Solution still out of reach?

Korea struggling to find ways to preserve prehistoric rock engravings

By Korea HeraldPublished : Jan. 20, 2014 - 19:25

More than 40 years have passed since prehistoric engravings were found on the surface of a rock cliff in Ulsan, about 305 kilometers southeast of Seoul. Over the years, the etchings have been submerged repeatedly because of a nearby dam, but Korea still hasn’t figured out what steps to take to preserve them.

The Bangudae Petroglyph, measuring 3 meters in height and 10 meters in length, was discovered in 1971, six years after Sayeon Dam was built to secure drinking water for Ulsan and prevent flooding.

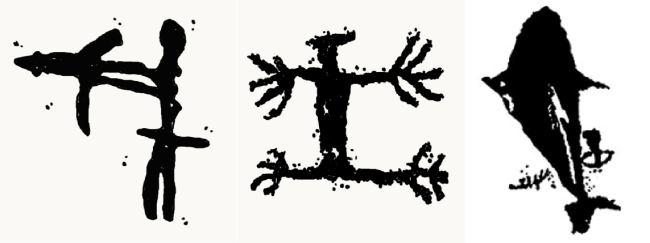

Nearly 300 images of humans, animals, ships, tools and unknown creatures are engraved on the stone wall, which archaeologists say are a key to understanding the people who lived on the Korean Peninsula in prehistoric times.

The Bangudae Petroglyph, measuring 3 meters in height and 10 meters in length, was discovered in 1971, six years after Sayeon Dam was built to secure drinking water for Ulsan and prevent flooding.

Nearly 300 images of humans, animals, ships, tools and unknown creatures are engraved on the stone wall, which archaeologists say are a key to understanding the people who lived on the Korean Peninsula in prehistoric times.

Preservation, a thorny issue

Being underwater repeatedly ― the water rises above the images for more than half the year ― has eroded and damaged the engravings, researchers say.

“We believe the artifact is 25 percent damaged now from the original condition at the time it was created,” said Kang Kyung-hwan, a director at the Cultural Heritage Administration. There is no study available yet as to how much of the damage was caused by the water, he added.

How to preserve the engravings has been one of the thorniest cultural issues in the country, so much so that President Park Geun-hye expressed special interest in it.

Preservationists demand that Ulsan lower the water level of the nearby Sayeon Dam to prevent the site from being submerged again. City officials, however, say such demands are unrealistic because the dam is the main source of water for 1.1 million residents.

A compromise was finally reached last year between Ulsan and the state-run CHA. It calls for construction by October of a transparent, 55-meter-long and 16-meter-high wall to prevent the engravings from being submerged.

The project, however, hit a snag last week when an experts’ panel under the CHA put it off, demanding evidence proving the envisioned weir is just a “temporary measure.”

“We would agree to the construction of the so-called kinetic dam, only when it is a makeshift structure that is going to be in place while a fundamental measure is being drawn up,” Kim Dong-wook, chair of the Architectural Heritage Subcommittee of the Cultural Properties Committee, told reporters Thursday during a briefing on his team’s decision.

His panel has asked Ulsan officials to come up with a detailed plan on what other measure it will take to prevent the submersion fundamentally and when, he added.

The committee’s decision not only suspended the 10 billion won project. It also brought a decade-old controversy back to square one.

“A fundamental solution would be lowering the water level (of Sayeon Dam); that’s why we asked Ulsan how and when it plans to do it,” Kim said.

From the way things look, it is going to take some time for Ulsan to devise such an arrangement.

Lee Chun-sil of Ulsan Metropolitan Government said, “securing an alternative source of water is not something that we, the people of Ulsan, can do on our own.”

In 2009, the city studied the possibility of channeling water from another dam to keep the water level of Sayeon Dam low, but a further study found this infeasible.

The engravings didn’t go under water at all in 2013, as Ulsan suffered a severe drought.

What do the drawings mean?

The Bangudae engravings are presumed to have been made between the late Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. They were designated Korea’s National Treasure No. 285 and were listed in 2011 on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List.

“What is very special about it is that the drawings are highly concentrated on about a 10-meter-wide section of the rock face,” said Moon Myung-dae, the Dongguk University professor who first discovered the petroglyphs. “I knew that it was going to be a very rare find internationally.”

What also attracted the attention of many researchers in Korea and elsewhere were the images of whales ― there were more than 46 depictions of large whales. Researchers believe the Bangudae site contains one of the oldest depictions of whaling.

Whaling seems to have played an important role in social cohesion in the lives of the people who made the petroglyphs, they say.

Some of the drawings illustrate how prehistoric men caught whales ― their use of harpoons, floats and lines. In some images, the whales have what appear to be fleshing lines, where the hunters divided up the meat.

By Lee Sun-young (milaya@heraldcorp.com)

Being underwater repeatedly ― the water rises above the images for more than half the year ― has eroded and damaged the engravings, researchers say.

“We believe the artifact is 25 percent damaged now from the original condition at the time it was created,” said Kang Kyung-hwan, a director at the Cultural Heritage Administration. There is no study available yet as to how much of the damage was caused by the water, he added.

How to preserve the engravings has been one of the thorniest cultural issues in the country, so much so that President Park Geun-hye expressed special interest in it.

Preservationists demand that Ulsan lower the water level of the nearby Sayeon Dam to prevent the site from being submerged again. City officials, however, say such demands are unrealistic because the dam is the main source of water for 1.1 million residents.

A compromise was finally reached last year between Ulsan and the state-run CHA. It calls for construction by October of a transparent, 55-meter-long and 16-meter-high wall to prevent the engravings from being submerged.

The project, however, hit a snag last week when an experts’ panel under the CHA put it off, demanding evidence proving the envisioned weir is just a “temporary measure.”

“We would agree to the construction of the so-called kinetic dam, only when it is a makeshift structure that is going to be in place while a fundamental measure is being drawn up,” Kim Dong-wook, chair of the Architectural Heritage Subcommittee of the Cultural Properties Committee, told reporters Thursday during a briefing on his team’s decision.

His panel has asked Ulsan officials to come up with a detailed plan on what other measure it will take to prevent the submersion fundamentally and when, he added.

The committee’s decision not only suspended the 10 billion won project. It also brought a decade-old controversy back to square one.

“A fundamental solution would be lowering the water level (of Sayeon Dam); that’s why we asked Ulsan how and when it plans to do it,” Kim said.

From the way things look, it is going to take some time for Ulsan to devise such an arrangement.

Lee Chun-sil of Ulsan Metropolitan Government said, “securing an alternative source of water is not something that we, the people of Ulsan, can do on our own.”

In 2009, the city studied the possibility of channeling water from another dam to keep the water level of Sayeon Dam low, but a further study found this infeasible.

The engravings didn’t go under water at all in 2013, as Ulsan suffered a severe drought.

What do the drawings mean?

The Bangudae engravings are presumed to have been made between the late Neolithic period and the Bronze Age. They were designated Korea’s National Treasure No. 285 and were listed in 2011 on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List.

“What is very special about it is that the drawings are highly concentrated on about a 10-meter-wide section of the rock face,” said Moon Myung-dae, the Dongguk University professor who first discovered the petroglyphs. “I knew that it was going to be a very rare find internationally.”

What also attracted the attention of many researchers in Korea and elsewhere were the images of whales ― there were more than 46 depictions of large whales. Researchers believe the Bangudae site contains one of the oldest depictions of whaling.

Whaling seems to have played an important role in social cohesion in the lives of the people who made the petroglyphs, they say.

Some of the drawings illustrate how prehistoric men caught whales ― their use of harpoons, floats and lines. In some images, the whales have what appear to be fleshing lines, where the hunters divided up the meat.

By Lee Sun-young (milaya@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)