual schools to diversify their curricula to cater to the specific needs of their respective student bodies. There are an increasing number of critics, however, who point out that this policy of diversification has in fact served to enhance class stratification more than the cause of diversity. As students from certain socioeconomic backgrounds tend to concentrate on certain schools, it has become increasingly difficult for students of different backgrounds to mingle together and share a common experience.

To address these concerns and criticisms effectively, it is important to develop a new system that diversifies schools in response to the special demands from certain students, while also allowing each school to develop its own system taking into account the diverse characteristics of its student body. In other words, we need to allow diverse groups of students to interact with and understand one another while attending the same schools. This new approach is certainly more difficult to practice than the diversification of schools. When applied to all public schools in Korea, the new approach may turn out to require quite burdensome investment. It may also require corresponding changes in the policy for hiring and arranging the teaching staff.

Educational reform must start with a long-term view of what future society has in store for us. Future society is not some distant, uncertain realm that we cannot predict, but will be in part shaped by the difficulties, problems and potential that our students are experiencing in the present.

One core problem facing today’s students, and especially significant for the future, is the limitation inherent in teaching various subjects as mere knowledge. This problem ought to be addressed, because what matters is not how much students know as a result of attending schools, but how much they internalize their learning and turn it into capabilities for the future. Researchers provide a list of these capabilities, including the ability to express oneself, to communicate with others, and so forth. The curricula of the past naturally allowed students to acquire these capabilities by attending schools.

Students today, however, have fewer opportunities to get to know one another and build friendships through in-person interactions, as they increasingly resort more and more to computers and the Internet to form relationships or to pass the time in the virtual world of online games. This is why there is a greater emphasis on helping students acquire abilities to form real-life relationships and perform more effective communication. This need becomes greater when one considers how Korean students, who score the highest on the PISA, also rank almost at the bottom in terms of cooperation.

In other words, our task is to develop institutional and practical measures that respect the diversity and individuality of students. At the same time, however, we must ensure that diverse groups of students communicate with, understand and relate to one another out of an increasing sense of social solidarity and community.

The astonishing pace at which the Korean school system grew mirrors the equally unprecedented speed of Korean economic development. Various statistical indicators show that, at least in the area of education, South Korea is an undisputed leader, outperforming the size of its economy. Not only does the country boast the world’s highest rates of enrollment, but it also has the lowest dropout rate in the world. However, these stellar outward achievements are not enough to offset the complaints of students and parents inside the system.

Historically, the expansion of the school system in Korea accompanied an increasing interest in admission into high schools and universities. The major issue that faced the Korean education policymakers in the past was to expand opportunities for learning by opening up an increasing number of schools as well as providing financial aid for struggling students. With almost all Korean children and teenagers enrolled in schools today, however, mere admission into high schools or universities no longer command pressing concerns. The public attention is now on improving the quality, not the quantity, of education. The problem is that qualitative growth is not as easy to achieve. It is much more difficult to produce or experience noticeable, tangible growth in the quality of education in proportion to the investment of resources and efforts than to see quantitative expansion.

There are also disagreements as to what constitutes qualitative, as opposed to quantitative, improvement. Furthermore, the typically high expectations the Korean public has of its school system as the potential source of answers to all social ills make it even more difficult to decide on the direction in which Korean education should progress.

Many Koreans are also putting forward diverse opinions based on their personal experiences. It is perhaps worthwhile, however, to turn our focus outward at this point and try to identify a number of features that have been crucial to the improvement of quality in education worldwide.

The first such key feature is ensuring individual students’ access to the different types of education they require. A national curriculum standardized and enforced single-handedly by the central government belongs in the past. What is important today is to provide individuated, specialized curricula for students of different needs, circumstances and learning characteristics. A keyword for the practitioners of education reform in Korea today is therefore “diversity.”

Second, while diversity and individuality in education are certainly important, education should also serve as a bridge for social integration and solidarity. What distinguishes public school systems from private tutoring is that the former purports to serve public interests. In other words, the public school system ought to provide an education that caters to public values over and beyond the conflicts among different interest groups. Moreover, actual fields of education ought to provide opportunities for individuals of diverse backgrounds to come and grow together in recognition of their mutual interdependence. In the terminology of education reform, this need is captured by such slogans as the “equality of education” and “community values.”

Many countries around the world are now actively searching for ways to bring these two seemingly contradictory values into harmony. In order to enhance diversity at schools, a government may either diversify the range of public schools, or expand the curricular operating system so as to allow for greater flexibility in catering to the increasing demand for diversification.

The Korean government has adopted the former policy. This policy has so far allowed individual schools to diversify their curricula to cater to the specific needs of their respective student bodies. There are an increasing number of critics, however, who point out that this policy of diversification has in fact served to enhance class stratification more than the cause of diversity. As students from certain socioeconomic backgrounds tend to concentrate on certain schools, it has become increasingly difficult for students of different backgrounds to mingle together and share a common experience.

To address these concerns and criticisms effectively, it is important to develop a new system that diversifies schools in response to the special demands from certain students, while also allowing each school to develop its own system taking into account the diverse characteristics of its student body. In other words, we need to allow diverse groups of students to interact with and understand one another while attending the same schools. This new approach is certainly more difficult to practice than the diversification of schools. When applied to all public schools in Korea, the new approach may turn out to require quite burdensome investment. It may also require corresponding changes in the policy for hiring and arranging the teaching staff.

Educational reform must start with a long-term view of what future society has in store for us. Future society is not some distant, uncertain realm that we cannot predict, but will be in part shaped by the difficulties, problems and potential that our students are experiencing in the present.

One core problem facing today’s students, and especially significant for the future, is the limitation inherent in teaching various subjects as mere knowledge. This problem ought to be addressed, because what matters is not how much students know as a result of attending schools, but how much they internalize their learning and turn it into capabilities for the future. Researchers provide a list of these capabilities, including the ability to express oneself, to communicate with others, and so forth. The curricula of the past naturally allowed students to acquire these capabilities by attending schools.

Students today, however, have fewer opportunities to get to know one another and build friendships through in-person interactions, as they increasingly resort more and more to computers and the Internet to form relationships or to pass the time in the virtual world of online games. This is why there is a greater emphasis on helping students acquire abilities to form real-life relationships and perform more effective communication. This need becomes greater when one considers how Korean students, who score the highest on the PISA, also rank almost at the bottom in terms of cooperation.

In other words, our task is to develop institutional and practical measures that respect the diversity and individuality of students. At the same time, however, we must ensure that diverse groups of students communicate with, understand and relate to one another out of an increasing sense of social solidarity and community.

By Ryu Bang-ran

Ryu Bang-ran is a senior research fellow at the Korean Educational Development Institute. ― Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Grace Kao] Hybe vs. Ador: Inspiration, imitation and plagiarism](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/28/20240428050220_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Mom’s Touch seeks to replicate success in Japan](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050568_0.jpg&u=)

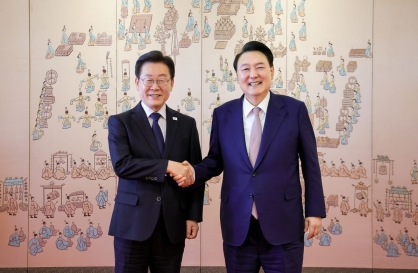

![[News Focus] Lee tells Yoon that he has governed without political dialogue](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/29/20240429050696_0.jpg&u=20240429210658)

![[Today’s K-pop] Seventeen sets sales record with best-of album](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/30/20240430050818_0.jpg&u=)