Styron’s youngest daughter pens revealing memoir

Reading My Father: A Memoir

By Alexandra Styron

(Scribner, $25)

A decade after the publication of his last, lavishly acclaimed novel, “Sophie’s Choice,” William Styron wrote about his epic struggle with incapacitating depression.

It was, as his youngest daughter, Alexandra, writes in a compelling new memoir, before Kay Jamison, Andrew Sullivan or other fellow sufferers had journeyed “back from the fresh hell of depression with any cogent field notes.”

His essay drew an enormous outpouring from people whose lives had been touched by the terrible illness. Now Alexandra, herself a writer, tells what it was like to grow up in a household defined not only by her father’s outsize talent, but also by his monumental self-absorption and turbulent moods.

The youngest of four children, Alexandra Styron knew never to bother her father when he was working. The whole family was so terrified of him that once, when she was just a baby and had fallen down a flight of stairs headfirst onto concrete, her older siblings waited an hour for their mother to get home to report the injury rather than bother “Daddy” while he was napping.

The elder Styron did not just suffer from the absent-minded navel-gazing one might expect of a writer. He had a mean streak, evident in the horror stories he told her, including one about a homicidal maniac who stashed his victims’ remains in the attic of their rural farmhouse. Another time, he glanced up from his paper and told the little girl he called “Al” or “Albert” -- a pony owner, passionate about riding -- that the Connecticut governor had banned horses and theirs would have to go to the glue factory.

When Alexandra was invited to write a book about Styron after his 2006 death, she felt she had “mentally misplaced” him. What memories remained were dark and puzzling, the source of years of anger that at one point drove her into thrice-weekly psychoanalysis. She began commuting to Duke University, her father’s alma mater, where his papers are housed. She interviewed his dear friend and fellow writer Peter Matthiessen and longtime editor Bob Loomis.

Her memoir, “Reading My Father,” traces the arc of her father’s life, from his boyhood in Tidewater, Virginia, to his years as a platinum-plated member of the hard-drinking, womanizing male writers’ club whose defining experience was World War II.

The writing helps her methodically dismantle “the armor I’d successfully constructed against the chaos of my childhood.” In the process, she discovers not only the complex origins of her father’s suffering but also what he taught her, without ever meaning to, about how to live life as a writer. (AP)

‘Leaving van Gogh’ a revealing portrait of doubt

Leaving van Gogh

By Carol Wallace

(Spiegel & Grau, $25)

Although he merely dabbled with paint and brush, French physician Paul Gachet occupies a significant place in art history.

The intriguing novel “Leaving van Gogh” imagines what the good doctor might say in looking back on the two months in 1890 during which he tried -- and failed -- to rescue the painter Vincent van Gogh from madness.

Author Carol Wallace’s sympathetic portrait of van Gogh is secondary to that of Gachet himself, a man of science who marvels at the artistic talent of his 37-year-old patient. He treats van Gogh’s mental illness with modern methods, at least for the late 19th century. His chief tool is a sense of compassion for the tortured soul.

Just as van Gogh studies Gachet and others for portraits during his stay in the French countryside, Wallace offers her own study of the doctor. He mourns a dead wife, tries to be a good father to a blossoming young daughter and maturing teenage son, and seeks worth in a practice that often deals with the deranged.

Gachet is aware that he, too, is on an emotional tightrope at times, if not as lacking as van Gogh in maintaining mental balance. He shares another quality with the troubled artist: self-doubt. In Wallace’s rendering, the doctor’s memories are colored by the elation that comes from having discovered a genius in his midst -- and the knowledge that the tragedy that lies ahead, like his wife’s fatal illness, proves to be beyond his powers to prevent.

Many readers will come to “Leaving van Gogh” with their own knowledge of the painter’s life. (The famous incident in which he cut off part of an ear took place before he met Gachet.) In sublime prose, Wallace subtly refers to van Gogh’s artworks, and his signature style, as she allows Gachet the opportunity to lift the burden of regret from his mind.

Most appropriately, a sense of melancholy marks “Leaving van Gogh,” though it makes the novel no less enjoyable. And there is no small amount of irony attached to the subject of van Gogh and Gachet: In 1990, van Gogh’s portrait of the doctor sold for $82.5 million, then the highest price paid at auction for a work of art. In his lifetime, van Gogh managed to sell but a single painting. (AP)

Colorful compendium offers glimpse into work life

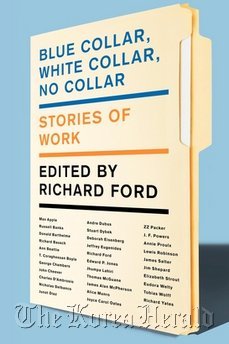

Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar

Edited by Richard Ford

(Harper Perennial, $16.99)

Work -- it can offer validity and a means of escape. Help fight loneliness and boost self-esteem. Possibly sink relationships or improve one’s social standing.

Such theories are explored in a collection of 32 short stories titled, “Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar” (Harper Perennial), edited by Richard Ford. It is a rich compendium that seeks to define, defend and explain the importance of work using complex characters that range from a veteran waiter aboard a train to a lauded but aging poet seeking his muse in Italy.

Most societies rely on work to help define, judge, idolize or shun a person, and many succumb to the urge of asking someone they just met what exactly they do for a living -- a practice that Ford writes is often regarded as impolite and aggressive.

“It was as if doing such a garish thing one would basically be saying, ‘Well, now... what makes you so goddamn sure you’re solid on the earth?’”

But it is exactly this suggestion that indirectly or directly drives most of the protagonists.

The masterpiece in this collection is quite possibly “A Solo Song: For Doc” by James Alan McPherson. Never has a narrative about a waiter serving a passenger aboard a train been so suspenseful, or the description of a job so compelling. In the story, a black man who has worked aboard trains nearly all his life fights for his job with steely persistence despite bosses who try to force him to quit after decades of successful service.

His reason for defending his job is simple: “There were no civil rights or marches or riots for something better in those days. In those days a man found something he liked to do and liked it from then on because he couldn’t help himself.”

Other stories explore the satisfaction derived from work, and how work often becomes an organic extension of oneself.

In “Drummond & Son,” Charles D’Ambrosio relies on sharp imagery to describe a man who fixes typewriters for a living: “As far back as Drummond could recall, he’d had typewriter parts in his pockets and ink in the crevices of his fingers and a light sheen of Remington gun oil on his skin.”

Work also can be a source of security and comfort when it indulges one’s personality traits, as seen in “High Lonesome” by Joyce Carol Oates: “In school, saluting the American flag felt good to him. Reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. Wearing the Beechum County Sheriff’s Department uniform. Keeping his weapon clean.”

But for all its fulfilling aspects, work is largely driven by need, greed and expectations, often leading to a frustrated life best described by Jeffrey Eugenides in the “Great Experiment,” which captures the dull reality of a man struggling to support his middle-class family.

“In this real world, there were things like custom software and ownership percentages and Machiavellian corporate struggles, all of which resulted in the ability to drive a heartbreakingly beautiful forest-green Range Rover up your own paved drive,” he writes.

Most stories in the collection are based in the U.S., leading to a somewhat monotonous reading experience brilliantly broken up by the “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri, who offers a refreshing, one-sided love story between a tour guide in India and a female tourist.

The collection also includes a short story by Junot Diaz, “Edison, New Jersey,” which portrays the everyday life of blue-collar workers in stark terms: “I sit next to this three-hundred-pound rock-and-roll chick who washes dishes at the Friendly’s. She tells me about the roaches she kills with her water nozzle. Boils the wings right off them.”

The book’s release comes as the U.S. unemployment rate drops to its lowest level in two years and as U.S. businesses try to recover from a global economic crisis, posting the largest number of job openings in more than two years.

The sting of the crisis, and the massive layoffs that ensued, recalls a passage in “The Deposition,” by Tobias Wolff, published in the New Yorker in 2006: “Burke knew the whole story, and it disgusted him -- especially the workers who’d let the owners screw them like this while patting them on the head, congratulating them for being the backbone of the country, salt of the earth, the true Americans.” (AP)

Reading My Father: A Memoir

By Alexandra Styron

(Scribner, $25)

A decade after the publication of his last, lavishly acclaimed novel, “Sophie’s Choice,” William Styron wrote about his epic struggle with incapacitating depression.

It was, as his youngest daughter, Alexandra, writes in a compelling new memoir, before Kay Jamison, Andrew Sullivan or other fellow sufferers had journeyed “back from the fresh hell of depression with any cogent field notes.”

His essay drew an enormous outpouring from people whose lives had been touched by the terrible illness. Now Alexandra, herself a writer, tells what it was like to grow up in a household defined not only by her father’s outsize talent, but also by his monumental self-absorption and turbulent moods.

The youngest of four children, Alexandra Styron knew never to bother her father when he was working. The whole family was so terrified of him that once, when she was just a baby and had fallen down a flight of stairs headfirst onto concrete, her older siblings waited an hour for their mother to get home to report the injury rather than bother “Daddy” while he was napping.

The elder Styron did not just suffer from the absent-minded navel-gazing one might expect of a writer. He had a mean streak, evident in the horror stories he told her, including one about a homicidal maniac who stashed his victims’ remains in the attic of their rural farmhouse. Another time, he glanced up from his paper and told the little girl he called “Al” or “Albert” -- a pony owner, passionate about riding -- that the Connecticut governor had banned horses and theirs would have to go to the glue factory.

When Alexandra was invited to write a book about Styron after his 2006 death, she felt she had “mentally misplaced” him. What memories remained were dark and puzzling, the source of years of anger that at one point drove her into thrice-weekly psychoanalysis. She began commuting to Duke University, her father’s alma mater, where his papers are housed. She interviewed his dear friend and fellow writer Peter Matthiessen and longtime editor Bob Loomis.

Her memoir, “Reading My Father,” traces the arc of her father’s life, from his boyhood in Tidewater, Virginia, to his years as a platinum-plated member of the hard-drinking, womanizing male writers’ club whose defining experience was World War II.

The writing helps her methodically dismantle “the armor I’d successfully constructed against the chaos of my childhood.” In the process, she discovers not only the complex origins of her father’s suffering but also what he taught her, without ever meaning to, about how to live life as a writer. (AP)

‘Leaving van Gogh’ a revealing portrait of doubt

Leaving van Gogh

By Carol Wallace

(Spiegel & Grau, $25)

Although he merely dabbled with paint and brush, French physician Paul Gachet occupies a significant place in art history.

The intriguing novel “Leaving van Gogh” imagines what the good doctor might say in looking back on the two months in 1890 during which he tried -- and failed -- to rescue the painter Vincent van Gogh from madness.

Author Carol Wallace’s sympathetic portrait of van Gogh is secondary to that of Gachet himself, a man of science who marvels at the artistic talent of his 37-year-old patient. He treats van Gogh’s mental illness with modern methods, at least for the late 19th century. His chief tool is a sense of compassion for the tortured soul.

Just as van Gogh studies Gachet and others for portraits during his stay in the French countryside, Wallace offers her own study of the doctor. He mourns a dead wife, tries to be a good father to a blossoming young daughter and maturing teenage son, and seeks worth in a practice that often deals with the deranged.

Gachet is aware that he, too, is on an emotional tightrope at times, if not as lacking as van Gogh in maintaining mental balance. He shares another quality with the troubled artist: self-doubt. In Wallace’s rendering, the doctor’s memories are colored by the elation that comes from having discovered a genius in his midst -- and the knowledge that the tragedy that lies ahead, like his wife’s fatal illness, proves to be beyond his powers to prevent.

Many readers will come to “Leaving van Gogh” with their own knowledge of the painter’s life. (The famous incident in which he cut off part of an ear took place before he met Gachet.) In sublime prose, Wallace subtly refers to van Gogh’s artworks, and his signature style, as she allows Gachet the opportunity to lift the burden of regret from his mind.

Most appropriately, a sense of melancholy marks “Leaving van Gogh,” though it makes the novel no less enjoyable. And there is no small amount of irony attached to the subject of van Gogh and Gachet: In 1990, van Gogh’s portrait of the doctor sold for $82.5 million, then the highest price paid at auction for a work of art. In his lifetime, van Gogh managed to sell but a single painting. (AP)

Colorful compendium offers glimpse into work life

Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar

Edited by Richard Ford

(Harper Perennial, $16.99)

Work -- it can offer validity and a means of escape. Help fight loneliness and boost self-esteem. Possibly sink relationships or improve one’s social standing.

Such theories are explored in a collection of 32 short stories titled, “Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar” (Harper Perennial), edited by Richard Ford. It is a rich compendium that seeks to define, defend and explain the importance of work using complex characters that range from a veteran waiter aboard a train to a lauded but aging poet seeking his muse in Italy.

Most societies rely on work to help define, judge, idolize or shun a person, and many succumb to the urge of asking someone they just met what exactly they do for a living -- a practice that Ford writes is often regarded as impolite and aggressive.

“It was as if doing such a garish thing one would basically be saying, ‘Well, now... what makes you so goddamn sure you’re solid on the earth?’”

But it is exactly this suggestion that indirectly or directly drives most of the protagonists.

The masterpiece in this collection is quite possibly “A Solo Song: For Doc” by James Alan McPherson. Never has a narrative about a waiter serving a passenger aboard a train been so suspenseful, or the description of a job so compelling. In the story, a black man who has worked aboard trains nearly all his life fights for his job with steely persistence despite bosses who try to force him to quit after decades of successful service.

His reason for defending his job is simple: “There were no civil rights or marches or riots for something better in those days. In those days a man found something he liked to do and liked it from then on because he couldn’t help himself.”

Other stories explore the satisfaction derived from work, and how work often becomes an organic extension of oneself.

In “Drummond & Son,” Charles D’Ambrosio relies on sharp imagery to describe a man who fixes typewriters for a living: “As far back as Drummond could recall, he’d had typewriter parts in his pockets and ink in the crevices of his fingers and a light sheen of Remington gun oil on his skin.”

Work also can be a source of security and comfort when it indulges one’s personality traits, as seen in “High Lonesome” by Joyce Carol Oates: “In school, saluting the American flag felt good to him. Reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. Wearing the Beechum County Sheriff’s Department uniform. Keeping his weapon clean.”

But for all its fulfilling aspects, work is largely driven by need, greed and expectations, often leading to a frustrated life best described by Jeffrey Eugenides in the “Great Experiment,” which captures the dull reality of a man struggling to support his middle-class family.

“In this real world, there were things like custom software and ownership percentages and Machiavellian corporate struggles, all of which resulted in the ability to drive a heartbreakingly beautiful forest-green Range Rover up your own paved drive,” he writes.

Most stories in the collection are based in the U.S., leading to a somewhat monotonous reading experience brilliantly broken up by the “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri, who offers a refreshing, one-sided love story between a tour guide in India and a female tourist.

The collection also includes a short story by Junot Diaz, “Edison, New Jersey,” which portrays the everyday life of blue-collar workers in stark terms: “I sit next to this three-hundred-pound rock-and-roll chick who washes dishes at the Friendly’s. She tells me about the roaches she kills with her water nozzle. Boils the wings right off them.”

The book’s release comes as the U.S. unemployment rate drops to its lowest level in two years and as U.S. businesses try to recover from a global economic crisis, posting the largest number of job openings in more than two years.

The sting of the crisis, and the massive layoffs that ensued, recalls a passage in “The Deposition,” by Tobias Wolff, published in the New Yorker in 2006: “Burke knew the whole story, and it disgusted him -- especially the workers who’d let the owners screw them like this while patting them on the head, congratulating them for being the backbone of the country, salt of the earth, the true Americans.” (AP)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)