[Weekender] Is she real? Artificial humans move to the fore

With Miquela, Imma, Sua, Vincent and now Samsung’s Neon, the CGI demographic grows

By Lim Jeong-yeoPublished : July 11, 2020 - 16:01

If the names Miquela or Imma ring a bell, you have been keeping up with the growing demographic of digital humans.

Miquela and Imma are Instagram influencers, respectively followed by 2.48 million and 200,000 users.

They are computer-generated imageries, but have pretty realistic personal descriptions.

For example, Miquela is an American that hails from Los Angeles, California, who has Spanish and Brazilian heritage. Her passions are music and creating a world where women‘s voices are heard.

“If she was real, you would want to be her friend,” fans comment under Miquela’s YouTube videos. “I realize she could live for centuries,” reads another thought-provoking line in the thread.

Miquela was created in 2016 by tech company Brud’s co-founders Sara DeCou and Trevor McFedries. And while some say her existence is almost like a chilling episode of “Black Mirror,” Miquela was named among Time’s Most Influential People on the Internet in 2018.

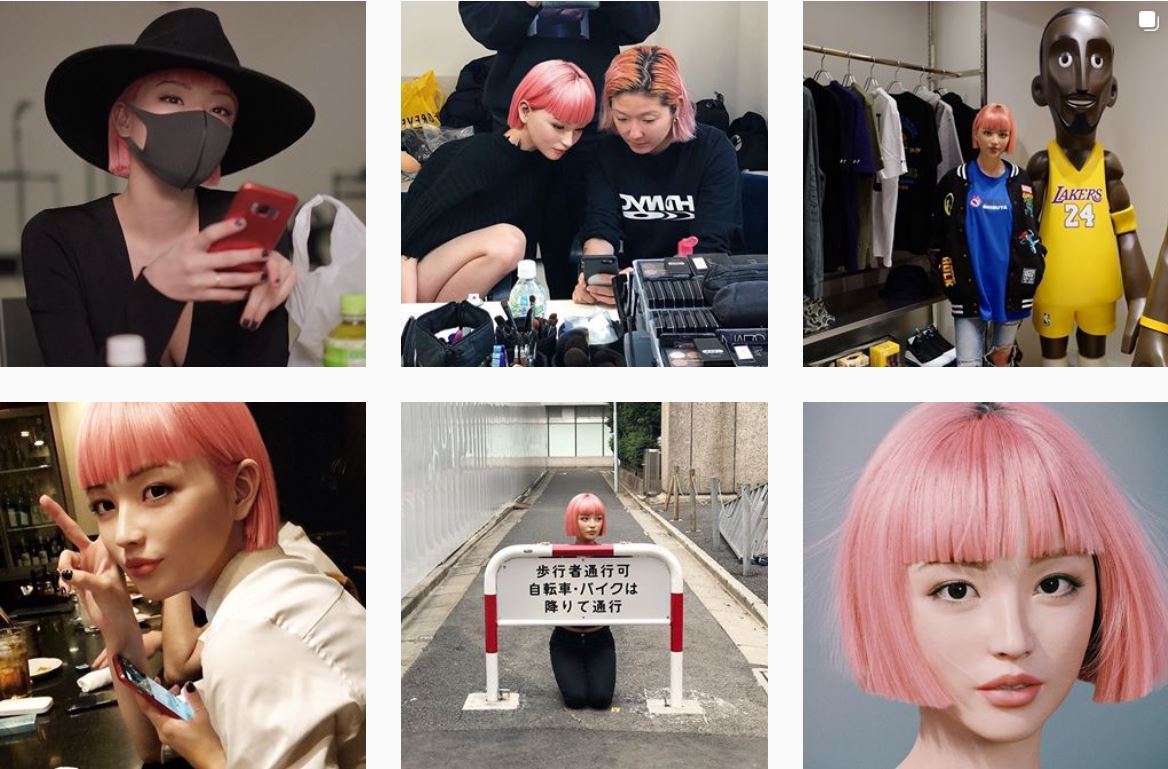

On the other side of the globe there’s Imma, a Japanese Instagram star.

The pink-haired Asian beauty has flawless features that are only matched by her singular sense of fashion.

Imma could be a TV celebrity -- if only she were a real person.

“I’m a virtual girl. I’m interested in Japanese culture, film and art,” reads her profile on Instagram.

But how does she look and feel so real? Imma‘s Instagram photos show her in hip Tokyo neighborhoods such as Akihabara wearing this season’s looks from high-fashion houses. She even posed next to real human models for the cover of a Japanese fashion magazine and starred in a commercial for cosmetic brand SK II’s Pitera Essence skin care.

The trick is that Imma’s face is computer-generated on to a real person’s body, allowing her to blend in seamlessly with the landscape and other people.

Digital humans in Korea

The history of virtual humans for Korea dates back to the 1990s, when Korean “cyber singer” Adam debuted in 1998. Modeled after actor Won Bin, Adam immediately drew attention here despite his still rudimentary and slightly jarring dance moves.

Adam raked in 500 million won (about $420,000 now) in the first three months he was active, selling over 200,000 albums and pulling off gigs as a commercial model.

Fast-forward to 2020, Korea now has Sua, a real-time computer graphic model created by two-man developer studio Sua Digital.

Sua is the face of the Unity Technologies Korea, maker of the game development engine Unity, with which Sua was built.

At first glance, Sua resembles a K-pop star, but one can never place a thumb on exactly who she looks like.

“In making Sua, we paid close attention to her features so that she is endearing but at the same time unique on her own,” said Kim Hyung-il, CEO of Sua Digital in an interview with The Korea Herald.

“Our priority was for Sua to go over the uncanny valley, and it’s rewarding to receive positive feedback from the public,” Kim said.

The “uncanny valley” is a psychological concept of unease or revulsion people can feel toward artificial intelligence or humanoids. Generally, people become more empathetic to unreal objects as they appear more humanlike. But at the point where a humanoid appears very similar, yet clearly not human, they grow cold and unsettled toward it. The creation can theoretically overcome the uncanny valley with the perfection of its look, and people will feel welcoming toward it.

“Digital humans stand out in that they are not limited by physics of time and space. They carry out commands as they are given, and can be adapted to various visual effects,” Kim said, “In broad terms, digital humans can be applied to all sorts of activities that happen in screens.”

Sua was made using real-time rendering technology, which is a cutting-edge visual effect that enables quicker production time, lower production cost and minimal workload when adapting to different scenarios after the first character development.

Sua could be an actor, entertainer, host, game character or broadcaster, said Kim, adding that his team is contemplating the best career path for Sua.

“As you can see, Sua has the Korean look. We are proud that global enterprises are showing interest in hiring Sua,” Kim said.

Evolution of artificial humans

With the coronavirus pandemic, noncontact has become a buzzword in business. Interest in digital humans is growing, Kim said, but this doesn’t mean CGI humans will ever eclipse real people.

“Making the digital human, commanding tasks and carrying out their maintenance is all humans’ doing,” Kim said, “All matters have two sides. If graphics replace humans at work, there will inevitably arise new jobs for humans to operate these digital characters,” said Kim.

And for those who feel uncomfortable that these digital humans tend to be female, meet Vincent, a digital human by tech company GiantStep, and the Neons by Samsung Research America’s Star Labs.

Vincent is a real-time rendering digital avatar of GiantStep’s developer, Vincent Lorant.

Digital humans have existed before, notably in Hollywood films. But those required six to 12 months of production time and came at astronomical costs. The characters could not be interacted with, meaning they could not be applied to other industries.

However, the use of a real-time engine for game development led to the leap to entertainment content, allowing for more interactive and immersive AI digital humans.

Vincent was made using the Unreal Engine by Epic Games.

“Seeing Vincent, we are getting requests to build digital celebrity, digital concierge, game characters and app service,” said Shin Won-ho, director and head of the new media business division at GiantStep.

“In near future, there will be a new industry for digital entertainers, and digital humans will find roles as faces to AI insurance planners and call center communicators.” Shin said.

Similarly, Samsung Research Lab’s Star Labs plans to build its Neon humans as next-generation workers who could be AI personal shoppers and foreign language instructors.

Neons will have memories and feelings that enable them to pick up the work from where they left it. The Neon project is headed by Pranav Mistry, the CEO of Star Labs.

But why?

The question remains: Why do humans create other human-looking things? Why should artificial intelligence take on the form of a biped, with an inviting smile and a helpful tone of voice?

Confronted with bizarrely realistic computer graphics-generated digital humans, don’t we end up questioning our own humanity?

“The process of socialization is of mirroring. Humans observe and imitate others – when we are young, we copy those close to us and as we grow we begin to mimic conceptual beings. Mirroring is the fundamental mechanism of all human relationship,” said Lee Taek-gwang, a professor of cultural studies at Kyung Hee University in Seoul.

“Social media is the hotbed of this mirroring. It is human interaction amplified and transplanted to the digital domain. And in building the models we want to resemble in life, we construct an ideal image we want to be, and that becomes the deepfake and the subjectively perfect faces that affect our identities,” said Lee.

Deepfake videos are sophisticated digitally altered or fabricated videos that appear to be realistic but show people doing or saying something they did not.

“To ask if (digital humans) is unnatural would be an oxymoron. Because humans are not natural to begin with. We do things other animals don’t. We may feel ethical discomfort at humans playing god, but this is the innate characteristic of humans that is difficult to change,” Lee said.

However, if the technology is criminally misused to defame others, or spawn discrimination or hatred toward minorities, the matter would demand social scrutiny, Lee added. Lee cited this year’s “Nth room” case, where an online sex crime syndicate offered to create pornographic content using cut-out faces of regular women for those willing to pay.

By Lim Jeong-yeo (kaylalim@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)