Seoul faces tough choices to contain N.K. nuke threat

Experts call for new military strategy, stronger security ties with the U.S.

By 박한나Published : Feb. 6, 2013 - 18:39

South Korea faces a tough task in bolstering its deterrence capabilities against a North Korea feared to emerge as a genuine nuclear power if an impending third test is successful.

Experts said Seoul and Washington should map out a comprehensive deterrence strategy, stressing that North Korean technology to miniaturize nuclear warheads, along with its ballistic missile capability, would pose a grave threat to security on the peninsula and beyond.

Some emphasize a military approach to neutralize the nuclear threat while others stress more cautious, diplomatic methods such as strengthening the security alliance with the U.S. and deferring the transfer of wartime operational control slated for December 2015.

“What is clear as evidenced by its preparation for another nuclear test is that the North has no intention of renouncing its nuclear program,” said Chun In-young, professor emeritus at Seoul National University.

“Whether we recognize its nuclear power status or not, whatever the rhetoric Seoul and Washington may use to describe the North’s nuclear programs, Pyongyang will have crossed the threshold through the next test. Then, Seoul needs to craft a new deterrence strategy.”

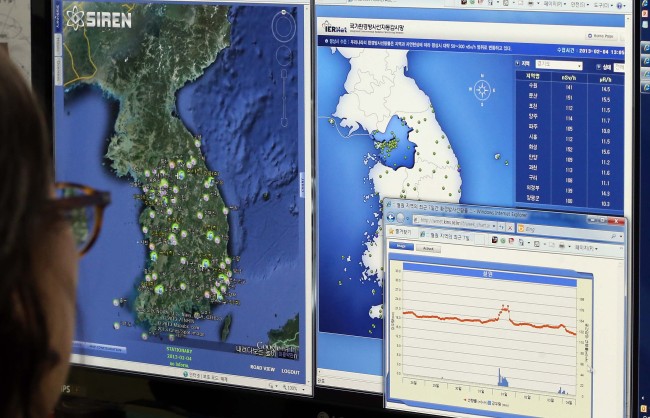

Seoul believes that Pyongyang has already completed preparations for its third nuclear test at its Punggye-ri site in its northeast where it carried out the two previous tests in 2006 and 2009. In December, the North successfully launched a rocket, which experts presume has a potential range of some 10,000 km.

Some military strategists argued that the South could consider “balancing nuclear power” against the North by developing its own nuclear arms or persuading the U.S. to redeploy its tactical nuclear weapons to the peninsula.

Nuclear theorists claim that nuclear weapons are for political, deterrence purposes, as witnessed during the Cold War, which did not escalate into an all-out war between the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union due to the balance of terror stemming from “mutually assured destruction.”

“Theoretically, the only thing that can deter or block nuclear weapons is nuclear weapons,” said Lee Choon-kun, security expert at the Korea Economic Research Institute.

“Although the U.S.’ Barack Obama administration champions the vision of a nuclear-free world, South Korea has a different security environment exposed to a constant nuclear threat from the North. Seoul can ask for the redeployment of tactical nukes on the grounds that it would not build its own nuclear arsenal.”

Some said that Seoul should seek to bring in tactical weapons and could propose to the North mutual nuclear arms reductions given that international diplomatic methods have borne little fruit.

But others argue the disadvantages of bringing nuclear weapons to the South would outweigh the advantages. They cautioned that Seoul could face strong resistance not only from its ally the U.S. but also from the international community upholding the non-proliferation principle, and that its soft power accumulated through its active participation in global issues such as green growth and anti-piracy efforts would be undermined.

Some also pointed out that neighboring states such as China and Japan would not accept a nuclear peninsula due to the possible fallout in case of a nuclear disaster.

“Pyongyang’s pursuit of nuclear arms is driven by political motivations to raise its bargaining power. It is a last-resort political weapon. Thus, I am skeptical about the attempt to resolve a political issue through a military approach such as a preemptive strike,” said Kim Ho-sup, international politics professor at Chung-Ang University.

“Seoul has long committed itself to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which has played a pivotal role to keep world peace. Backing out of it would shake the country’s primary diplomatic policy line as well as the roots of the Korea-U.S. alliance.”

He added that Seoul could propose the delay of the OPCON transfer should security conditions seriously deteriorate after another atomic test in the North.

Another security expert echoed Kim’s view, stressing the importance of maintaining a robust alliance with the U.S.

“The U.S. is confident about its security commitment to the South. In case of an pending nuclear threat, it could launch a nuclear strike from its submarine stationed near Okinawa, Japan. The Obama administration would not do things that would undermine its non-proliferation initiatives,” he said, declining to be named.

“On top of that, it is, in some sense, meaningless for Seoul to seek nuclear arms. It can hardly catch up with others in terms of balancing regional nuclear power. The North is thought to have around 10 warheads while Japan can make many nukes quickly if it determined to do so.”

At the bilateral Extended Deterrence Policy Committee, Seoul and Washington have discussed “tailored deterrence strategy.” The allies are expected to craft a concrete deterrence plan by the end of this year, Seoul officials said. The possible third nuclear test is expected to affect the allies’ discussion over the strategy.

“After a third nuclear test, the threat would become more real. For that, we should map out a stronger, more concrete one that could have a substantive (impact) on the North,” a senior Seoul official told reporters earlier this week.

If nuclear weapons are not an appropriate option for Seoul, it needs to develop asymmetrical capabilities and more sophisticated conventional weapons to fend off the North’s nuclear threats, experts said.

The South can bolster its special operations forces that can be preeminently deployed to the North to eliminate or neutralize the enemy’s strategic arms such as weapons of mass destruction and key command structures.

Seoul can also introduce strategic weapons such as unmanned drones or guided cruise missiles and bunker-busters to destroy key military bases including underground sites where the North’s leadership could hide in case of an emergency or arsenals are stored.

Nam Chang-hee, security expert at Inha University, stressed the need to construct a three-way security cooperation mechanism with the U.S. and Japan; secure capabilities for stealth infiltration; and bolster intelligence-gathering and missile defense capabilities.

“We need to build an intelligence-sharing mechanism for an early detection of North Korean missile launches while at the same time, exerting ‘coercive diplomacy’ to pressure Beijing, which wants to shun the deepening trilateral cooperation, to more actively exert its leverage to curb Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions,” he said.

“Through procuring stealth combat aircraft, we can also develop an operation plan to decapitate the North Korean leadership, so as to present to the North that we have non-nuclear retaliatory capabilities.”

Nam also underscored that to bolster the alliance with the U.S. to help deter the North, Seoul should support the U.S. Forces Korea’s expanding role beyond the peninsula and seek ways to increase South Korea’s strategic security value for Washington.

South Korea has been cautious about obviously supporting the U.S. policy of rebalancing toward the Asia-Pacific for fear of straining ties with China, its largest trade partner.

By Song Sang-ho

(sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)