[Herald Interview] ‘I am a Nepalese who interprets for Nepalese asylum seekers’

Translation services crucial in refugee screening process but in short supply

By Choi Jae-heePublished : July 4, 2022 - 18:27

Sujan Shakya is perhaps the most famous Nepalese in Korea now.

Having starred in JTBC’s multinational talk show “Non-Summit” and MBC Every 1’s reality travel show “Welcome, First Time in Korea?” the 34-year-old is among those foreign residents who found fame here.

He is less well-known for his work as an interpreter for other Nepalese seeking asylum in Korea.

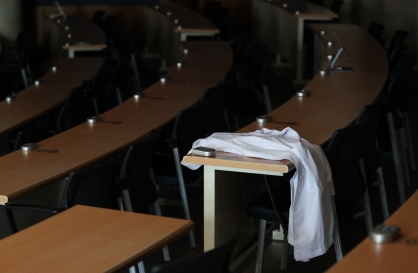

Almost every week, he meets two or three refugee applicants from Nepal at the Seoul Immigration Office in Yangcheon-gu.

As they go through asylum interviews one by one, he goes between the interviewer and the interviewee, translating Korean into Nepalese and vice versa.

Shakya is one of about 250 interpreters hired by the Justice Ministry to help with the refugee application and screening process.

“My job is to accurately translate what the asylum seekers say into Korean to help with the refugee screening process. I’m not allowed to defend a refugee applicant nor add to the conversation, but I can offer immigration officials some explanations about socio-political issues in Nepal after the interview,” Shakya said in an interview with The Korea Herald.

Life-changing interpretation

According to Shakya, who has been working with the Justice Ministry since 2019, a refugee’s life could depend on words that come from interpreters.

"If a refugee says he has been physically threatened by someone, his interpreter must not omit the word ‘physically’ when translating his remarks into Korean. Otherwise, he might become a lower priority for examiners," id Shakya, who has lived in Korea for 12 years.

Besides acting as a go-between, the interpreter’s task can also involve reviewing documents filed by the applicants, he added.

Applicants sometimes hand in documents issued by organizations in their country or some news articles written in their native language as proof of their identity, past activities, or the home country’s unstable social and political conditions.

In that case, the immigration official could ask for help reviewing those papers, he added.

Mindful of the public sentiment here, which is not particularly welcoming of refugees, Shakya stressed that his role as an interpreter is not to help refugee status applicants to get what they want. It is to enhance the screening and assessment process so that those who truly need refugee protection can be identified.

"I’m not working … to lead the Korean government officials to accept more refugees, neglecting public worries over fake refugees, but to improve the current screening system for refugee acceptance by assisting communication," he said.

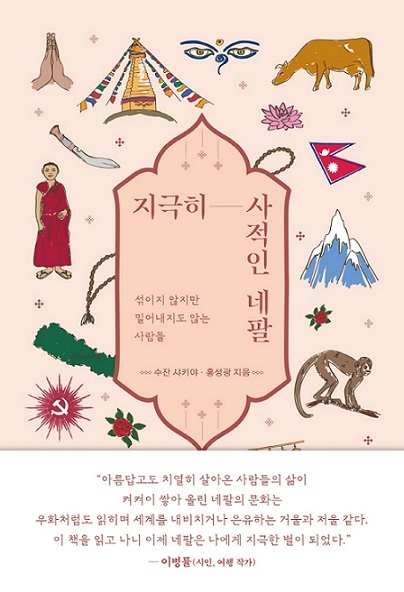

As a Nepalese working and living in Korea, he feels that there is work that he can do to bridge the two countries he loves. As part of such efforts, he has recently published a book in Korean about Nepal. Co-authored by Hong Sung-kwang, “Utmost and Personal Nepal” introduces the South Asian country’s culture and values.

"In Nepal, shaking one’s head is interpreted as ‘yes.’ Imagine I wobble my head in front of my boss. He will get offended for sure. This kind of cultural difference can lead to the misconception that the Nepalese are rude. Unless people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds openly discuss their differences, racism and xenophobia stemming from cultural misunderstandings will continue."

Interpreters in short supply

Across the world, the number of refugees has nearly doubled over the past decade -- from 10.5 million in 2010 to 20.7 million in 2020, which has now reached 21.3 million at the end of 2021, according to the UNHCR.

South Korea has seen a surge in asylum applications as well, from less than 500 in 2010 to over 15,000 in 2019, before the pandemic caused a sharp reduction in numbers. Last year, a total of 2,341 foreigners applied for refugee status here, comprising 301 Chinese, 233 Bangladeshis, 164 Nigerians, 148 Indians and 131 Pakistanis, according to Statistics Korea.

But the nation lacks the workforce to handle the applications, which involve a lot of paperwork and translation.

Since 2012, the Ministry of Justice’s refugee policy division has annually recruited both Koreans and foreign nationals with the capacity to interpret for refugee applicants. In its most recent hiring late last year, the ministry had secured about 160 new interpreters, who started work in January this year.

Interpreters in short supply

Across the world, the number of refugees has nearly doubled over the past decade -- from 10.5 million in 2010 to 20.7 million in 2020, which has now reached 21.3 million at the end of 2021, according to the UNHCR.

South Korea has seen a surge in asylum applications as well, from less than 500 in 2010 to over 15,000 in 2019, before the pandemic caused a sharp reduction in numbers. Last year, a total of 2,341 foreigners applied for refugee status here, comprising 301 Chinese, 233 Bangladeshis, 164 Nigerians, 148 Indians and 131 Pakistanis, according to Statistics Korea.

But the nation lacks the workforce to handle the applications, which involve a lot of paperwork and translation.

Since 2012, the Ministry of Justice’s refugee policy division has annually recruited both Koreans and foreign nationals with the capacity to interpret for refugee applicants. In its most recent hiring late last year, the ministry had secured about 160 new interpreters, who started work in January this year.

The hiring process entails resume screening, a written test and an interview. Once selected, the interpreters work as freelancers, conducting consecutive interpreting during refugee interviews when there is a request. The pay is 50,000 won ($38.55) per hour.

The ministry’s current pool of interpreters consists mainly of college students, office workers and married immigrants. Some 40 percent of them are foreigners.

"Last year, the majority of applicants were for English or Chinese, while those who applied for minor languages were in single digits," said a Justice Ministry official.

Currently, there are only one or two interpreters who can assist asylum seekers from Myanmar, Cambodia, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and Kazakhstan, the official added.

Some experts suggest that more incentives may be needed to draw public interest in interpretation work for refugees.

"Under the pressure of negative public sentiment toward refugee acceptance, the government has been reluctant to increase spending on refugee affairs. But offering interpretation services is essential to improving the immigration system. Higher compensation could be one option to address the current shortage of interpreters," said Lee Hyun-seo, a lawyer at the Yoon & Yang Pro Bono Foundation.

By Choi Jae-hee (cjh@heraldcorp.com)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)