Koreans in their 30s negative toward establishment, frustrated over economic difficulties

Books on how to become rich have always been steady sellers in Korea, particularly when the economy is suffering. In the first half of this year, however, three books designed to address the concerns of 30-somethings outsold all the get-rich guides put together.

“I find myself absent-mindedly picking up a book with the word 30-somethings in its title every time I visit a bookstore,” said a 32-year-old man who has been preparing for a civil service exam since quitting a private company.

After skimming through a book titled “A 30-Something Inquires of Psychology” in a downtown Seoul bookstore, he bought it. A clerk said the book, by a female psychiatrist, has been popular lately.

Observers such as Bae Jong-chan, managing director at Research&Research, a private polling firm, argue that the increase in sales of books targeting those in their 30s reflects a growing sense of angst. They say the generation is bearing the brunt of a worsening economy and is increasingly uncertain about the future.

“Many in their 30s appear to feel alienated from society and lack direction in life,” Bae said. “They are at a loss as to how to draw up a concrete plan for their future like when to marry or buy a house.”

The trauma of the 1997-8 Asian financial crisis is buried deep in the psyche of that generation, some experts suggest. At such sensitive ages, they were shocked and felt extremely insecure seeing their parents laid off from work or forced to close their businesses.

‘Pessimistic realism’

The impact of the crisis on the generation was particularly acute as it came on the heels of a relatively affluent time during their adolescence. After graduating from school they were forced to compete fiercely for a reduced number of jobs. As a result, those now in their 30s are advised to prepare for uncertainty, said Jeon Sang-jin, professor of sociology at Sogang University in Seoul. This attitude, described by Jeon as “pessimistic realism,” on top of their increasingly difficult working environment, has created a deep-seated sense of angst and anger.

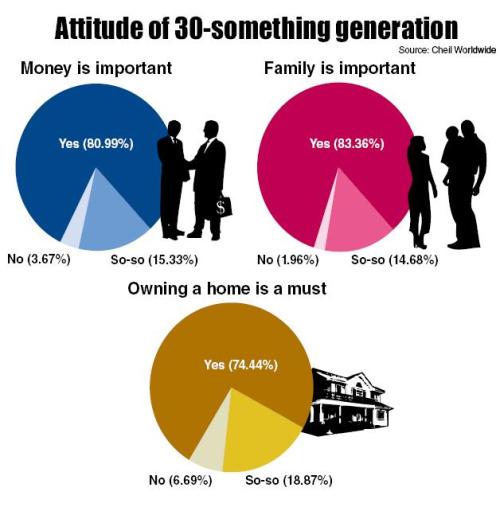

Apparently related to their painful experiences, most people in their 30s place financial stability and family wellbeing above other priorities. In a 2010 survey of about 700 people in their 30s, conducted by advertising company Cheil Worldwide, more than 81 percent of respondents said money was important in life. About 83 percent attached great importance to family life and over 74 percent said owning one’s own home was important.

The generation was exposed to what it was like to be financially vulnerable when they still attended school. They have a different attitude to money than their parents, as they seek to balance work and personal life, unlike the previous generation who devoted their lives to work. Market researchers say they have a pragmatic pattern of consumption, but many in their 30s do not hesitate to spend money on something if they believe it is worth the sum.

Bae indicated that members of this generation also tend to put family at the center of their lives, after seeing their fathers who placed work ahead of their family laid off in the late 1990s.

“They have a strong feeling of responsibility for protecting their own family and think more of basic requirements for family livelihoods than other generations,” he said.

Deteriorating livelihoods

Their aspirations for securing financial stability and a comfortable family life, however, have been thwarted in most cases, by mounting housing costs, price hikes and increasing fees for child care and education.

According to figures from Statistics Korea, consumer prices rose by 5.3 percent from a year earlier in August ― the steepest hike in three years. Home rental costs also increased by 5.1 percent from the year before in the same month, the fastest rise in more than eight years. Despite the government’s measures to slow the rise in rental prices, the total amount of key money deposited by Korean tenants increased by 5.6 trillion won ($4.9 billion) to 583.8 trillion won over the past month, according to figures compiled by a real estate information service company.

Such burdens weigh particularly on 30-somethings, many of whom are preparing to marry, are newlyweds or have young children.

While eager to possess their own home, only 37 percent of those in their 30s do so, according to recent figures from Statistics Korea. A 32-year-old man who rented a small apartment in Seoul two years ago after getting married now faces demands from his landlord for 60 million won more in key money, which would bring the total to 200 million won. He and his wife, who have a child, are searching for a cheaper house on the southern outskirts of Seoul.

Economic hardships, coupled with demographic factors, have caused a growing number of people in their 30s to stay single. According to figures from Statistics Korea, nearly 30 percent of Koreans in their 30s were single at the end of last year. In Seoul, the figure was nearly 40 percent, more than double the 18.4 percent figure a decade earlier. Over 37 percent of Korea’s 30-something men were unmarried, with the figure for women slightly above 20 percent.

The average ages of marriage for men and women were also pushed up to 31.8 and 28.9 in 2010 from 29.3 and 26.5 in 2000, respectively. While some career women with high-paying jobs have difficulties finding spouses of a similar age and economic level, an increasing number of men appear to have given up on marriage as they have no jobs or feel their wages are too low to support a family.

“I think my wage is not on the lower level but I am not sure it will be sufficient to support my family,” said a 33-year-old company employee who remains single, identifying himself by his family name Kim.

Delaying marriage has specific implications for women in their 30s as the main age group for childbirth. According to government figures, the annual number of childbirths per 1,000 women in their 30s averaged 145.3 last year, compared to 96 for women in their 20s. The increase in the age of first delivery, coupled with rising costs for raising and educating children, has given Korea the world’s lowest fertility rate, experts note.

A 35-year-old woman surnamed Lee, who wants to return to work after two years off to care for her daughter, felt frustrated recently when she was told by an official at a child care center run by her ward office in Seoul that more than 100 children were already on the waiting list.

Their deteriorating livelihoods and uncertain futures have led the 30-somenthing generation to be more critical of social problems, experts say.

“Many in the generation appear to have given in to the resignation that they will be unable to be wealthy on their own under the constraints of the established economic and social systems,” said Bae.

According to a recent research by the polling firm, nearly half of Koreans in their 30s believe the conflict between the poor and the rich is “very serious,” with slightly less than 40 percent replying that it is “somewhat serious.”

The generation also shows a more negative sentiment toward big businesses. In a survey conducted by the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry in July, only 48.3 percent of respondents in their 30s expressed favor with large firms, compared to 53.8 for people in their 50s and 51.3 for those in their 40s.

Political antipathy

Political analysts indicate their frustration has made them angry with the main political parties, which have failed to address their concerns. Their resentment is especially targeted at President Lee Myung-bak and his ruling Grand National Party. They feel betrayed by Lee’s economic policies, under which the gap between rich and poor has widened, as they voted for him hoping that the former construction firm CEO would improve their conditions.

GNP officials were stunned early this year when their survey of housewives in their 30s found that more than 80 percent of them disliked the ruling party, complaining about the sharp rise in housing costs, food prices and nursing fees.

Analysts indicate that this sentiment is behind the swings in voting patterns between conservative and liberal political forces in recent years.

More than 70 percent of voters expressed antipathy toward liberal President Roh Moo-hyun in 2007 and an overwhelming majority of them supported President Lee during his election that year. But about 70 percent of those who voted in last April’s by-election in a conservative district cast ballots for Sohn Hak-kyu, leader of a liberal main opposition party. Such voter swings cannot be understood in terms of ideological change and reflect the frustration and anger resulting from economic problems, particularly among those in their 30s, analysts say.

The GNP fears defeat in April’s parliamentary elections, while the opposition expresses confidence in winning the election.

Entrepreneur-turned-professor Ahn Cheol-soo, whose popularity among voters has rocked political circles since he was first touted as a potential presidential candidate early this month, said in a recent interview that the anger of Koreans in their 20s and 30s would increase voter turnout in next year’s parliamentary and presidential elections.

Reflecting their antipathy toward major parties, those in their 30s tend to remain nonpartisan. According to a recent nationwide survey of 1,000 voters, 31.3 percent of respondents in their 30s said they would support an independent candidate in the upcoming parliamentary elections. The proportion was 31.1 percent for voters in their 20s, 28.6 percent for those in their 40s and 17.6 percent for those in their 50s.

The reality for many 30-somethings sharply contrasts their expectations a decade ago that they would be the first truly open and globalized generation of Koreans. The generation born in the period when Korea was on the track toward rapid economic development became proud of their nation growing up. They made up the bulk of the crowds who packed Seoul’s plazas during the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup when the Korean team advanced to the semifinals.

Bae noted some of this positivity seems to remain, citing the outcome of a survey, in which more than 50 percent of those in their 30s said they were ready to defend the country in a war, while less than 40 percent of those in their 20s said they would.

“How to embrace the members of this generation, who are supposed to play a pivotal dynamic role in society but are at a loss what they can expect from their future, should be a main task for political circles,” he said. “Whether they can successfully carry it out will hold a key to the integration and further advancement of our society.”

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

Books on how to become rich have always been steady sellers in Korea, particularly when the economy is suffering. In the first half of this year, however, three books designed to address the concerns of 30-somethings outsold all the get-rich guides put together.

“I find myself absent-mindedly picking up a book with the word 30-somethings in its title every time I visit a bookstore,” said a 32-year-old man who has been preparing for a civil service exam since quitting a private company.

After skimming through a book titled “A 30-Something Inquires of Psychology” in a downtown Seoul bookstore, he bought it. A clerk said the book, by a female psychiatrist, has been popular lately.

Observers such as Bae Jong-chan, managing director at Research&Research, a private polling firm, argue that the increase in sales of books targeting those in their 30s reflects a growing sense of angst. They say the generation is bearing the brunt of a worsening economy and is increasingly uncertain about the future.

“Many in their 30s appear to feel alienated from society and lack direction in life,” Bae said. “They are at a loss as to how to draw up a concrete plan for their future like when to marry or buy a house.”

The trauma of the 1997-8 Asian financial crisis is buried deep in the psyche of that generation, some experts suggest. At such sensitive ages, they were shocked and felt extremely insecure seeing their parents laid off from work or forced to close their businesses.

‘Pessimistic realism’

The impact of the crisis on the generation was particularly acute as it came on the heels of a relatively affluent time during their adolescence. After graduating from school they were forced to compete fiercely for a reduced number of jobs. As a result, those now in their 30s are advised to prepare for uncertainty, said Jeon Sang-jin, professor of sociology at Sogang University in Seoul. This attitude, described by Jeon as “pessimistic realism,” on top of their increasingly difficult working environment, has created a deep-seated sense of angst and anger.

Apparently related to their painful experiences, most people in their 30s place financial stability and family wellbeing above other priorities. In a 2010 survey of about 700 people in their 30s, conducted by advertising company Cheil Worldwide, more than 81 percent of respondents said money was important in life. About 83 percent attached great importance to family life and over 74 percent said owning one’s own home was important.

The generation was exposed to what it was like to be financially vulnerable when they still attended school. They have a different attitude to money than their parents, as they seek to balance work and personal life, unlike the previous generation who devoted their lives to work. Market researchers say they have a pragmatic pattern of consumption, but many in their 30s do not hesitate to spend money on something if they believe it is worth the sum.

Bae indicated that members of this generation also tend to put family at the center of their lives, after seeing their fathers who placed work ahead of their family laid off in the late 1990s.

“They have a strong feeling of responsibility for protecting their own family and think more of basic requirements for family livelihoods than other generations,” he said.

Deteriorating livelihoods

Their aspirations for securing financial stability and a comfortable family life, however, have been thwarted in most cases, by mounting housing costs, price hikes and increasing fees for child care and education.

According to figures from Statistics Korea, consumer prices rose by 5.3 percent from a year earlier in August ― the steepest hike in three years. Home rental costs also increased by 5.1 percent from the year before in the same month, the fastest rise in more than eight years. Despite the government’s measures to slow the rise in rental prices, the total amount of key money deposited by Korean tenants increased by 5.6 trillion won ($4.9 billion) to 583.8 trillion won over the past month, according to figures compiled by a real estate information service company.

Such burdens weigh particularly on 30-somethings, many of whom are preparing to marry, are newlyweds or have young children.

While eager to possess their own home, only 37 percent of those in their 30s do so, according to recent figures from Statistics Korea. A 32-year-old man who rented a small apartment in Seoul two years ago after getting married now faces demands from his landlord for 60 million won more in key money, which would bring the total to 200 million won. He and his wife, who have a child, are searching for a cheaper house on the southern outskirts of Seoul.

Economic hardships, coupled with demographic factors, have caused a growing number of people in their 30s to stay single. According to figures from Statistics Korea, nearly 30 percent of Koreans in their 30s were single at the end of last year. In Seoul, the figure was nearly 40 percent, more than double the 18.4 percent figure a decade earlier. Over 37 percent of Korea’s 30-something men were unmarried, with the figure for women slightly above 20 percent.

The average ages of marriage for men and women were also pushed up to 31.8 and 28.9 in 2010 from 29.3 and 26.5 in 2000, respectively. While some career women with high-paying jobs have difficulties finding spouses of a similar age and economic level, an increasing number of men appear to have given up on marriage as they have no jobs or feel their wages are too low to support a family.

“I think my wage is not on the lower level but I am not sure it will be sufficient to support my family,” said a 33-year-old company employee who remains single, identifying himself by his family name Kim.

Delaying marriage has specific implications for women in their 30s as the main age group for childbirth. According to government figures, the annual number of childbirths per 1,000 women in their 30s averaged 145.3 last year, compared to 96 for women in their 20s. The increase in the age of first delivery, coupled with rising costs for raising and educating children, has given Korea the world’s lowest fertility rate, experts note.

A 35-year-old woman surnamed Lee, who wants to return to work after two years off to care for her daughter, felt frustrated recently when she was told by an official at a child care center run by her ward office in Seoul that more than 100 children were already on the waiting list.

Their deteriorating livelihoods and uncertain futures have led the 30-somenthing generation to be more critical of social problems, experts say.

“Many in the generation appear to have given in to the resignation that they will be unable to be wealthy on their own under the constraints of the established economic and social systems,” said Bae.

According to a recent research by the polling firm, nearly half of Koreans in their 30s believe the conflict between the poor and the rich is “very serious,” with slightly less than 40 percent replying that it is “somewhat serious.”

The generation also shows a more negative sentiment toward big businesses. In a survey conducted by the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry in July, only 48.3 percent of respondents in their 30s expressed favor with large firms, compared to 53.8 for people in their 50s and 51.3 for those in their 40s.

Political antipathy

Political analysts indicate their frustration has made them angry with the main political parties, which have failed to address their concerns. Their resentment is especially targeted at President Lee Myung-bak and his ruling Grand National Party. They feel betrayed by Lee’s economic policies, under which the gap between rich and poor has widened, as they voted for him hoping that the former construction firm CEO would improve their conditions.

GNP officials were stunned early this year when their survey of housewives in their 30s found that more than 80 percent of them disliked the ruling party, complaining about the sharp rise in housing costs, food prices and nursing fees.

Analysts indicate that this sentiment is behind the swings in voting patterns between conservative and liberal political forces in recent years.

More than 70 percent of voters expressed antipathy toward liberal President Roh Moo-hyun in 2007 and an overwhelming majority of them supported President Lee during his election that year. But about 70 percent of those who voted in last April’s by-election in a conservative district cast ballots for Sohn Hak-kyu, leader of a liberal main opposition party. Such voter swings cannot be understood in terms of ideological change and reflect the frustration and anger resulting from economic problems, particularly among those in their 30s, analysts say.

The GNP fears defeat in April’s parliamentary elections, while the opposition expresses confidence in winning the election.

Entrepreneur-turned-professor Ahn Cheol-soo, whose popularity among voters has rocked political circles since he was first touted as a potential presidential candidate early this month, said in a recent interview that the anger of Koreans in their 20s and 30s would increase voter turnout in next year’s parliamentary and presidential elections.

Reflecting their antipathy toward major parties, those in their 30s tend to remain nonpartisan. According to a recent nationwide survey of 1,000 voters, 31.3 percent of respondents in their 30s said they would support an independent candidate in the upcoming parliamentary elections. The proportion was 31.1 percent for voters in their 20s, 28.6 percent for those in their 40s and 17.6 percent for those in their 50s.

The reality for many 30-somethings sharply contrasts their expectations a decade ago that they would be the first truly open and globalized generation of Koreans. The generation born in the period when Korea was on the track toward rapid economic development became proud of their nation growing up. They made up the bulk of the crowds who packed Seoul’s plazas during the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup when the Korean team advanced to the semifinals.

Bae noted some of this positivity seems to remain, citing the outcome of a survey, in which more than 50 percent of those in their 30s said they were ready to defend the country in a war, while less than 40 percent of those in their 20s said they would.

“How to embrace the members of this generation, who are supposed to play a pivotal dynamic role in society but are at a loss what they can expect from their future, should be a main task for political circles,” he said. “Whether they can successfully carry it out will hold a key to the integration and further advancement of our society.”

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)