[Herald Interview] Satrec Initiative poised for leap in Korea’s space rush

By Kim Byung-wookPublished : Sept. 22, 2021 - 15:24

This is the second installment in a series of interviews with executives of Korean companies with space ambitions. -- Ed.

About a month from now, South Korea will launch its first homegrown rocket “Nuri.”

A successful launch of the domestically made space launch vehicle is expected to herald a new space era for the country, where government-led programs transition to market-oriented ventures, with a key hindrance -- the decades-old Korea-US missile guidelines that put curbs on Korea’s space launches -- cleared.

At the vanguard of the Korean space rush is Satrec Initiative.

Founded in 1999 by engineers who built the country’s first satellite Uribyeol 1, the firm manufactures small satellites for Earth observation missions. One of its major clients include the South Korean military, which faces a belligerent and nuclear-armed North Korea.

“To launch a satellite, you have to wait for your turn. If the mission control says, ‘It’s raining’ or ‘There has been a delay,’ you can’t do anything about it,” Jeon Bong-ki, the firm’s managing director, said of the Oct. 21 launch of Nuri.

About a month from now, South Korea will launch its first homegrown rocket “Nuri.”

A successful launch of the domestically made space launch vehicle is expected to herald a new space era for the country, where government-led programs transition to market-oriented ventures, with a key hindrance -- the decades-old Korea-US missile guidelines that put curbs on Korea’s space launches -- cleared.

At the vanguard of the Korean space rush is Satrec Initiative.

Founded in 1999 by engineers who built the country’s first satellite Uribyeol 1, the firm manufactures small satellites for Earth observation missions. One of its major clients include the South Korean military, which faces a belligerent and nuclear-armed North Korea.

“To launch a satellite, you have to wait for your turn. If the mission control says, ‘It’s raining’ or ‘There has been a delay,’ you can’t do anything about it,” Jeon Bong-ki, the firm’s managing director, said of the Oct. 21 launch of Nuri.

“The key is to launch a satellite at the right time and get the information you need at the right moment. This is why we need a homegrown rocket, even if it’s more expensive than SpaceX.”

The local satellite industry had long been shackled by complex geopolitical situations surrounding the Korean Peninsula, epitomized by the now-defunct US curbs on S. Korea’s missile development. But Satrec believes it was the perfect environment that enabled them to make rapid advances in the global private satellite market.

“The Korean Peninsula is the world’s most sensitive region. The South Korean military tells us, ‘If you can prove it here, you’ll have no problem elsewhere.’ Providing successful detection and analysis services in the peninsula warrants our technology overseas,” Jeon said.

As of September 2020, about 65 percent of the firm’s satellite sales came from exports to the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Singapore, Malaysia, among others.

Utilizing the Korean Peninsula as its giant test bed, Satrec Initiative has evolved into the nation’s sole private company equipped with a complete satellite value chain. From manufacturing the satellite body, satellite camera and ground station to analyzing and selling satellite footage, the company offers the whole package.

Yet, there exists an overwhelming technological gap between Satrec and established players in the US and Europe. Asked what its survival strategy is, Jeon pointed to the firm’s greatest weapon -- price competitiveness.

“Satrec Initiative’s small satellites can deliver 80 percent performance at 20 percent the price,” Jeon said.

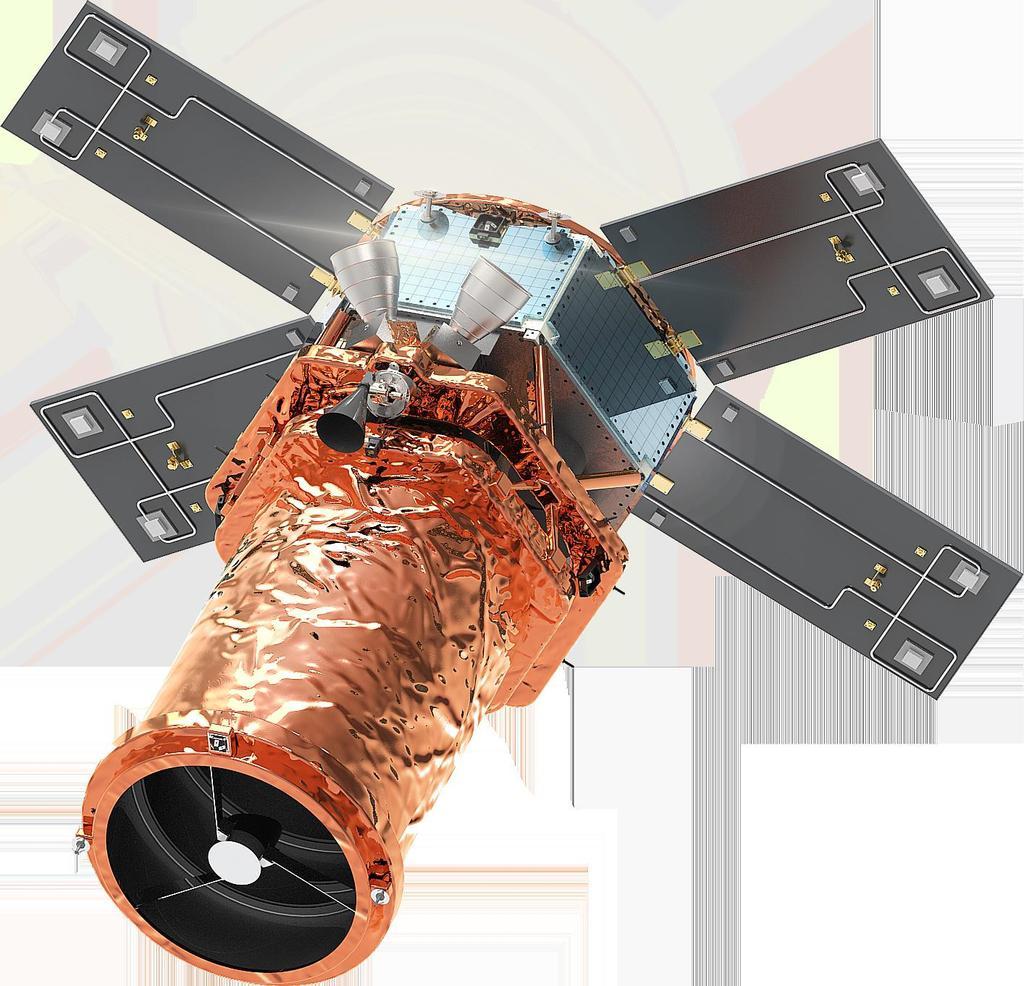

According to Jeon, when Satrec Initiative launched its small-sized SpaceEye-X observation satellite, it immediately emerged as an alternative to the large-sized WorldView-3 satellite in the market.

WorldView-3 offered a resolution of 0.31 meter, clear enough to identify the types of vehicles on the ground, but it was heavy and expensive, weighing 2,800 kilograms and costing $300 million. SpaceEye-X, though offering a less accurate resolution of 0.45 meter, only weighed 400 kilograms and cost $60 million.

“Over the last 20 years, all we thought about was optimization. Look at Hyundai Motor. The carmaker knows how to source parts from different vendors, assemble them in an optimized design and sell the car at the price it wants. Satellite business is pretty much the same,” Jeon said.

“Inside a satellite body, there are different parts controlling heat, electricity, power and so on. The know-how is to stuff them inside without any interference.”

South Korea’s comparatively low labor costs also enabled them to cut prices, Jeon added.

Based on decades of optimization skills, Satrec Initiative is pushing the limits of small satellites, currently developing SpaceEye-T, a small satellite with a resolution of 0.3 meter, the same specs as WorldView-3. The price of SpaceEye-T is $100 million, one-third of WorldView-3.

The project could take shape thanks to the investment from Hanwha Aerospace, which acquired a 30 percent stake in Satrec Initiative at 108.9 billion won ($92 million).

According to Jeon, Hanwha’s investment will not just aid Satrec. The money will trickle down to smaller players in the local field, revitalizing domestic supply chains for satellites.

When the government -- the state-run Korea Aerospace Research Institute to be more precise -- was the only source of cash inflows, rules of economics and business potential were often overshadowed by policy goals. The KARI used its budget to localize several satellite components, which it deemed strategically important, but their mass production or local supply chains were not of their main concern.

To lead and further advance Korea’s satellite industry, Satrec Initiative is set to expand its business frontiers, employing artificial intelligence for satellite image analysis and exploring commercial-off-the-shelves, or COTS parts, for its satellites.

“In the past, the industry was very conservative and only used parts that had been verified in space no matter how old they were. But recently, startups are using commercial parts as satellite parts. When we saw those satellites performing well in space, it kind of changed our thoughts. For instance, some startups are using DSLR image sensors for satellite cameras,” Jeon said.

The local satellite industry had long been shackled by complex geopolitical situations surrounding the Korean Peninsula, epitomized by the now-defunct US curbs on S. Korea’s missile development. But Satrec believes it was the perfect environment that enabled them to make rapid advances in the global private satellite market.

“The Korean Peninsula is the world’s most sensitive region. The South Korean military tells us, ‘If you can prove it here, you’ll have no problem elsewhere.’ Providing successful detection and analysis services in the peninsula warrants our technology overseas,” Jeon said.

As of September 2020, about 65 percent of the firm’s satellite sales came from exports to the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Singapore, Malaysia, among others.

Utilizing the Korean Peninsula as its giant test bed, Satrec Initiative has evolved into the nation’s sole private company equipped with a complete satellite value chain. From manufacturing the satellite body, satellite camera and ground station to analyzing and selling satellite footage, the company offers the whole package.

Yet, there exists an overwhelming technological gap between Satrec and established players in the US and Europe. Asked what its survival strategy is, Jeon pointed to the firm’s greatest weapon -- price competitiveness.

“Satrec Initiative’s small satellites can deliver 80 percent performance at 20 percent the price,” Jeon said.

According to Jeon, when Satrec Initiative launched its small-sized SpaceEye-X observation satellite, it immediately emerged as an alternative to the large-sized WorldView-3 satellite in the market.

WorldView-3 offered a resolution of 0.31 meter, clear enough to identify the types of vehicles on the ground, but it was heavy and expensive, weighing 2,800 kilograms and costing $300 million. SpaceEye-X, though offering a less accurate resolution of 0.45 meter, only weighed 400 kilograms and cost $60 million.

“Over the last 20 years, all we thought about was optimization. Look at Hyundai Motor. The carmaker knows how to source parts from different vendors, assemble them in an optimized design and sell the car at the price it wants. Satellite business is pretty much the same,” Jeon said.

“Inside a satellite body, there are different parts controlling heat, electricity, power and so on. The know-how is to stuff them inside without any interference.”

South Korea’s comparatively low labor costs also enabled them to cut prices, Jeon added.

Based on decades of optimization skills, Satrec Initiative is pushing the limits of small satellites, currently developing SpaceEye-T, a small satellite with a resolution of 0.3 meter, the same specs as WorldView-3. The price of SpaceEye-T is $100 million, one-third of WorldView-3.

The project could take shape thanks to the investment from Hanwha Aerospace, which acquired a 30 percent stake in Satrec Initiative at 108.9 billion won ($92 million).

According to Jeon, Hanwha’s investment will not just aid Satrec. The money will trickle down to smaller players in the local field, revitalizing domestic supply chains for satellites.

When the government -- the state-run Korea Aerospace Research Institute to be more precise -- was the only source of cash inflows, rules of economics and business potential were often overshadowed by policy goals. The KARI used its budget to localize several satellite components, which it deemed strategically important, but their mass production or local supply chains were not of their main concern.

To lead and further advance Korea’s satellite industry, Satrec Initiative is set to expand its business frontiers, employing artificial intelligence for satellite image analysis and exploring commercial-off-the-shelves, or COTS parts, for its satellites.

“In the past, the industry was very conservative and only used parts that had been verified in space no matter how old they were. But recently, startups are using commercial parts as satellite parts. When we saw those satellites performing well in space, it kind of changed our thoughts. For instance, some startups are using DSLR image sensors for satellite cameras,” Jeon said.

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)