South Korea needs to grasp China’s tendency to put priority on practical interests

Seoul officials had wished the ceremony would be held with much more fanfare.

They had envisioned top leaders from South Korea and China attending the launch of a series of events scheduled throughout this year to mark the 20th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between the two countries.

To their disappointment, both sides were represented by vice culture ministers at the ceremony in the National Museum of Korea in Seoul on April 3, which drew little attention from news media here.

According to sources familiar with the matter, South Korean officials had originally pushed to schedule the ceremony for late March so Chinese President Hu Jintao could attend with President Lee Myung-bak while he was in Seoul to participate in the Nuclear Security Summit.

But China gave the idea the cold shoulder.

Difficulty with scheduling or consideration of North Korea may have deterred Hu from attending the ceremony. But many diplomatic observers here view his absence as reflecting Beijing’s unease with Seoul over a series of incidents that have aggravated South Koreans’ sentiment against China.

Public outrage erupted in December over the killing of a South Korean coast guard by a Chinese skipper during a fight for control of a trawler illegally fishing in South Korean waters. South Koreans viewed Beijing’s response as unapologetic.

Seoul officials had wished the ceremony would be held with much more fanfare.

They had envisioned top leaders from South Korea and China attending the launch of a series of events scheduled throughout this year to mark the 20th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between the two countries.

To their disappointment, both sides were represented by vice culture ministers at the ceremony in the National Museum of Korea in Seoul on April 3, which drew little attention from news media here.

According to sources familiar with the matter, South Korean officials had originally pushed to schedule the ceremony for late March so Chinese President Hu Jintao could attend with President Lee Myung-bak while he was in Seoul to participate in the Nuclear Security Summit.

But China gave the idea the cold shoulder.

Difficulty with scheduling or consideration of North Korea may have deterred Hu from attending the ceremony. But many diplomatic observers here view his absence as reflecting Beijing’s unease with Seoul over a series of incidents that have aggravated South Koreans’ sentiment against China.

Public outrage erupted in December over the killing of a South Korean coast guard by a Chinese skipper during a fight for control of a trawler illegally fishing in South Korean waters. South Koreans viewed Beijing’s response as unapologetic.

A local daily ran a photo of the murdered guard’s daughter crying at his funeral, under the headline “Does China see this girl’s tears?”

South Koreans’ antipathy toward their giant neighbor was exacerbated in February over Beijing’s reported moves to repatriate dozens of North Korean defectors captured earlier that month.

Human rights activists and citizens swamped the area outside the Chinese Embassy in Seoul for weeks, urging China not to send the defectors back to the North where they would face harsh punishment. A female lawmaker staged an 11-day hunger protest in front of the embassy before collapsing and being taken to hospital.

Further straining tensions, a Chinese official’s remark laying claim to a submerged reef southwest of South Korea’s southernmost island prompted strong protests from Seoul last month.

Aggravating sentiment

President Lee came forward to express Seoul’s firm stance on these matters, with Chinese Ambassador Zhang Xinsen becoming a familiar sight at the Foreign Ministry.

The atmosphere surrounding the two summits between Lee and Hu this year appeared far from amicable.

Their agreement to start talks on a bilateral free trade deal, which was made during Lee’s visit to Beijing in January, drew little attention from the local media.

Beijing, which sent back a dozen North Korean defectors in late February despite objections from Seoul, balanced the forced repatriation with a measure to allow four of 11 defectors believed to have been staying in South Korean consulates in China for more than two years to go to the South early this month.

Hu suggested the move during his talks with Lee in Seoul last month by pledging efforts to smoothly resolve the defector issue in respect of South Korea’s stance.

Worsening mutual perceptions between the peoples of South Korea and China are mirrored in a series of opinion polls.

According to a survey by a local pollster in December, only 12 percent of South Koreans had a favorable attitude toward China, down from 20 percent in 2005. Those who disliked China increased from 24 percent to 40 percent over the same period.

Respondents who saw relations with China as going well decreased from 51 percent in 2005 to 31 percent last year.

A series of annual surveys by Joongang Ilbo, a vernacular daily, showed China overtaking North Korea and the U.S. in the late 2000s as the country South Koreans disliked the most.

China was cited by 12.5 percent of South Koreans as their most disliked nation in 2008, while 9.7 percent and 9.3 percent selected North Korea and the U.S., respectively. Japan, which put the Korean Peninsula under its colonial rule from 1910-45, was chosen by more than half South Koreans (56.5 percent) as their most disliked country.

Favorable Chinese sentiment toward South Korea declined from 73 on a scale from zero to 100 in 2006 to 53 last year, according to surveys by the East Asia Institute, a Seoul-based think tank.

The uneasy mood appears to have led officials in Seoul and Beijing to designate 2012 as the “year of friendship and exchanges” for their countries.

South Korea and China termed 2002 and 2007, which marked the 10th and 15th anniversary of their formal ties, as years “of exchanges.” Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao attended a 2007 ceremony in Seoul.

“The attachment of friendship to the yearly slogan shows in a paradoxical way that South Korea and China are now in more need of getting closer,” said a retired South Korean diplomat who requested anonymity.

Growth in exchanges

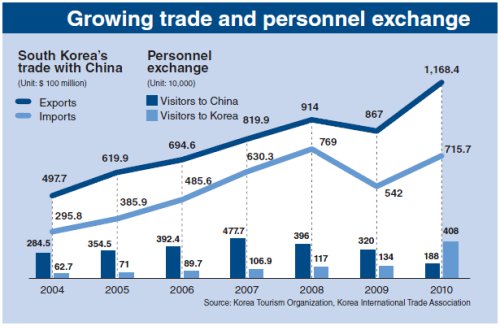

The estranged public sentiment contrasts the rapid growth in trade and personnel exchanges between the two countries over the past two decades.

The volume of bilateral commerce, which stood at $6.4 billion in 1992, ballooned to $213.9 billion last year. China has been the largest trading partner for South Korea since 2004.

The number of South Korean and Chinese visitors to each other’s country also jumped from about 130,000 to more than 6 million over the cited period.

Chinese people have purchased nearly 80 percent of the roughly 45,000 tickets for the Yeosu Expo sold overseas so far, reminding organizers of where they should turn to for more foreign presence at the event in the South Korean port city for three months beginning on May 12.

Officials here say it is not unusual for countries to have more friction in parallel with expanded contact and engagement, and that South Korea and China cannot be expected to be exceptional cases.

“It would be overstated to say South Korea and China have tension just because they have some pending issues,” said Byun Chul-hwan, chief of a division in charge of Chinese affairs at the Foreign Ministry.

“Both sides have continued close consultations,” he said.

Shin Jung-seung, former South Korean ambassador to China, noted it could not be avoided that some disagreements came to the fore between any two countries that have deepened ties and faced conflicting interests in the process.

“What is important is how to settle the discords,” said Shin, who now serves as a chief researcher on China at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy, a training and research institute affiliated with the Foreign Ministry.

The lack of channels between senior leaders from South Korea and China, which functioned efficiently at the initial stage of their relationship, appears to have led to amplifying rather than easing strains on bilateral ties.

Some experts here, however, indicate South Korea may be missing a critical point in dealing with China ― its giant neighbor’s unwavering focus on practical interests.

South Koreans have often expressed anger, frustration or, in some cases, fear about what they see as China’s insensitivity to meeting its moral responsibility and international standards as a rising power rivaling the U.S.

This attitude, however, may arise at least partly from a failure to understand China’s persistent policy of putting top priority on practical matters, the experts note.

Beijing’s decision to set up formal ties with Seoul over Pyongyang’s vehement objection also came from its pragmatic approach toward the two Koreas in the context of reform and openness policy being pushed by its paramount leader Deng Xiaoping since the late 1970s, they say.

As an example of Beijing’s practical approach, they cite a proposal it reportedly made in February that Chinese fishermen captured for illegal fishing in South Korean waters be released in return for sending some North Korean defectors to the South.

In principle, China has said it handles the defector issue in accordance with domestic and international laws and humanitarian considerations, but the reported offer reflects its pursuit of practical interests, the experts argue.

From this point of view, China’s refusal to join international condemnation of North Korea over its torpedo attack on a South Korean naval ship and artillery shelling on an island near the inter-Korean maritime border in 2010 could be easily understood.

Its stance was natural considering the results Beijing could expect from letting its impoverished neighbor, which acts as a buffer zone against South Korea and its allies, be driven to the wall, the experts say.

While it may still help Seoul make its case against Beijing to address international obligations and humanitarian causes, they argue, what is required more to ensure South Korea’s efficient handling of future discords with China would be to secure more bargaining chips and lessen dependence on its giant neighbor.

South Korean officials should depart from their practice of repeatedly asking China to put pressure on North Korea and then being frustrated at its uncooperative stance. Instead they should look for other ways to induce changes in the North, including direct dialogue, the experts say.

Some observers also expect the aggressive approach Russian leader Vladimir Putin is expected to take toward the Korean Peninsula when he returns to the presidency next month may give Seoul new leverage with Beijing.

Franker conversations

Shin called for efforts to strengthen high-level dialogue and improve public perceptions between the two countries.

It is one thing to be on alert on China’s increasing assertiveness and another to exaggerate or have unreasonable fear about its threat, he said.

To boost bilateral ties to match the strategic cooperative partnership agreed on by Lee and Hu in 2008, senior leaders from South Korea and China need to have franker conversations more frequently about their nations’ long-term interests and intentions, he said.

Some officials in Seoul see China may be pushed to the limit of its patience on North Korea when Pyongyang goes ahead with the satellite launch, which South Korea and the U.S. see as a pretext for testing a ballistic missile, later this week or early next week as it announced last month.

They say Pyongyang’s latest provocation may lead Beijing to reconsider its way of calculating its practical interests on the Korean Peninsula.

Shin said there is a chance of Beijing hardening its stance on North Korea, but it is unlikely to push its impoverished ally to a point that risks regime collapse.

He said China could be expected to change its approach toward Korean issues over the long term with the rise of a new generation.

In a survey of 1,000 Chinese college students last year, 40.1 percent said the unification of the two Koreas would be in the best interests of China, compared to 39.4 percent who replied it would be harmful for them.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Hello India] Hyundai Motor vows to boost 'clean mobility' in India](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050672_0.jpg&u=)