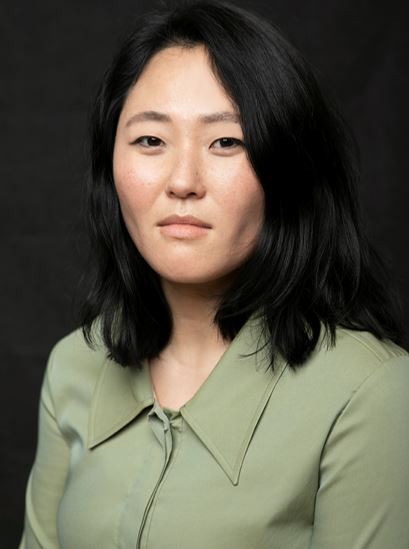

[Herald Interview] Adoptee filmmaker shocked by reality of Korea's single moms

By Song Seung-hyunPublished : June 6, 2021 - 15:29

For filmmaker Sun Hee Engelstoft, who was born in South Korea in 1982 and sent to Denmark for adoption when she was 4 months old, it was shocking to witness the reality facing unmarried mothers in Korea.

“In the West and where I grew up in Denmark, there is this idea that all Korean women just easily give away their children because there are so many adoptees,” Engelstoft said during an interview with The Korea Herald.

Korea has sent more than 200,000 children abroad since the 1950-53 Korean War.

In the process of creating a documentary film, Engelstoft visited the Aesuhwon shelter for single mothers on Jeju Island and came to see that the decision to give a child away is not made solely by the child’s mother.

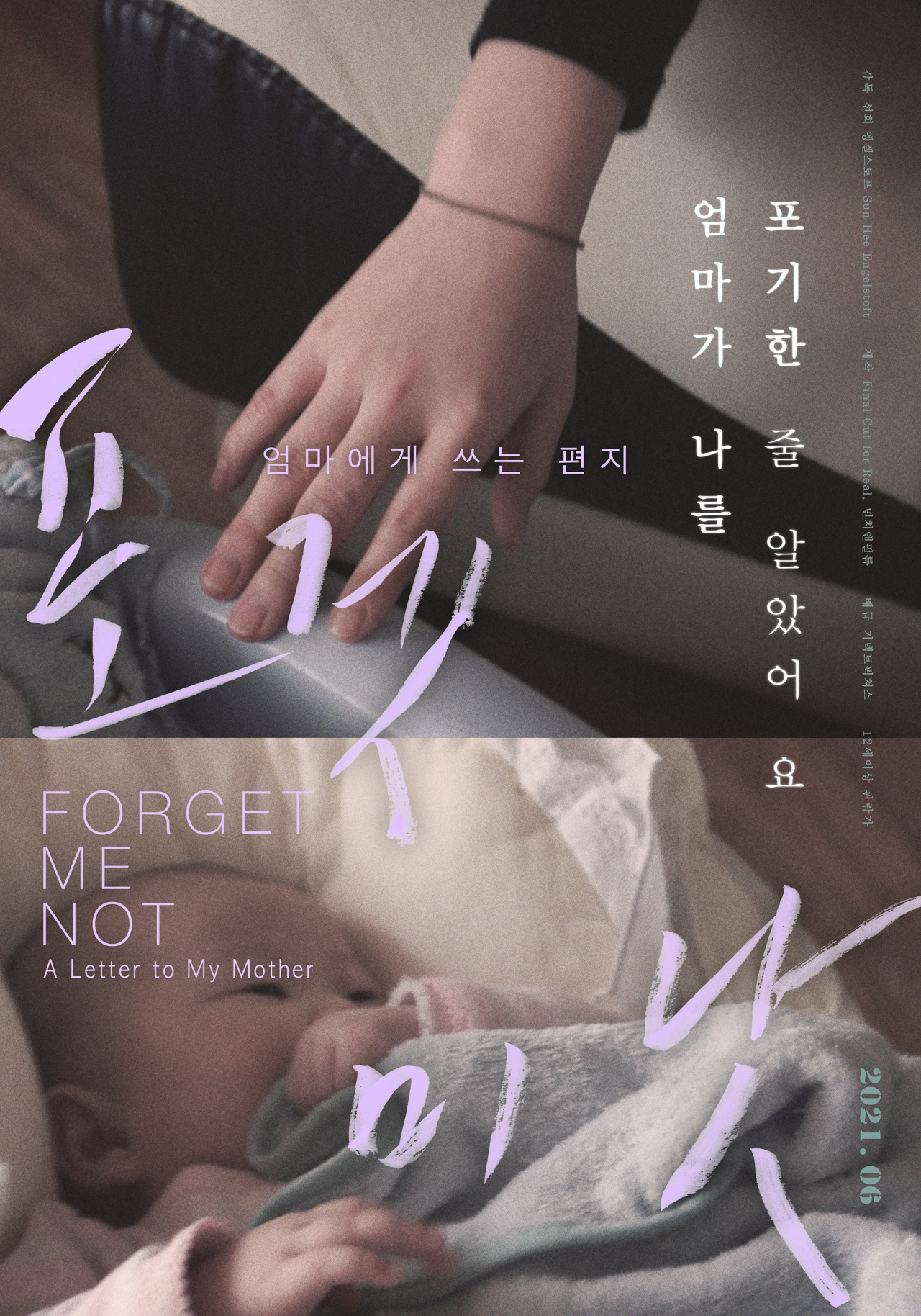

Her film, “Forget Me Not -- A Letter to My Mother,” shows how Korean single moms are pressured into giving their babies up for adoption even if they don’t want to.

Engelstoft spent nearly two years at the shelter on Jeju to show the reality facing unmarried mothers in Korea.

“I had like 350 hours of footage,” Engelstoft said.

Engelstoft decided to make the film after visiting a shelter for single mothers during the International Korean Adoptee Association’s gathering in 2004.

“I went on a motherland tour that was organized by the Overseas Korean Foundation. We went to try hanbok, kimchi factory and papermaking. The last stop on the tour was a shelter that was run by Catholic nuns,” she said. “When I was about to leave, there was a woman who came to me personally. She was eight months pregnant and she just looked at me and asked me, ‘Are you happy to be adopted?’ I didn’t know what to answer her. I could see her desperation that she really wanted to know if I was happy,” she said.

Engelstoft also shared her bitter first experience of looking for her birth mother in Korea.

In 2002, when she turned 20, she came back to Korea for the first time with her adoptive parents. During the visit they went to Holt International, the agency that arranged Engelstoft’s adoption, and were told to visit the orphanage in Busan that had her adoption records.

According to the orphanage’s director, a woman who had the same name as Engelstoft’s birth mother acknowledged that she had once given a child up for adoption, she said. But the director said the woman rejected an offer to meet Engelstoft, saying she had her own family.

“Everything was completely new to me. And all of a sudden I start looking for my mother and the first thing I get is rejection so I was heartbroken,” she said.

The filmmaker added that she doubted the credibility of the information that she got from the director of the orphanage in Busan.

“When we were about to leave, he told my adoptive parents that if we could make a donation, then perhaps he could give us more information. But we never donated. So I didn’t get new information. But I always kind of questioned the accuracy of the information that he gave me because he asked for money,” she said. “It was very uncomfortable for me and also for my adoptive parents.”

During the interview, she also raised questions about the transparency of the international adoption system in Korea.

“If you want to buy a child (from Korea) in Denmark, it cost $50,000, today. And I am just wondering where does that money go to,” she said. “What is sort of the trend internationally in countries like the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland is that they have investigative committees appointed by the government to find out how the agency and the system are working,” she said.

Engelstoft also said the shelters that international adoption agencies run cannot provide the help that unmarried mothers need.

“In the West and where I grew up in Denmark, there is this idea that all Korean women just easily give away their children because there are so many adoptees,” Engelstoft said during an interview with The Korea Herald.

Korea has sent more than 200,000 children abroad since the 1950-53 Korean War.

In the process of creating a documentary film, Engelstoft visited the Aesuhwon shelter for single mothers on Jeju Island and came to see that the decision to give a child away is not made solely by the child’s mother.

Her film, “Forget Me Not -- A Letter to My Mother,” shows how Korean single moms are pressured into giving their babies up for adoption even if they don’t want to.

Engelstoft spent nearly two years at the shelter on Jeju to show the reality facing unmarried mothers in Korea.

“I had like 350 hours of footage,” Engelstoft said.

Engelstoft decided to make the film after visiting a shelter for single mothers during the International Korean Adoptee Association’s gathering in 2004.

“I went on a motherland tour that was organized by the Overseas Korean Foundation. We went to try hanbok, kimchi factory and papermaking. The last stop on the tour was a shelter that was run by Catholic nuns,” she said. “When I was about to leave, there was a woman who came to me personally. She was eight months pregnant and she just looked at me and asked me, ‘Are you happy to be adopted?’ I didn’t know what to answer her. I could see her desperation that she really wanted to know if I was happy,” she said.

Engelstoft also shared her bitter first experience of looking for her birth mother in Korea.

In 2002, when she turned 20, she came back to Korea for the first time with her adoptive parents. During the visit they went to Holt International, the agency that arranged Engelstoft’s adoption, and were told to visit the orphanage in Busan that had her adoption records.

According to the orphanage’s director, a woman who had the same name as Engelstoft’s birth mother acknowledged that she had once given a child up for adoption, she said. But the director said the woman rejected an offer to meet Engelstoft, saying she had her own family.

“Everything was completely new to me. And all of a sudden I start looking for my mother and the first thing I get is rejection so I was heartbroken,” she said.

The filmmaker added that she doubted the credibility of the information that she got from the director of the orphanage in Busan.

“When we were about to leave, he told my adoptive parents that if we could make a donation, then perhaps he could give us more information. But we never donated. So I didn’t get new information. But I always kind of questioned the accuracy of the information that he gave me because he asked for money,” she said. “It was very uncomfortable for me and also for my adoptive parents.”

During the interview, she also raised questions about the transparency of the international adoption system in Korea.

“If you want to buy a child (from Korea) in Denmark, it cost $50,000, today. And I am just wondering where does that money go to,” she said. “What is sort of the trend internationally in countries like the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland is that they have investigative committees appointed by the government to find out how the agency and the system are working,” she said.

Engelstoft also said the shelters that international adoption agencies run cannot provide the help that unmarried mothers need.

“At the agency-run shelters, the first question they ask is, ‘Are you willing to give away the baby?’” she said.

Only women who agree to give their babies away can stay at the shelter, she said.

Toward the end of the interview, she was asked what she would say if she could write a letter to her birth mother.

“(The core message that I want to tell her is) that I love her. I think everything else becomes less important. Besides that, I hope that she has the courage to meet me,” she said. “I listened to so many other women’s stories but I haven’t heard hers. I would like to really listen to what happened to her.”

“Forget Me Not -- A Letter to My Mother” is now in local theaters. The film will not be distributed through online streaming platforms at the request of the women at the Aesuhwon shelter, according to film distributor Connect Pictures.

By Song Seung-hyun (ssh@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)