[News Focus] Energy policy swings with political winds

By Korea HeraldPublished : July 24, 2017 - 16:44

Korea’s energy policy has made an abrupt turn with changes of government in the past few decades, leaving the country short of securing stable, efficient and environmentally sustainable supply of energy.

According to an index released by the World Energy Council last year, it ranked No. 72 and No. 88 out of 125 countries in terms of energy security and environmental sustainability, respectively.

In the latest twist to energy policy, which has swung every five years, President Moon Jae-in’s administration is pushing to phase out nuclear power generation and to replace it with renewable energy.

Concerns have been raised that such a policy shift would result in a hefty rise in electric charges and energy shortage in a country heavily dependent on imports for energy sources.

Some say the new government’s initiatives could end up being discarded by the next administration.

“Energy policy should be pursued based on a long-term vision, given a power plant will be in operation at least for 30 years,” said Kang Seung-jin, a professor at Korea Polytechnic University.

The administration under President Roh Moo-hyun, who served from 2003 to 2008, put the focus of energy policy on curbing electricity demand, giving no approval to the construction of new power plants for three years after its inauguration.

Electricity use soared as the administration of Lee Myung-bak, Roh’s successor, eased demand-curbing measures, causing a massive blackout in September 2011.

The Lee administration scrambled to draw up plans to build a number of new power plants, mainly nuclear and coal-fired ones.

It also aggressively pushed for projects to develop oil, gas and other natural resources abroad to cope with global price hikes and secure a stable supply.

After President Park Geun-hye took over from Lee in 2013, many of the projects were subject to investigation for suspected overpayment and corruption.

With the probe under way, many oil rigs and mining areas owned by Korean companies overseas were sold at what many saw as bargain prices.

The country saw the value of a dozen oil rigs it had sold in the wake of the 1997-98 foreign exchange crisis soar in the following years.

Efforts to encourage the use of renewable energy have also lacked consistency.

As part of its “green growth” drive, the Lee administration put into practice the renewable portfolio standard system, which mandates power utility firms to generate a certain amount of electricity with renewable energy.

But the Park government that succeeded it paid little attention to the matter.

In a recent report to Moon, who took office in May, a presidential advisory committee tasked with setting up key policy tasks proposed generating 20 percent of the country’s electricity with renewable energy by 2030, while reducing reliance on fossil fuels and nuclear power plants. Under the goal, the Moon administration plans to require utility companies with a generation capacity of 500 megawatts or greater to generate 10 percent of their electricity using renewable sources.

Speaking at a ceremony last month to mark the closure of an aged nuclear reactor, Moon vowed to scrap all plans for new nuclear power plants and not to extend the operation of any aged reactors nearing the end of their design life. He also pledged to close at least 10 aged coal-fired power plants.

Apparently affected by his stance, board members at Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Co. decided earlier this month to suspend the construction of two nuclear reactors until a civil panel decides their final fate.

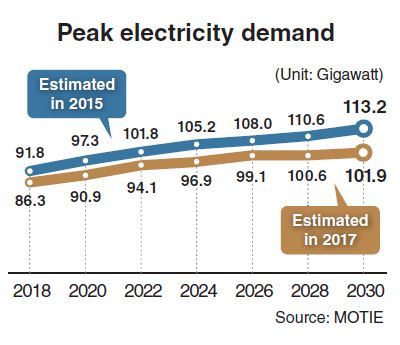

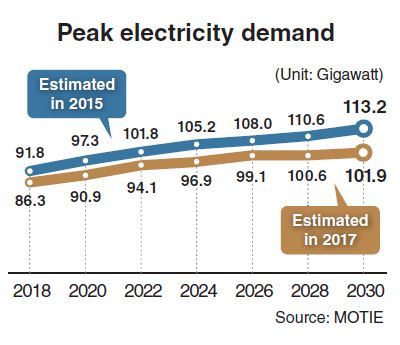

A working group formed by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy recently estimated the peak electricity demand in 2030 would be 10 percent lower than projected two years earlier.

Some suspect the estimate might have been adjusted down to help ease concerns over the new administration’s plan to phase out nuclear power generation, though the group cited the prospect of a slowdown in economic growth as a main reason for the readjustment.

Experts note nuclear power has served to guarantee energy security for the country despite the roller-coasting of energy policy in the past.

Excluding nuclear power generation, Korea’s energy self-sufficiency ratio has hovered slightly over 2 percent in the last few decades.

“It is worrying to push for nuclear power phase-out policy hastily to achieve a tangible outcome in a limited span of time,” said Kang.

Yoon Sang-jik, an opposition lawmaker who formerly served as trade, industry and energy minister, said in a debate last week the effect of the policy to expand the use of renewable energy will be limited due to a shortage of sources, concerns over environmental damage, objections from residents and the need to install back-up facilities.

“Caution is needed against the hasty implementation of nuclear power phase-out policy, which would hamper efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, maintain industrial competitiveness and prepare for the era of the ‘fourth industrial revolution,’” he said.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

According to an index released by the World Energy Council last year, it ranked No. 72 and No. 88 out of 125 countries in terms of energy security and environmental sustainability, respectively.

In the latest twist to energy policy, which has swung every five years, President Moon Jae-in’s administration is pushing to phase out nuclear power generation and to replace it with renewable energy.

Concerns have been raised that such a policy shift would result in a hefty rise in electric charges and energy shortage in a country heavily dependent on imports for energy sources.

Some say the new government’s initiatives could end up being discarded by the next administration.

“Energy policy should be pursued based on a long-term vision, given a power plant will be in operation at least for 30 years,” said Kang Seung-jin, a professor at Korea Polytechnic University.

The administration under President Roh Moo-hyun, who served from 2003 to 2008, put the focus of energy policy on curbing electricity demand, giving no approval to the construction of new power plants for three years after its inauguration.

Electricity use soared as the administration of Lee Myung-bak, Roh’s successor, eased demand-curbing measures, causing a massive blackout in September 2011.

The Lee administration scrambled to draw up plans to build a number of new power plants, mainly nuclear and coal-fired ones.

It also aggressively pushed for projects to develop oil, gas and other natural resources abroad to cope with global price hikes and secure a stable supply.

After President Park Geun-hye took over from Lee in 2013, many of the projects were subject to investigation for suspected overpayment and corruption.

With the probe under way, many oil rigs and mining areas owned by Korean companies overseas were sold at what many saw as bargain prices.

The country saw the value of a dozen oil rigs it had sold in the wake of the 1997-98 foreign exchange crisis soar in the following years.

Efforts to encourage the use of renewable energy have also lacked consistency.

As part of its “green growth” drive, the Lee administration put into practice the renewable portfolio standard system, which mandates power utility firms to generate a certain amount of electricity with renewable energy.

But the Park government that succeeded it paid little attention to the matter.

In a recent report to Moon, who took office in May, a presidential advisory committee tasked with setting up key policy tasks proposed generating 20 percent of the country’s electricity with renewable energy by 2030, while reducing reliance on fossil fuels and nuclear power plants. Under the goal, the Moon administration plans to require utility companies with a generation capacity of 500 megawatts or greater to generate 10 percent of their electricity using renewable sources.

Speaking at a ceremony last month to mark the closure of an aged nuclear reactor, Moon vowed to scrap all plans for new nuclear power plants and not to extend the operation of any aged reactors nearing the end of their design life. He also pledged to close at least 10 aged coal-fired power plants.

Apparently affected by his stance, board members at Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Co. decided earlier this month to suspend the construction of two nuclear reactors until a civil panel decides their final fate.

A working group formed by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy recently estimated the peak electricity demand in 2030 would be 10 percent lower than projected two years earlier.

Some suspect the estimate might have been adjusted down to help ease concerns over the new administration’s plan to phase out nuclear power generation, though the group cited the prospect of a slowdown in economic growth as a main reason for the readjustment.

Experts note nuclear power has served to guarantee energy security for the country despite the roller-coasting of energy policy in the past.

Excluding nuclear power generation, Korea’s energy self-sufficiency ratio has hovered slightly over 2 percent in the last few decades.

“It is worrying to push for nuclear power phase-out policy hastily to achieve a tangible outcome in a limited span of time,” said Kang.

Yoon Sang-jik, an opposition lawmaker who formerly served as trade, industry and energy minister, said in a debate last week the effect of the policy to expand the use of renewable energy will be limited due to a shortage of sources, concerns over environmental damage, objections from residents and the need to install back-up facilities.

“Caution is needed against the hasty implementation of nuclear power phase-out policy, which would hamper efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, maintain industrial competitiveness and prepare for the era of the ‘fourth industrial revolution,’” he said.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Kim Seong-kon] Democracy and the future of South Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050802_0.jpg&u=)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)