Was there a St. Louis woman who could resist Ernest Hemingway?

He married and divorced three of them, prompting Gertrude Stein to quip: “Anyone who’s married three girls from St. Louis hasn’t learned much.”

One might argue it was the “girls” who didn’t learn.

Yet we’ll forgive Hemingway’s first wife, who fell in love when he was only 21.

Handsome and magnetic, Hemingway had little (although some) baggage when he charmed Hadley Richardson in 1920 at a Chicago party.

He’d already been a reporter for the Kansas City Star and recovered from a war injury in Italy. But he was years away from publishing his first novel, “The Sun Also Rises,” which would be dedicated to the red-haired St. Louis woman he wrote letters to several times a week.

Less than a year after they met, Ernest and Hadley left the dreary Midwest for Europe, where they would meet James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Scott Fitzgerald and many others.

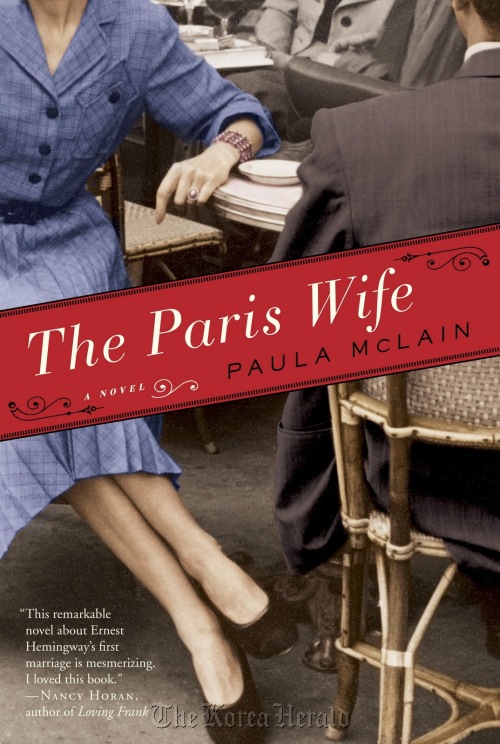

“Of all his wives, Hadley was the one who turned out for the better having known him,” says Paula McLain, author of the novel “The Paris Wife.”

She says it’s almost a “literary biography,” a fictional take on a relationship also documented in letters and books.

Although the marriage of Ernest and Hadley would last only from 1921-27, photos of the young couple picture them clearly in love.

As parents of John (who would beget his own very handsome children, including actresses Mariel and Margaux), the robust Hemingways seemed to beam.

Later, in “A Moveable Feast,” Hemingway remembered Hadley as his truest love: “I wish I had died before I ever loved anyone but her.”

Talking from her home in Cleveland, McLain says that the young, romantic Hemingway will “be a surprise to readers.”

Later in his life, he could seem a caricature of himself, the manly, hard-drinking writer whose work would both inspire and be parodied by generations of writers. He would kill himself in 1961 after electric shock treatments.

But McLain’s story is how Hemingway opens a door for Hadley Richardson, almost eight years his senior and living with her sister’s family.

A home on Cates Avenue is where Richardson cared for her dying mother after studying only one year at Bryn Mawr.

In the novel, Hadley describes her family: “Ours was the quintessentially good family, with Pilgrim lineage on both sides and lots of Victorian manners keeping everything safe and reliable. My father’s father founded the St. Louis Public Library and the Richardson Drug Company, which became the largest pharmaceutical house west of the Mississippi. ... We learned to play piano on a Steinway Grand and spent summers in Ipswich, Massachusetts, at our beach cottage. And everything was very good and fine until it wasn’t.”

Her mother became protective after Hadley, 6, fell out of an upstairs window. Later, her father would lose money in the stock market and kill himself. A sister, Dorothea, died from burns.

When her mother dies, Richardson is 28 and has little to hold her in St. Louis. She also has an inherited income with which to support herself.

Although some critics hint that Hemingway was attracted to her money, McLain doesn’t agree. With Ernest, she says, Hadley has a “wonderful awakening.”

Peggy Shepley, 76, a great-niece of Hadley Richardson, says the couple “were in love, no question.” A St. Louis real estate agent, Shepley says Hadley was a sweet person who cared for her father as a youth after his mother (Dorothea) died.

After moving to Paris, the young Hemingways rented cheap apartments ― one was above a sawmill ― and bought few luxuries. What money they had seemed to be spent on travel. The “Paris wife” witnessed bullfighting in Spain, hiked the Great St. Bernard Pass, skied in Austria and sunbathed on the Riviera.

When Hemingway traveled without her, she waited eagerly for him to return, and she famously lost a bag filled with his early writings while taking a train to meet him.

Gertrude Stein urged them to spend money, like she did, on artists such as Picasso. Hemingway gave Hadley “The Farm” by Joan Miro for a birthday present (it now belongs to the National Gallery of Art).

Hemingway fans know that another well-off woman from St. Louis eventually would betray Hadley ― and become Ernest’s next wife.

Pauline Pfeiffer was the first of three journalists he’d marry, women perhaps more intellectually stimulating, or conniving, than his devoted, piano-playing Hadley.

McLain has no love lost for Pfeiffer, another lovely woman. The Vogue editor comes on the scene in a striking, chipmunk-fur coat.

“I think he was manipulated by Pauline,” McLain says. “I couldn’t sympathize with Pauline because, in a way, she broke up my marriage.”

Among Hemingway fans, gossip about the wives is strong enough that the Pfeiffer farmhouse museum in Arkansas defends Pauline on its website: “While Hemingway biographers, and even Hemingway himself, often cast Pauline as the aggressor in the breakup of their marriage, there is ample evidence that just the opposite was true. Rather than Hemingway being a great catch when they met, he was a struggling, not-yet-famous writer ― and a married man and the father of a son. Pauline was a well-educated, devout Catholic with a great job, a huge trust fund, and countless, more suitable, admirers.”

McLain researched the Hemingway papers at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston (where she happened to meet Zelda Fitzgerald’s biographer, Nancy Milford). But only McLain’s imagination could create the bedroom scene with Pfeiffer that seems to convince Hadley that she can’t stay married.

Hadley’s next marriage lasted almost 40 years, indicating that her divorce from Hemingway may have been even better luck than the marriage.

Her second husband, Paul Mowrer, was a respected journalist and poet, but their life remained out of the spotlight as Hemingway entered it.

Still, McLain says, Hadley was never bitter about her former husband, who gave her all royalties to “The Sun Also Rises.”

And, the author says, “the trauma of his later life reflects back and makes his early life all the more rare and lovely.”

By Jane Henderson

(St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)