Korean, black communities move on, learning from racial confrontation

By Korea HeraldPublished : May 10, 2012 - 19:39

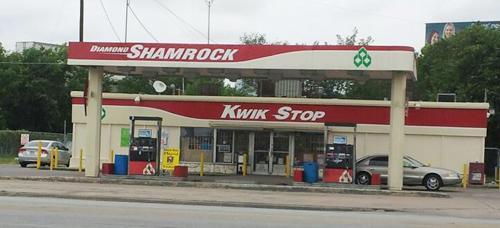

DALLAS, Texas (Yonhap News) ― Korean-American Thomas Pak had little idea of the ensuing storm that would be sparked by the encounter last December inside his South Dallas gas station with African-American Jeffrey Muhammad.

Their exchange was relatively brief, but if some accounts are to be believed, it was also angry and weighed down by racial overtones.

And it launched a months-long boycott of Pak’s business by members of the largely African-American community. Corralled outside his premises, they urged people passing by not to give the 40-year-old their patronage.

Why? Pak’s December exchange with Muhammad, they said, was the work of a man who racially slurred one of their own. What’s more, the story went, a year previously Pak shot dead a young black man who had robbed his store.

Their exchange was relatively brief, but if some accounts are to be believed, it was also angry and weighed down by racial overtones.

And it launched a months-long boycott of Pak’s business by members of the largely African-American community. Corralled outside his premises, they urged people passing by not to give the 40-year-old their patronage.

Why? Pak’s December exchange with Muhammad, they said, was the work of a man who racially slurred one of their own. What’s more, the story went, a year previously Pak shot dead a young black man who had robbed his store.

Pak made identical claims of racist jibes lobbed in the other direction. As for the shooting, someone was indeed shot and killed after robbing Pak’s store, but, according to local reports, Pak was not the shooter and no charges were ever leveled after the incident was declared a case of self-defense. Much later, at least one media outlet, the Dallas Observer, would print a story essentially outing Muhammad as a liar who conned many members of the local black community into joining a protest orchestrated to further the cause of the fringe group he represents, the Nation of Islam, itself plagued by allegations it is a black supremacist organ.

In other circumstances, Pak’s encounter with Muhammad might have passed by with neither fanfare nor publicity.

But it didn’t. And, aside of the rights and wrongs of the affair, it left two communities facing some uncomfortable questions. On a deeper level, it brought to the fore the touchy issue of race relations in the United States. So much so that Charles Park, one of the eldest Korean community leaders in Dallas, immediately recalled the Koreatown, Los Angeles, riots of 1992, whose 20th anniversary lingered ominously on the horizon as the protest played out. “My concern was that there are quite a lot of Koreans doing business in South Dallas,” he recalls.

The main protester argument in economically deprived South Dallas focused on the suggestion Koreans were the latest in a long line of ethnic groups who sweep into predominantly black neighborhoods, sucking out resources. There are reportedly anywhere between 700 and 2,000 Korean-owned businesses in South Dallas.

“The idea of one group exploiting another group of people has been around for some time,” says Mark Keam, the first ever Korean-American delegate in the Virginia state legislature. “The fact it happens means certain stereotypes come into play.”

Those stereotypes, he believes, are the key to understanding why racially charged expletives and derogatory terms were traded between Pak and Muhammad. Part of the problem, he suggests, comes from a complex mix of 50-plus-year-old Koreans who are educated but don’t speak English, finding themselves surrounded by people they consider lesser-educated. For the African-Americans living in the communities where Korean-owned businesses set up, there tends to be a feeling that money is taken away from their areas by people who do not even live there.

Among Koreans, he says, “there is more of a class-based attitude”; among blacks “a strong sense of resentment and inequality.”

“It’s not a question of changing one person’s mind,” Keam reckons. “It’s a question of education.”

Greg Howard, a reporter at the Dallas Observer who covered the protest, sees things through a similar prism. “What you see is basically two populations of people who have been disenfranchised,” he says.

In urban areas like South Dallas, he goes on, black communities who have been there for generations and have been fighting inequality for hundreds of years see a wave of more recent immigrants ― in this case Korean ― moving into their areas and robbing them of what they view as “opportunity.”

“They are like, ‘This is not fair. Why don’t we have these shops,’” observes Howard, himself black. “I disagree with this because there is a belief that what Jeffrey Muhammad said ― that white power gives money to Koreans to exploit blacks ― that is not how a business survives. But these are still the conclusions people are coming to.”

On this point a number of actors in the dispute seem to now agree: that ordinary people who took part in the protest were duped and exploited.

After the South Dallas protest began to peter out, calls quickly came for increased dialogue between the two communities. A Korean diplomat was dispatched to intervene. Korean community leaders including Park and Ted Kim, vice president of the Korean Society of Dallas, held joint meetings and a press conference that eventually led to detente. Detente has since, say Park and Kim, given way to reaching out. That is something that has been found wanting in the past, says Howard, an absence of “you know where I am coming from, and I know where you are coming from.”

“We want to send black people to Korea to learn about our culture,” says Kim. “We (Koreans) were at one time enslaved. Our women were taken (during the Japanese colonial period). We have rebounded from that. Now we have one of the most powerful economies in the world.”

In return, members of the black community have pledged to help their Korean counterparts with political organization, he adds, something that is not necessarily a Korean strength in the U.S.

Joint events are planned. Korean businessmen have pledged to help fund scholarships worth tens of thousands of dollars, says Kim.

Virginia politician Keam goes further. “The more people from different backgrounds, the more we should look at people as individuals, and get rid of the traditional notions of race.”

Park, the Dallas Korean community elder, meanwhile, heaved a sigh of relief after the joint meetings led to signs of rapprochement. “The word crisis in Korean letters is two characters,” he says. “One is danger or hazardous, but the other is opportunity. So a crisis is considered a danger, but also gives us the opportunity to make it up. We finally got together with the black community leaders, hand in hand, prayed together and now we are getting closer and closer.“

Local press outlets afforded space to acknowledge the early in-roads. Nevertheless, some observers remain cautious. Howard of the Dallas Observer says he would love to envisage a time when Koreans and blacks in South Dallas go into business together. But, he concedes, “we are a long way off from that.”

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Weekender] Geeks have never been so chic in Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050845_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Byun Yo-han's 'unlikable' character is result of calculated acting](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050855_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Byun Yo-han's 'unlikable' character is result of calculated acting](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/05/16/20240516050855_0.jpg&u=)