[Life, unprepared] Pension reality check looms as reformists face public backlash

Political opponents, experts urge government to reveal ‘hidden’ numbers in pension balance sheet, saying younger Koreans may end up paying more for less benefits

By Son Ji-hyoungPublished : Aug. 2, 2021 - 17:26

This is the final installment of a series of articles investigating financial activities of seniors amid the rapid digitalization of the finance industry. -- Ed.

The birth of the National Pension Service in 1988 epitomized South Korea’s ambition to achieve economic maturity, to build a socioeconomic safety net and to materialize hardworking people’s dreams for a stable and quality life after retirement.

More than three decades on, the mandatory social security pension scheme has risen to be the third-largest pension fund in the world, providing retirees with earnings-related cash income in Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

But the scheme is now being met with daunting challenges, as the imbalance between contributions and benefits persists despite having undergone two pension reforms, in 1998 and 2007.

Korea’s pension scheme covering general employees is designed to offer benefits of more than double the contributions as people retire, according to the National Pension Institute in 2019.

The scheme, now perceived as the last bastion of economic independence of seniors in Korea, however, is falling short of keeping up with a faster-than-expected demographic shift. This is despite the 2007 reform that incrementally decreases the benefits level from 50 percent to 40 percent by 2028, while maintaining the contribution level at 9 percent.

Political circles, while acknowledging the problem, have still often found themselves in a deadlock in terms of initiating talks for pension reform.

Public backlash has ensued in previous reforms, out of disappointment that succeeding generations in Korea would be forced to share the financial burden of the pension fund by benefitting less than the prior generation.

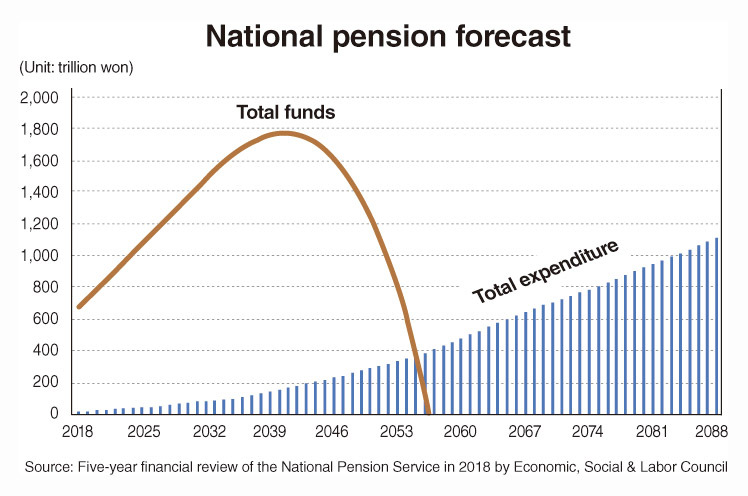

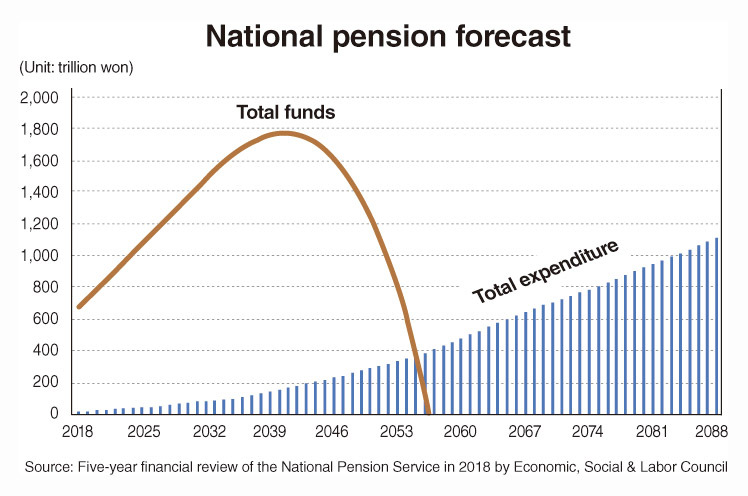

Korean presidents, including the incumbent Moon Jae-in, have thrown cold water over the agenda to slow down the depletion of what could be worth as much as 1,778 trillion won ($1.55 trillion) by 2043.

W2,000tr gone in 15 years

Ahead of the presidential election next year, some presidential hopefuls are reigniting calls to resume stalled reform talks, doubling down on criticisms against the Moon administration for a lack of willingness to slow down the pace of depletion and tackle inadequate funding policies.

One of the latest to do so is Yoo Seong-min, a former four-term conservative lawmaker who launched his presidential bid in May, along with rival Yun Hee-suk, who expressed a bid Sunday to carry out an occupational pension overhaul.

Opening public discourse on improving the pension’s financial health is intended to highlight “hidden” numbers in the pension fund’s balance sheet, Yoo said.

“Important facts regarding the public pension scheme still remain hidden,” Yoo told The Korea Herald by email.

“Unsettling facts will eventually ignite a productive discussion surrounding the pension reform, urging people concerned about the future of Korea to sympathize with the imminent and inevitable need for reform.”

“We have been slow to advance pension reform talks despite little chance of being sustainable, because the public was not able to take notice of the pension fund’s unfunded liabilities,” Yoo said.

The government has argued it has yet to report the NPS’ unfunded liabilities by abiding by a standard suggested by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Without any measure to curb the growth of the implicit obligations, however, reformists in academic circles say the pace of depletion will accelerate as the fund draws to the end of its life cycle.

According to the five-year regular financial review of the NPS in 2018, the entire fund plus additional contributions and investment returns will be gone by 2056.

“What’s alarming is, over 2,000 trillion won worth of funds is projected to be exhausted within 15 years,” said Yun Suk-myung, president of the Korean Pension Association, adding the accumulated deficit of the national pension will stand at a whopping 17,000 trillion won by 2088.

Once the fund is depleted, contributors will subsequently face a sharp hike in their contribution rate to make up for obligations in the underfunded scheme.

Without any further reform, employers and employees are estimated to pay matching contributions of some 30 percent, a substantial hike compared to the current contribution level of 9 percent, posing financial threats to both individuals and businesses.

“The NPS is capable of distributing benefits to pensioners as promised, only on the condition that contributions by the future generation are much greater than the current level,” said Yang Joon-mo, an economics professor at Yonsei University. “It’s unfair to future generations.”

Hot potato

These factors add up to a bleak outlook for the pension system’s sustainability.

Korea is widely forecast to become a superaged society in 2025, in which the proportion of those aged 65 and older will exceed 20 percent of the total population. The country has been an aged society since 2017, as the proportion of such people topped 14 percent.

The fertility rate in Korea has fallen sharply in the past couple of years. The number of expected babies per South Korean woman fell to 0.84 in 2020, from the previous record low of 0.92 in 2019.

This makes the pension fund depletion scenario as of 2018 look rather rosy, as the projection is based on a fertility rate fixed at 1.05 from 2016 to 2088.

In this regard, pensioners are projected to outnumber contributors within a few decades, amid a rapid demographic shift in the country where the population has been in decline since 2019. Government data shows the number of pensioners will rise threefold to 17.2 million over the next 40 years by 2060, while the working-age population will shrink by nearly half to 12.9 million during the same period.

The NPS, the operator of the pension fund, agrees on growing calls for pension reform, but its spokesman said the ball is in the court of the National Assembly because any change in a pension scheme must involve a revision of the National Pension Act. Pension reform is out of its reach with the NPS being designed to carry out national pension operations commissioned under the same rule, he said.

It is the Welfare Ministry that administers the pension business, he went on, stressing the pension control tower, not the NPS, is working on a new five-year financial review of the pension by 2023 to reflect the faster-than-expected fertility rate decline and other factors.

The birth of the National Pension Service in 1988 epitomized South Korea’s ambition to achieve economic maturity, to build a socioeconomic safety net and to materialize hardworking people’s dreams for a stable and quality life after retirement.

More than three decades on, the mandatory social security pension scheme has risen to be the third-largest pension fund in the world, providing retirees with earnings-related cash income in Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

But the scheme is now being met with daunting challenges, as the imbalance between contributions and benefits persists despite having undergone two pension reforms, in 1998 and 2007.

Korea’s pension scheme covering general employees is designed to offer benefits of more than double the contributions as people retire, according to the National Pension Institute in 2019.

The scheme, now perceived as the last bastion of economic independence of seniors in Korea, however, is falling short of keeping up with a faster-than-expected demographic shift. This is despite the 2007 reform that incrementally decreases the benefits level from 50 percent to 40 percent by 2028, while maintaining the contribution level at 9 percent.

Political circles, while acknowledging the problem, have still often found themselves in a deadlock in terms of initiating talks for pension reform.

Public backlash has ensued in previous reforms, out of disappointment that succeeding generations in Korea would be forced to share the financial burden of the pension fund by benefitting less than the prior generation.

Korean presidents, including the incumbent Moon Jae-in, have thrown cold water over the agenda to slow down the depletion of what could be worth as much as 1,778 trillion won ($1.55 trillion) by 2043.

W2,000tr gone in 15 years

Ahead of the presidential election next year, some presidential hopefuls are reigniting calls to resume stalled reform talks, doubling down on criticisms against the Moon administration for a lack of willingness to slow down the pace of depletion and tackle inadequate funding policies.

One of the latest to do so is Yoo Seong-min, a former four-term conservative lawmaker who launched his presidential bid in May, along with rival Yun Hee-suk, who expressed a bid Sunday to carry out an occupational pension overhaul.

Opening public discourse on improving the pension’s financial health is intended to highlight “hidden” numbers in the pension fund’s balance sheet, Yoo said.

“Important facts regarding the public pension scheme still remain hidden,” Yoo told The Korea Herald by email.

“Unsettling facts will eventually ignite a productive discussion surrounding the pension reform, urging people concerned about the future of Korea to sympathize with the imminent and inevitable need for reform.”

“We have been slow to advance pension reform talks despite little chance of being sustainable, because the public was not able to take notice of the pension fund’s unfunded liabilities,” Yoo said.

The government has argued it has yet to report the NPS’ unfunded liabilities by abiding by a standard suggested by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Without any measure to curb the growth of the implicit obligations, however, reformists in academic circles say the pace of depletion will accelerate as the fund draws to the end of its life cycle.

According to the five-year regular financial review of the NPS in 2018, the entire fund plus additional contributions and investment returns will be gone by 2056.

“What’s alarming is, over 2,000 trillion won worth of funds is projected to be exhausted within 15 years,” said Yun Suk-myung, president of the Korean Pension Association, adding the accumulated deficit of the national pension will stand at a whopping 17,000 trillion won by 2088.

Once the fund is depleted, contributors will subsequently face a sharp hike in their contribution rate to make up for obligations in the underfunded scheme.

Without any further reform, employers and employees are estimated to pay matching contributions of some 30 percent, a substantial hike compared to the current contribution level of 9 percent, posing financial threats to both individuals and businesses.

“The NPS is capable of distributing benefits to pensioners as promised, only on the condition that contributions by the future generation are much greater than the current level,” said Yang Joon-mo, an economics professor at Yonsei University. “It’s unfair to future generations.”

Hot potato

These factors add up to a bleak outlook for the pension system’s sustainability.

Korea is widely forecast to become a superaged society in 2025, in which the proportion of those aged 65 and older will exceed 20 percent of the total population. The country has been an aged society since 2017, as the proportion of such people topped 14 percent.

The fertility rate in Korea has fallen sharply in the past couple of years. The number of expected babies per South Korean woman fell to 0.84 in 2020, from the previous record low of 0.92 in 2019.

This makes the pension fund depletion scenario as of 2018 look rather rosy, as the projection is based on a fertility rate fixed at 1.05 from 2016 to 2088.

In this regard, pensioners are projected to outnumber contributors within a few decades, amid a rapid demographic shift in the country where the population has been in decline since 2019. Government data shows the number of pensioners will rise threefold to 17.2 million over the next 40 years by 2060, while the working-age population will shrink by nearly half to 12.9 million during the same period.

The NPS, the operator of the pension fund, agrees on growing calls for pension reform, but its spokesman said the ball is in the court of the National Assembly because any change in a pension scheme must involve a revision of the National Pension Act. Pension reform is out of its reach with the NPS being designed to carry out national pension operations commissioned under the same rule, he said.

It is the Welfare Ministry that administers the pension business, he went on, stressing the pension control tower, not the NPS, is working on a new five-year financial review of the pension by 2023 to reflect the faster-than-expected fertility rate decline and other factors.

Experts agree that what is challenging in much-needed reform talks is to have employees and employers engaged, as they are already likely fatigued by previous pension reforms as well as lingering COVID-19 stress and sagging economic growth.

“The pension scheme was born against the background of a growing population and high interest rate. ... With no one taking the responsibility, an acute rise in financial burden for the older population will become inevitable,” said Yang of Yonsei University.

“In the wake of the low-interest environment, pension schemes will have no choice but to rely more on contributions. But this will weigh on contributors’ financial burden of employers and employees, in addition to their existing burden of tax payment and mandatory health insurance.”

Yun of the Korean Pension Association insisted that a labor market reform be executed in line with the pension reform, given that Koreans pay contributions to the pension scheme for less than 30 years on average, especially as those 60 or older are pushed out of the job market and often turn to part-time jobs to eke out a living.

“A labor market reform must come along with a pension reform to reflect changing demographics in the pension scheme redesign,” Yun said. “How can a country survive with its people working for an average of 27 years in the world of a 100-year life span?”

“The pension scheme was born against the background of a growing population and high interest rate. ... With no one taking the responsibility, an acute rise in financial burden for the older population will become inevitable,” said Yang of Yonsei University.

“In the wake of the low-interest environment, pension schemes will have no choice but to rely more on contributions. But this will weigh on contributors’ financial burden of employers and employees, in addition to their existing burden of tax payment and mandatory health insurance.”

Yun of the Korean Pension Association insisted that a labor market reform be executed in line with the pension reform, given that Koreans pay contributions to the pension scheme for less than 30 years on average, especially as those 60 or older are pushed out of the job market and often turn to part-time jobs to eke out a living.

“A labor market reform must come along with a pension reform to reflect changing demographics in the pension scheme redesign,” Yun said. “How can a country survive with its people working for an average of 27 years in the world of a 100-year life span?”

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)