S. Korea struggles with unprecedented online learning

Prolonged online learning triggers concerns over educational divide

By Ock Hyun-juPublished : April 22, 2020 - 18:13

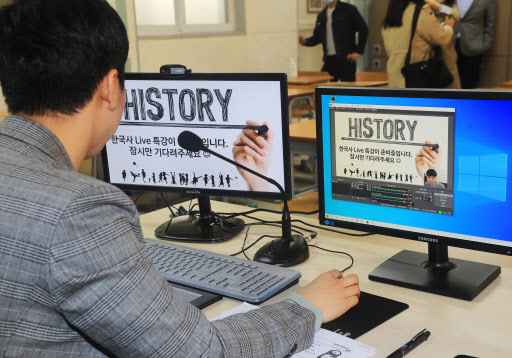

Faced with the novel coronavirus epidemic, South Korea’s schools began offering online classes this month in a step the education minister called a “new road we have never walked.”

Distance learning, however, poses an unprecedented burden to parents and educators, with the quality of education for each student appearing to be closely linked to the level of preparedness of the schools, teachers and parents -- from teachers’ digital literacy to parents’ availability for their children.

The younger the students, the less likely they are to concentrate for longer periods, requiring parents’ help for them to take part in the classes. Not all parents, however, can afford to do that.

“It is impossible for my child to take online classes without me around. It would be better if the semester did not begin at all,” said Park Kyung-ah, parent of a third grader.

“I have to go back to work starting next week. I don’t know what to do.”

Korea began its new spring semester on April 9, one month later than usual, with online classes beginning in phases. School buildings remain physically closed.

Park needed to help her son in logging on to the digital platform, checking in for the class and watching prerecorded education materials, which took less than 30 minutes for each subject. For the rest of the school hours, he did nothing, she said.

“I hope schools can open again soon,” Park said.

For working parents, the only option usually comes down to sending them to “emergency care” classes, which are set up at schools for elementary school students in need of care during the day.

Her child was denied a place due to lack of availability amid soaring demand among working parents who have no one to supervise their children taking online classes at home. Only a limited number of spots are available under the government’s social distancing rules.

Out of 2.72 million elementary school students, 114,550, or 4.2 percent of the students, are being taken care of at emergency classrooms nationwide as of Monday, up from 1.6 percent from March 20, according to data from the Education Ministry.

For now, the ministry said it will give priority to working parents with young children and low-income and single-parent families in securing spots in emergency classrooms.

Those who have more than one child are also struggling to look after all of them at the same time.

“I don’t want schools to open too prematurely, but I am overly stressed because I have to help them attend classes every hour, and my child says the quality of education is low because I am not a qualified teacher,” said Kim Ji-young, the mother of a 9-year-old child.

“It is rather an opening of schools for parents, not for children.”

Park and Kim both told The Korea Herald that their children said they would prefer to go back to their schools.

For teachers, online learning means the amount of their work has doubled.

“The teachers’ office in our school is almost like a call center, with my students constantly calling me to ask questions and I calling them to ask them whether they woke up or whether they uploaded their assignments and so on,” said Jeong Hanna, an eighth-grade teacher on Jeju Island. “While receiving calls, I should answer questions in real time on the online platform.”

“Preparing for classes -- recording, editing and uploading the classes -- also takes so much longer for the online teaching than the offline teaching,” she said.

Park Su-jin, a teacher of elementary school students in their final year, said that she also needs to look after students at emergency care classrooms in her school and has extra work to do such as calling her students’ parents every day.

But her major concern is the widening educational divide stemming from a lack of communication and connection with her students. Those less motivated are just left behind, especially those who have no parents to supervise them, she said.

“If the distance learning were to continue, the gap in students’ smart devices and their capacity to use them should be narrowed,” Park said.

The country’s biggest online learning experiment only sheds light on the existing educational inequality in the country where the quality of education for a student is decided according to parents’ interest and income, an education activist said.

“Korea’s education fever focusing on exams led schools to open hastily online when it was already obvious that unpreparedness among parents, educators and schools would trigger problems such as a lack of equity,” said Gu Bon-chang, a policy director at the World Without Worries about Shadow Education.

Questions also arise over the effectiveness of the shutdown of schools.

While elementary, middle and high schools remain shuttered to help the government’s fight against COVID-19, more and more private cram schools and universities are resuming classes.

Some 82 percent of private cram schools across the country were already in operation as of Friday, despite the government’s recommendation to keep them closed under the social distancing rules.

Four universities nationwide also had opened classrooms on campus as of Wednesday, with four more to follow suit within this month, according to an official from the Korean Association of Private University Presidents.

Most of the country’s universities are scheduled to resume their offline classes in early May.

The Ministry of Education said Tuesday it will decide whether to reopen schools on May 3. There are speculations that offline classes will resume in the second week of May.

The reopening of the country’s elementary, middle and high schools, originally scheduled for March 2, has been pushed back four times amid concerns that enclosed, packed classrooms could host new clusters of infection.

By Ock Hyun-ju (laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Ock Hyun-ju

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)