The first known COVID-19 death in South Korea was a 63-year-old hospitalized at a closed ward of a psychiatric hospital in Cheongdo, North Gyeongsang Province. The man, who was schizophrenic, died with pneumonia on Feb. 19, 2020, at the hospital where he had been a resident for over 20 years. He tested positive postmortem.

In less than a week after his death, six more at the hospital lost their lives to the virus. All of the 101 patients save for just two ended up getting infected. The outbreak prompted health officials to lock down the entire psych ward, a move that is blamed as a cause for delayed response.

More than 7,500 people in South Korea have officially died with COVID-19 since. What the figures do not tell are countless people who died without ever getting a fighting chance at life, according to families and activists who gathered outside Seoul City Hill on Tuesday morning.

Suh Chae-wan of Lawyers for a Democratic Society, better known by its Korean acronym “Minbyun,” said by locking down the entire ward packed with vulnerable patients, health officials had cut them off from access to timely care.

“Korea’s first coronavirus fatality died in the multibed room among other patients. No efforts were undertaken by public health authorities to save him, or about a hundred others who were left there, exposed to infection,” he said.

“Families are still wondering why they were left to die helplessly, why the government that prides on its pandemic success remains silent on these losses.”

Suh, who is representing families of patients who died at the locked ward, said “no explanation, no acknowledgement, no apology has come from those in charge, including the government.”

“People left behind deserve a public apology.”

Not all pandemic deaths are from the infection.

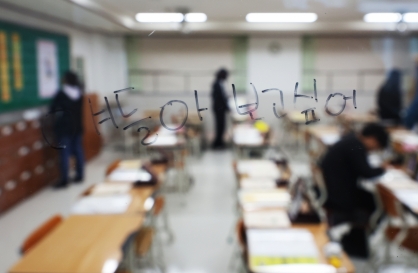

At 17, Jung Yu-yeop died on March 18, 2020 after deteriorating rapidly while staying home for coronavirus-like symptoms. The government protocol at the time prevented him from seeking medical help immediately. Despite a high fever, he had to be tested first before he could be admitted. By the time the test result returned, he was already having trouble breathing.

Although he was negative in 13 of the 14 tests he was given, he was denied visits from family over the six days he was hospitalized. The last his parents saw him was as he was moved to an isolation room in a negative-pressure capsule for carrying infectious patients.

Later, national disease control authorities declared he had not been a COVID-19 case. But he was still deprived of a normal funeral for possible infection concerns.

Speaking at the city plaza, the father, Jung Sung-jae, said two years on he was still waiting for answers to remaining questions surrounding the death of his son. He said he was told by government officials to settle the case through a medical dispute.

“But what had happened to my son should not be brushed off as a personal tragedy,” he said. “From how we view it, it is a case of an absence of government accountability in face of public health crisis.”

In a joint statement human rights activist Ahn Eun-jeong said the victims had been “treated as spread risks, rather than people who deserve dignity and protection.”

“In the final moments control and surveillance took precedence over respect and safety.”

Although death counts are updated daily in government briefings, there was no commemoration. ”Deaths should not be reduced to a number or statistics,” she said.

“Government health officials like to say the case fatality rate here is low, and yet turn a blind eye to the recurring tragedy,” Suh of Minbyun said. “Rather than celebrating the ‘low’ fatality rate what the government ought to do is look back on people whom it had failed to protect, and come up with measures to stop preventable deaths.”

In less than a week after his death, six more at the hospital lost their lives to the virus. All of the 101 patients save for just two ended up getting infected. The outbreak prompted health officials to lock down the entire psych ward, a move that is blamed as a cause for delayed response.

More than 7,500 people in South Korea have officially died with COVID-19 since. What the figures do not tell are countless people who died without ever getting a fighting chance at life, according to families and activists who gathered outside Seoul City Hill on Tuesday morning.

Suh Chae-wan of Lawyers for a Democratic Society, better known by its Korean acronym “Minbyun,” said by locking down the entire ward packed with vulnerable patients, health officials had cut them off from access to timely care.

“Korea’s first coronavirus fatality died in the multibed room among other patients. No efforts were undertaken by public health authorities to save him, or about a hundred others who were left there, exposed to infection,” he said.

“Families are still wondering why they were left to die helplessly, why the government that prides on its pandemic success remains silent on these losses.”

Suh, who is representing families of patients who died at the locked ward, said “no explanation, no acknowledgement, no apology has come from those in charge, including the government.”

“People left behind deserve a public apology.”

Not all pandemic deaths are from the infection.

At 17, Jung Yu-yeop died on March 18, 2020 after deteriorating rapidly while staying home for coronavirus-like symptoms. The government protocol at the time prevented him from seeking medical help immediately. Despite a high fever, he had to be tested first before he could be admitted. By the time the test result returned, he was already having trouble breathing.

Although he was negative in 13 of the 14 tests he was given, he was denied visits from family over the six days he was hospitalized. The last his parents saw him was as he was moved to an isolation room in a negative-pressure capsule for carrying infectious patients.

Later, national disease control authorities declared he had not been a COVID-19 case. But he was still deprived of a normal funeral for possible infection concerns.

Speaking at the city plaza, the father, Jung Sung-jae, said two years on he was still waiting for answers to remaining questions surrounding the death of his son. He said he was told by government officials to settle the case through a medical dispute.

“But what had happened to my son should not be brushed off as a personal tragedy,” he said. “From how we view it, it is a case of an absence of government accountability in face of public health crisis.”

In a joint statement human rights activist Ahn Eun-jeong said the victims had been “treated as spread risks, rather than people who deserve dignity and protection.”

“In the final moments control and surveillance took precedence over respect and safety.”

Although death counts are updated daily in government briefings, there was no commemoration. ”Deaths should not be reduced to a number or statistics,” she said.

“Government health officials like to say the case fatality rate here is low, and yet turn a blind eye to the recurring tragedy,” Suh of Minbyun said. “Rather than celebrating the ‘low’ fatality rate what the government ought to do is look back on people whom it had failed to protect, and come up with measures to stop preventable deaths.”

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)